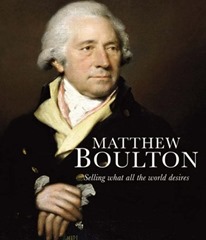

Matthew Boulton: Selling what all the World Desires by Shena Mason is a rather sumptuous book featuring a collection of articles and a catalogue of objects relating to Matthew Boulton, organised by Birmingham City Council on the bicentenary of his death in 2009.

Matthew Boulton: Selling what all the World Desires by Shena Mason is a rather sumptuous book featuring a collection of articles and a catalogue of objects relating to Matthew Boulton, organised by Birmingham City Council on the bicentenary of his death in 2009.

Boulton was famous for his Soho Manufactory built a couple of miles from the centre of modern Birmingham. There he started making “toys”, following in the footsteps of his father. At the time “toys” were small metal objects such as buttons, buckles, watch chains and the like for which Birmingham was famous. Over time he brought a high degree of mechanisation and productionisation to the process.

But “toys” were only the start of his business interests, he soon moved into making higher value objects such as vases, candle holders and tableware made from silver, Sheffield plate (silver plated tin) and ormolu (gold gilded bronze or brass), aiming to supply a growing middle class clientele by producing objects at scale with a high degree of mechanisation to reduce cost. For this he cultivated connections in well-to-do society, and employed the best designers.

I was interested to read the article on Picturing Soho by Val Loggie which talks about how the architected design of the factory was essentially part of Boulton’s marketing strategy. The Soho site drew many visitors, it was a feature of the late Enlightenment that facilities such as these attracted visitors from across Europe and America. Boulton even installed tea rooms and a show room to furnish their needs. Although a continuing concern was the risk of industrial espionage which led ultimately to the curtailment of such visits in the early years of the 19th century.

As part of his silver work he campaigned for Birmingham to have its own Assay Office to hallmark silver goods. Previously silver items needed to go to Chester to be assayed and receive a hallmark which was a lengthy journey, costing money and risking damage to items. Gaining an assay office required an act of parliament for which Boulton lobbied in the face of opposition from London silver and goldsmiths. The London case was damaged when a “secret shopper” investigation showed that most silverware passing through the London assay office was below standard, and furthermore they were caught trying to bribe Boulton’s former employees to speak against him. An assay office was granted to Sheffield in the same act.

Boulton also built a mint at Soho, pretty much fully mechanising the process of producing coinage, trade tokens and decorative medals. This work seems to have been one of his more profitable enterprises. Towards the end of the 18th century the government had not minted new copper coinage for quite some time which caused problems because it was often pennies and tuppences that workers needed to buy essentials. Ultimately Boulton was given the contract to mint a large quantity of copper coinage, and was selling minting machinery around the world.

Finally, there was his work on steam engines with James Watt. Watt invented an improvement to the Newcomen steam engine in use at the time which made it much more efficient, in terms of the amount of coal required to produce the same power. Watt also developed engines that produced reliable rotary motion, essentially for driving factory machinery rather than just pumping water out of mines. In the first instance Watt and Boulton acted as consultants, designing engines for specific customers and buying in parts from various suppliers to construct them. They charged a fraction of the cost saving from reduced coal use, which sounds like it was rather difficult to administer. The engine business, they maintained their income by lobbying parliament to extend their patent. Later they built a foundry at Soho which made all of the parts of the engine.

Actually, there was one more thing, Watt and Boulton produced a system for mechanical reproduction of letters and paintings.

Boulton’s businesses were continued after his death by his son, and the son of the James Watt. The silver plate company and foundry lasted longest but by the end of the 19th century they were gone. The Soho Manufactory made it to the dawn of photography but was demolished in 1863. Boulton’s Soho House remains on the site but the rest of the works, and parkland in which they sat have been overtaken by housing.

In some ways he was the metalworking equivalent of Josiah Wedgewood with whom he was well-acquainted through there membership of The Lunar Society, you can read more about them in Jenny Uglow’s The Lunar Men. He was also interested in the science of the time.

Many of Boulton’s ventures seem to have been of limited commercial value, they often required significant investment which he raised via loans, and revenue typically fell below expectations.

This is a beautiful book, the articles cover the key parts of Boulton’s work at Soho but it is not a biography. The catalogue, which makes up half the book is worth reading too – the photographs are gorgeous and there are descriptive text boxes which explain the wider context of the objects.

1 comments

Greeks, Egyptians, Aztecs and Mayans rolled bones – the original version of dice – for entertainment and divination. Again,

there are often restrictions, so read rigorously. Usually the

cards that specialists . handle. http://www.ndxa.net/modules/wordpress/wp-ktai.php?view=redir&url=http%3A%2F%2Flpe88.life%2Findex.php%2Fother-games%2Fntc33