After 7 years living in Chester I have finally gotten around to visiting the cathedral, actually it took a parental visit to get me over the threshold! It was a cold frosty morning in January when we visited.

I am an atheist, but culturally a Christian one, so in a sense I feel at home. I tend to see cathedrals as medieval moon-shots – endeavours of almost unbelievable scale for the time in which they were constructed. We approached the cathedral from the North, along the city walls. Passing along Abbey Street where we saw this rather skewed gateway:

Charles Kingsley, author of “The Water Babies”, was canon at the cathedral and also founder of the Chester Natural Sciences Society. I will spare you the photo of the blue plaque from which I gleaned this information. On the way into the cathedral, the Cloisters.

You’ll have to forgive me, I’m not too up on the nomenclature for ecclesiastical architectural features, here I am looking down the nave at the altar screen (probably). I’m having problems because of the large variations in light intensity within the scene. There is also some evidence for my problem of always taking photos at a tilt:

A detail in the roof of the nave:

Off the nave is the Consistory Court, this is the Apparitor’s Chair, or maybe it isn’t the information board hedged slightly on this point. The woodwork in the Consistory Court dates from the early 17th century.

This fabulous device is a Gurney Warm Air Stove, installed in the late 19th century. Sir Goldsworthy Gurney, the inventor of the stove, was an interesting chap.

Chester Cathedral was built in stages, based on a monastic Norman church built in 1093, there are some traces of this original building in the North Transept:

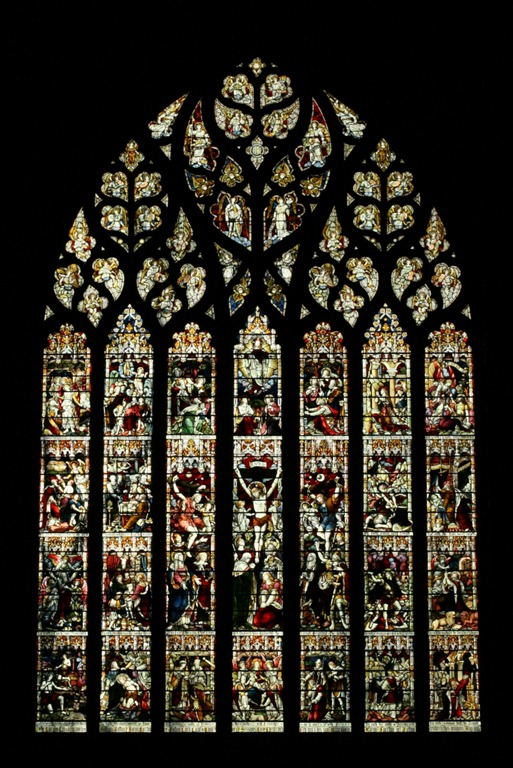

You can’t go to a cathedral without trying to photograph a stained-glass window:

The Choir Stalls, fantastically ornate and clearly difficult to dust:

Frustrated at trying to take photos of difficult to photo things, I thought I’d try something easier: the floor tiles:

That went well, I’ll do some more!

A detail of the ceiling in the the East Nave:

Stone detail in the Cloisters:

Out into the Cloister gardens where there is this fine sculpture by Stephen Broadbent, from here we could hear the croaking of what sounded like ravens, however the little tinkers remained hidden in the heights of the cathedral tower so it was difficult to be sure:

I found cathedral photography rather challenging, the problems are that it’s dark and where it isn’t dark it’s very bright! The human eye-brain combination is terribly clever, it seamlessly accounts for enormous variations in brightness without any great degradation in the user experience. As a photographer this all becomes very obvious. There are workarounds: you can provide your own lighting or you can ramp up the sensitivity of your virtual film (increasing the ISO number), use a tripod (if that’s permitted) to allow longer exposure times, and take multiple shots at different exposures melding them into one shot (known as high dynamic range (HDR) imaging).

High dynamic range imaging and display are hot research areas. The problem on the display side is that if you display a picture of a bright window with a dark surround, even an HDR image, then the surround will “look” too dark. What you need to do is vary the brightness of pixels according to their surrounding pixels – it’s called “tone mapping”, precisely what algorithm you should use to do this is the subject of research.

Most of these shots were taken with my new Canon 50mm f/1.4 although a couple were done with the Canon 28-135mm. Next time I think I’ll try out my ultrawide angle lens: 10-22mm, handy for those smaller corners and perhaps a bit less prone to blur.