Another result of my plea for reading suggestions on twitter; this is a review and summary of Arthur Koestler’s book “The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man’s Changing Vision of the Universe”. The book is a history of cosmology running from Pythagoras, in the 6th century BC, to Galileo who spanned the end of the 16th century, just touching lightly on Newton. It traces a revolution from a time when the cosmos, beyond the earth, was considered different, stable and perfect, to a time when it was shown to be subject to earthly physics, be changeable and not perfect by any reasonable definition.

Another result of my plea for reading suggestions on twitter; this is a review and summary of Arthur Koestler’s book “The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man’s Changing Vision of the Universe”. The book is a history of cosmology running from Pythagoras, in the 6th century BC, to Galileo who spanned the end of the 16th century, just touching lightly on Newton. It traces a revolution from a time when the cosmos, beyond the earth, was considered different, stable and perfect, to a time when it was shown to be subject to earthly physics, be changeable and not perfect by any reasonable definition.

Kuhn’s language of paradigm shifts seems rather overused to me but here is an example of a true paradigm shift. The sleepwalkers in the title refers to the idea that the protagonists didn’t really know where they were headed with their ideas and quite often were lucky with errors which cancelled each other out.

The book starts with a cursory look at Babylonian and early Greek astronomy; despite considerable observational acumen their models of the universe were outright mythical. The Pythagoranean Brotherhood although in many senses still mystical started to think about the physics of the universe. I have a tendency to think of the ancient Greeks as one blob but as the book makes clear there is a huge span of time, and outlook, between Pythagoras, Aristotle and Plato and Ptolemy. Koestler is quite clearly disappointed with the Greeks: they make a promising start with Pythagoras, Aristarchus developed a heliocentric model for the solar system and then with Plato, Aristotle and Ptolemy they regress back to a geocentric model.

Following on from the Greeks the Middle Ages are covered, James Hannam in his book “God’s Philosophers” has covered why this period wasn’t all that bad in terms of intellectual development. Koestler is less sympathetic, his key accusations are that they philosophers of the middle ages were in thrall to the later Greeks and furthermore there were elements of Christian theology that abjured the pleasure of knowledge for knowledge’s sake.

After these preliminaries, Koestler turns to the core of his work: the cosmological developments of Copernicus, Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei.

The model of the universe handed down from the ancient Greeks was one of circles (often referred to in this context as epicycles), they believed that motion in a circle was perfect, that the heavens were a separate, perfect realm and that therefore all motion in the heavens must be based on circular motion. Further, the model dominating at the end of their period, held that the earth lay at the centre of these circular motions. The only problem with this model is that it doesn’t fit well the observed motions of the sun, moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn – the observable solar system which lay against an unchanging starry background. Or rather you can get a rough fit at the expense of stacking together a great number of epicycles – something like 50.

Copernicus’ contribution, published on his death in 1543, was to put the sun back at the centre of the universe. Copernicus led a rather uneventful life, was no sort of astronomical observer and only published his thesis at the end of his life at the strong urging of Georg Joachim Rheticus. He’d discussed his model fairly freely during his life, and his reasons for not publishing were more to do with fear of ridicule from his contemporaries rather than theological pressure. After his death his work, with the exception of the astronomical tables, sank into obscurity partly because it was a difficult read and partly because he managed to ostracise his former cheerleader, Rheticus. Copernicus’ model still holds to the epicycles of the Greeks, and only marginally reduces the complexity of the model.

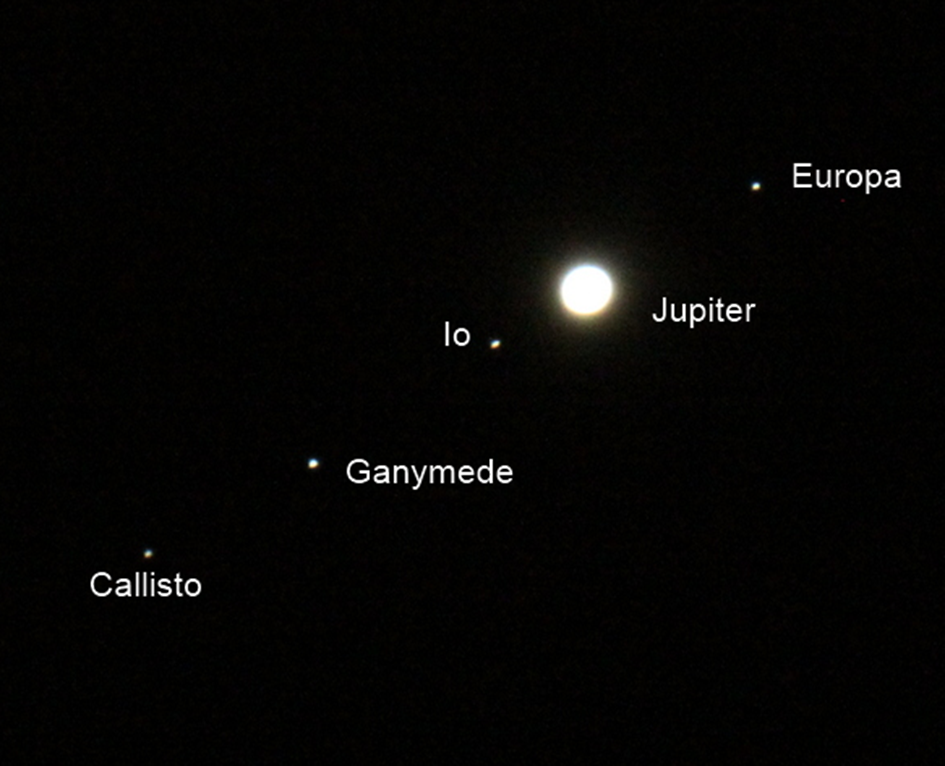

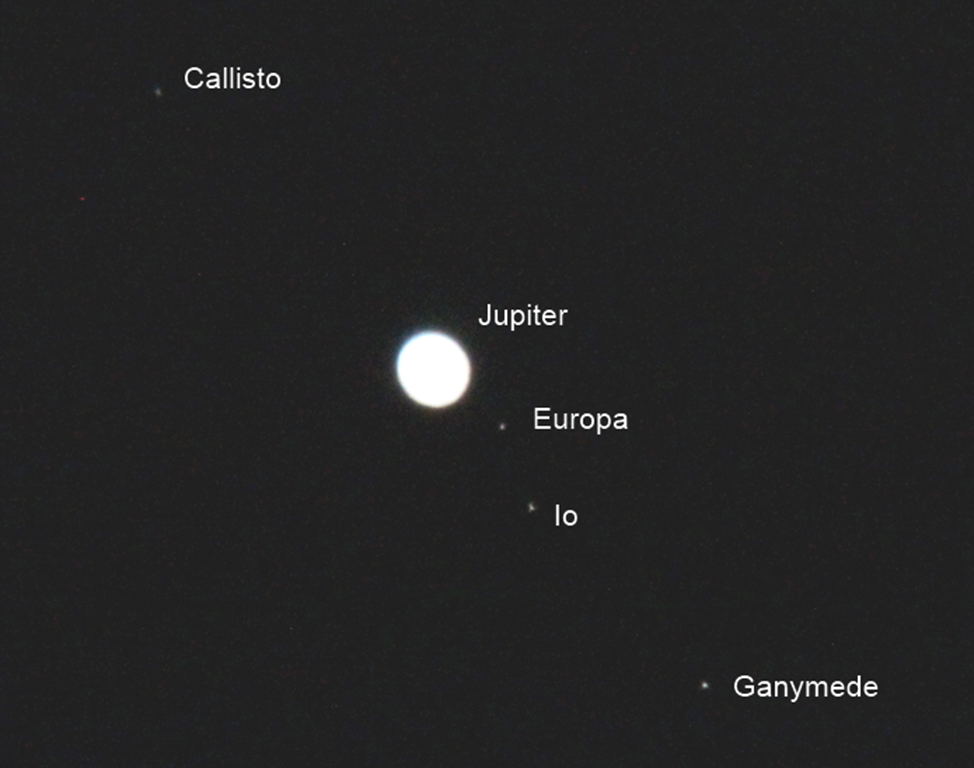

Next up comes Johannes Kepler, interspersed with Tycho Brahe. Brahe was an astronomical observer and nobleman, funded very well by the Danish king; given his own island Hveen where he built his observatory. As a keen astrologer he began his observation programme when he found a conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn was poorly predicted by current astronomical tables – how can you cast an accurate fortune under these circumstances?

Kepler was a theoretician rather than an observer but also a keen astrologer. I emphasise this because these days astrology is not held in high regard but it is the father of observational astronomy. He had started to develop a model of the solar system based on the Platonic solids – something of a mystical exercise but realised he needed better data to support his model. Brahe was the man with the data, Kepler was only just in time though – he travelled to work with Brahe when Brahe moved to Prague less than 2 years later Brahe was dead. Nowadays we know Kepler for his three laws of planetary motion – it’s worth noting that Kepler’s laws are labelled retrospectively.)

He left copious records of his progress which Koestler traces in great detail, Kepler’s struggle to recognise that planetary orbits were ellipses was heroic and has something of a pantomime air to it – “They’re right in front of you!”. His approach was unprecedented in the sense that he sought to accurately model the very best, most recent measurements. Kepler also made some attempts at a physical model to describe the motions but ultimately he is remembered for the detailed description of their motion. Since it is not central to his theme, Koestler makes only passing reference to Kepler’s work on optics.

The penultimate figure in the story is Galileo, despite Kepler’s best efforts Galileo pretty much ignored him. Galileo gets quite short shrift from Koestler who feels that he brought his troubles with the Catholic Church upon himself. Reading this account his position is not unreasonable. Galileo’s two big contributions to the story are his promotion and use of the telescope, and his work on the motion of terrestrial bodies, the generalisation of which and application to the solar system was Newton’s great triumph. Cosmologically he was only later in his life a supporter of the somewhat retro Copernican model which was a cul-de-sac in terms of theoretical developments. At the time the Catholic Church, particularly the Jesuits, were interested in astronomy and not particularly hardline about the interpretation of Scripture to fit observations. Galileo wound them up both by claiming all newly observed celestial phenomena as his own and by putting the words of the Pope in the mouth of an idiot in one of his Dialogues.

This highlights two of the wider themes that Koestler brings to his book. At one point he describes his cast of characters as “moral dwarves”, he states this is relative to their scientific achievements but returns to this theme in the epilogue where he feels that our scientific developments have not been matched by our spiritual development. The second is the schism between science and the Church that began in this period, Koestler seems to put much of the blame for this on Galileo’s head feeling that it is by no means inevitable. In the epilogue he also draws a comparison between biological evolution and scientific developments, highlighting specifically that there are long periods of not that much happening and many diversions from the “true” path.

The book finishes with a brief mention of Newton’s synthesis of Kepler’s laws and Galileo’s dynamics to produce a model of the solar system which is close to that which we hold today.

This really is a rollicking good read! This is a relatively old book, published in 1959 and one might anticipate that it has not fully caught up with modern historiography however a brief look around the internet suggests that he is not criticised in any great sense. Koestler does tend to focus on a limited number of “great” individuals and goes for “firsts” but this perhaps is what makes it a good read.

Footnotes

My Evernotes for the book are here, last page of the book at the top!