Author's posts

May 08 2015

A cockroach emerges…

I’m a Liberal Democrat. Our party president, Tim Farron, once described us being like cockroaches in our indestructability.

Today the Liberal Democrat parliamentary party has dropped from 57 parliamentary seats to 8, slightly lower than was achieved by the Liberal Party in 1979. Since 2010 Liberal Democrat local councillors have experienced this level of defeat, as have the party’s Members in the European Parliament. It looked like things might be different for the parliamentary party, but they weren’t.

The writing was on the wall from the moment Nick Clegg and David Cameron stepped into the Downing Street rose garden in May 2010. Our opinion poll ratings plummeted from that moment, before we’d done anything else but form the Coalition.

Today, in May 2015 we lost seats to Labour because of the “Great Betrayal”, we lost seats to the Tories because people thought of the Coalition “I actually quite like this government” and then backed the lead partner, we lost votes to UKIP and the Greens because they are the new repository of the protest vote, we lost seats to the SNP because nationalism trumps all.

The night had virtually no redeeming features. I particularly feel the loss of MPs like Lynne Featherstone, Jo Swinson and Julian Huppert all of whom made significant contributions in parliament on equality, science and anti-authoritarianism. All of whom appeared to be popular local MPs, all of whom were swept aside by the national tide.

Nick Clegg retained his seat, for which I’m rather pleased. Outsiders don’t realise quite how dependent a Lib Dem leader is on their party. The things Nick Clegg took the blame for were the things we as Liberal Democrats had collectively decided. He has been the one that has born the brunt of outrage against the Liberal Democrats with good grace. He is the one, more than any of the three main party leaders, who has talked with the public.

The political landscape won’t remould itself, it won’t be remoulded by online petitions. It won’t be remoulded by the “progressive alliance” engaging in rounds of recrimination. It won’t be remoulded by endless venting on twitter, or invoking the apocalypse. It won’t be remoulded by the lion’s roar, or an idiot with a pair of trews.

It will be remoulded by people like me who spend their spare time doing local politics: sitting in interminable meetings in their evenings, posting leaflets through doors, standing for local elections, helping local people and breaking out once every 5 years or so to fight a General Election.

I’m still a Liberal Democrat. I’m proud of what we achieved in coalition in the last 5 years, it’s been the best time to be a Liberal Democrat since I joined the party in 1988.

I’m going to go back to trying to win seats at elections and making sure the liberal voice is heard.

May 07 2015

General Election 2015–expected declaration times

There is a General Election being held in the UK today, along with local council elections in some parts of the country. The count will take place commencing at 10pm this evening, and the count will likely finish sometime around noon tomorrow.

Should you stay up awaiting all the results?

My advice is “no” but that’s because I’m getting old and like my sleep! My plan is to stay up for the BBC exit poll at 10:15pm and then go to bed, probably to awake with the dawn chorus at 4am.

If you do stay up then what can you expect? The Press Association list of estimated declaration times from here, they’re based on council estimates and previous declarations where the council provides no estimates. My experience is that the more interesting results are delayed beyond their estimated time.

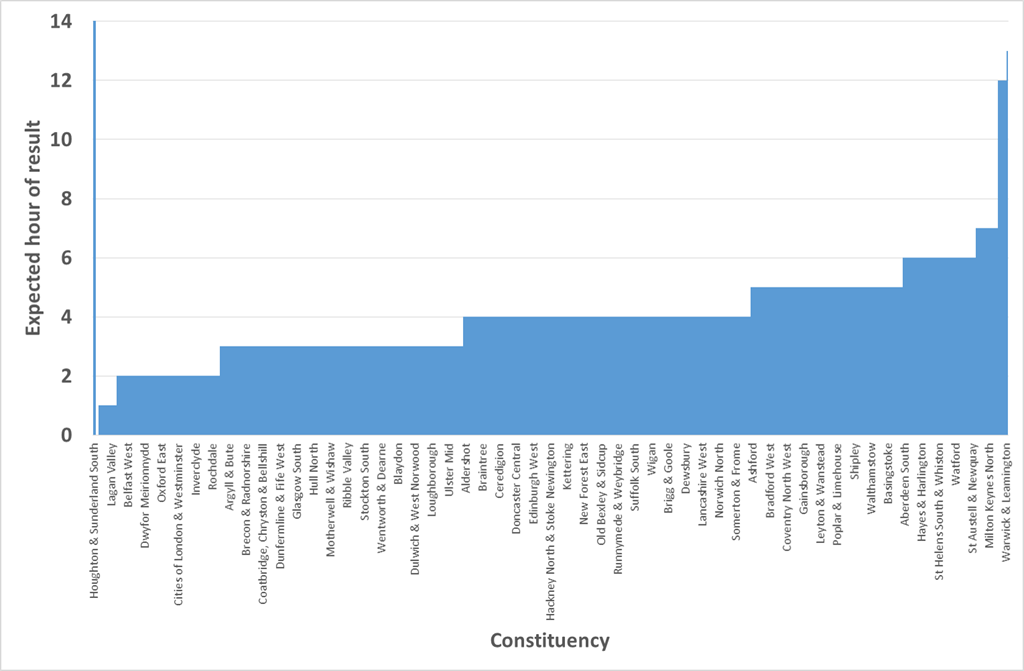

As you can see from the chart below, aside from a scattering of seats, things start to pick up around 2am. Results start to pour in around 3am and by 7am it is all over bar a few stragglers.

If you want a more narrative description of what will happen and some anticipated milestones then The Guardian has a report (here).

For the record, and for readability here is the complete list:

| 320 | Houghton & Sunderland South | 23:00 |

| 603 | Washington & Sunderland West | 23:30 |

| 551 | Sunderland Central | 00:01 |

| 216 | Durham North West | 00:30 |

| 14 | Antrim North | 01:00 |

| 175 | Dagenham & Rainham | 01:00 |

| 215 | Durham North | 01:00 |

| 255 | Foyle | 01:00 |

| 435 | Nuneaton | 01:00 |

| 176 | Darlington | 01:30 |

| 214 | Durham, City of | 01:30 |

| 221 | Easington | 01:30 |

| 347 | Lagan Valley | 01:30 |

| 407 | Na h-Eileanan an Iar | 01:30 |

| 584 | Tyrone West | 01:30 |

| 586 | Upper Bann | 01:30 |

| 588 | Vale of Clwyd | 01:30 |

| 12 | Angus | 02:00 |

| 13 | Antrim East | 02:00 |

| 28 | Barking | 02:00 |

| 38 | Battersea | 02:00 |

| 45 | Belfast East | 02:00 |

| 46 | Belfast North | 02:00 |

| 47 | Belfast South | 02:00 |

| 48 | Belfast West | 02:00 |

| 66 | Bishop Auckland | 02:00 |

| 71 | Blaenau Gwent | 02:00 |

| 106 | Broxbourne | 02:00 |

| 125 | Canterbury | 02:00 |

| 131 | Carmarthen East & Dinefwr | 02:00 |

| 132 | Carmarthen West & Pembrokeshire South | 02:00 |

| 134 | Castle Point | 02:00 |

| 139 | Chelmsford | 02:00 |

| 142 | Chesham & Amersham | 02:00 |

| 150 | Christchurch | 02:00 |

| 202 | Down North | 02:00 |

| 217 | Dwyfor Meirionnydd | 02:00 |

| 223 | East Kilbride, Strathaven & Lesmahagow | 02:00 |

| 226 | Eastleigh | 02:00 |

| 239 | Epping Forest | 02:00 |

| 250 | Fife North East | 02:00 |

| 269 | Glenrothes | 02:00 |

| 285 | Halton | 02:00 |

| 345 | Kirkcaldy & Cowdenbeath | 02:00 |

| 348 | Lanark & Hamilton East | 02:00 |

| 375 | Llanelli | 02:00 |

| 427 | Northampton North | 02:00 |

| 428 | Northampton South | 02:00 |

| 443 | Oxford East | 02:00 |

| 462 | Putney | 02:00 |

| 487 | Rutherglen & Hamilton West | 02:00 |

| 530 | Staffordshire South | 02:00 |

| 542 | Strangford | 02:00 |

| 552 | Surrey East | 02:00 |

| 562 | Tamworth | 02:00 |

| 574 | Tooting | 02:00 |

| 647 | Ynys Mon | 02:00 |

| 570 | Thornbury & Yate | 02:15 |

| 15 | Antrim South | 02:30 |

| 143 | Chester, City of | 02:30 |

| 151 | Cities of London & Westminster | 02:30 |

| 153 | Cleethorpes | 02:30 |

| 189 | Devon East | 02:30 |

| 211 | Dundee East | 02:30 |

| 212 | Dundee West | 02:30 |

| 227 | Eddisbury | 02:30 |

| 234 | Ellesmere Port & Neston | 02:30 |

| 251 | Filton & Bradley Stoke | 02:30 |

| 287 | Hampshire East | 02:30 |

| 296 | Hartlepool | 02:30 |

| 302 | Hemel Hempstead | 02:30 |

| 308 | Hertford & Stortford | 02:30 |

| 330 | Inverclyde | 02:30 |

| 334 | Islington North | 02:30 |

| 335 | Islington South & Finsbury | 02:30 |

| 342 | Kilmarnock & Loudoun | 02:30 |

| 344 | Kingswood | 02:30 |

| 359 | Leicestershire North West | 02:30 |

| 367 | Lichfield | 02:30 |

| 379 | Ludlow | 02:30 |

| 385 | Makerfield | 02:30 |

| 399 | Mitcham & Morden | 02:30 |

| 402 | Montgomeryshire | 02:30 |

| 412 | Newbury | 02:30 |

| 474 | Rochdale | 02:30 |

| 533 | Stirling | 02:30 |

| 615 | Westminster North | 02:30 |

| 621 | Wimbledon | 02:30 |

| 636 | Workington | 02:30 |

| 646 | Yeovil | 02:30 |

| 1 | Aberavon | 03:00 |

| 2 | Aberconwy | 03:00 |

| 6 | Airdrie & Shotts | 03:00 |

| 10 | Alyn & Deeside | 03:00 |

| 11 | Amber Valley | 03:00 |

| 16 | Arfon | 03:00 |

| 17 | Argyll & Bute | 03:00 |

| 29 | Barnsley Central | 03:00 |

| 30 | Barnsley East | 03:00 |

| 33 | Basildon South & Thurrock East | 03:00 |

| 41 | Bedford | 03:00 |

| 49 | Bermondsey & Old Southwark | 03:00 |

| 75 | Bolsover | 03:00 |

| 76 | Bolton North East | 03:00 |

| 77 | Bolton South East | 03:00 |

| 78 | Bolton West | 03:00 |

| 81 | Bosworth | 03:00 |

| 84 | Bracknell | 03:00 |

| 89 | Brecon & Radnorshire | 03:00 |

| 90 | Brent Central | 03:00 |

| 91 | Brent North | 03:00 |

| 100 | Bristol North West | 03:00 |

| 102 | Bristol West | 03:00 |

| 111 | Bury North | 03:00 |

| 112 | Bury South | 03:00 |

| 113 | Bury St Edmunds | 03:00 |

| 117 | Camberwell & Peckham | 03:00 |

| 130 | Carlisle | 03:00 |

| 154 | Clwyd South | 03:00 |

| 155 | Clwyd West | 03:00 |

| 156 | Coatbridge, Chryston & Bellshill | 03:00 |

| 160 | Copeland | 03:00 |

| 170 | Croydon Central | 03:00 |

| 171 | Croydon North | 03:00 |

| 172 | Croydon South | 03:00 |

| 179 | Delyn | 03:00 |

| 181 | Derby North | 03:00 |

| 182 | Derby South | 03:00 |

| 184 | Derbyshire Mid | 03:00 |

| 185 | Derbyshire North East | 03:00 |

| 186 | Derbyshire South | 03:00 |

| 209 | Dunbartonshire East | 03:00 |

| 213 | Dunfermline & Fife West | 03:00 |

| 224 | East Lothian | 03:00 |

| 241 | Erewash | 03:00 |

| 244 | Exeter | 03:00 |

| 245 | Falkirk | 03:00 |

| 256 | Fylde | 03:00 |

| 260 | Gedling | 03:00 |

| 262 | Glasgow Central | 03:00 |

| 263 | Glasgow East | 03:00 |

| 264 | Glasgow North | 03:00 |

| 265 | Glasgow North East | 03:00 |

| 266 | Glasgow North West | 03:00 |

| 267 | Glasgow South | 03:00 |

| 268 | Glasgow South West | 03:00 |

| 273 | Gower | 03:00 |

| 290 | Hampstead & Kilburn | 03:00 |

| 293 | Harrogate & Knaresborough | 03:00 |

| 298 | Hastings & Rye | 03:00 |

| 299 | Havant | 03:00 |

| 310 | Hertfordshire South West | 03:00 |

| 314 | High Peak | 03:00 |

| 316 | Holborn & St Pancras | 03:00 |

| 318 | Hornsey & Wood Green | 03:00 |

| 323 | Hull East | 03:00 |

| 324 | Hull North | 03:00 |

| 325 | Hull West & Hessle | 03:00 |

| 326 | Huntingdon | 03:00 |

| 333 | Isle of Wight | 03:00 |

| 337 | Jarrow | 03:00 |

| 343 | Kingston & Surbiton | 03:00 |

| 346 | Knowsley | 03:00 |

| 376 | Londonderry East | 03:00 |

| 386 | Maldon | 03:00 |

| 393 | Merthyr Tydfil & Rhymney | 03:00 |

| 395 | Middlesbrough South & Cleveland East | 03:00 |

| 403 | Moray | 03:00 |

| 406 | Motherwell & Wishaw | 03:00 |

| 408 | Neath | 03:00 |

| 417 | Newport East | 03:00 |

| 418 | Newport West | 03:00 |

| 421 | Norfolk Mid | 03:00 |

| 436 | Ochil & Perthshire South | 03:00 |

| 445 | Paisley & Renfrewshire North | 03:00 |

| 446 | Paisley & Renfrewshire South | 03:00 |

| 450 | Perth & Perthshire North | 03:00 |

| 451 | Peterborough | 03:00 |

| 460 | Preston | 03:00 |

| 469 | Renfrewshire East | 03:00 |

| 471 | Ribble Valley | 03:00 |

| 481 | Rother Valley | 03:00 |

| 482 | Rotherham | 03:00 |

| 486 | Rushcliffe | 03:00 |

| 513 | Skipton & Ripon | 03:00 |

| 514 | Sleaford & North Hykeham | 03:00 |

| 515 | Slough | 03:00 |

| 516 | Solihull | 03:00 |

| 517 | Somerset North | 03:00 |

| 522 | South Shields | 03:00 |

| 528 | Stafford | 03:00 |

| 535 | Stockton North | 03:00 |

| 536 | Stockton South | 03:00 |

| 540 | Stone | 03:00 |

| 550 | Suffolk West | 03:00 |

| 558 | Swansea East | 03:00 |

| 559 | Swansea West | 03:00 |

| 560 | Swindon North | 03:00 |

| 561 | Swindon South | 03:00 |

| 565 | Telford | 03:00 |

| 571 | Thurrock | 03:00 |

| 589 | Vale of Glamorgan | 03:00 |

| 608 | Wellingborough | 03:00 |

| 610 | Welwyn Hatfield | 03:00 |

| 611 | Wentworth & Dearne | 03:00 |

| 623 | Windsor | 03:00 |

| 641 | Wrexham | 03:00 |

| 642 | Wycombe | 03:00 |

| 643 | Wyre & Preston North | 03:00 |

| 8 | Aldridge-Brownhills | 03:30 |

| 35 | Bassetlaw | 03:30 |

| 40 | Beckenham | 03:30 |

| 42 | Bedfordshire Mid | 03:30 |

| 44 | Bedfordshire South West | 03:30 |

| 69 | Blackpool North & Cleveleys | 03:30 |

| 70 | Blackpool South | 03:30 |

| 72 | Blaydon | 03:30 |

| 82 | Bournemouth East | 03:30 |

| 83 | Bournemouth West | 03:30 |

| 104 | Bromley & Chislehurst | 03:30 |

| 109 | Burnley | 03:30 |

| 121 | Cambridgeshire North West | 03:30 |

| 122 | Cambridgeshire South | 03:30 |

| 136 | Charnwood | 03:30 |

| 141 | Cheltenham | 03:30 |

| 164 | Cotswolds, The | 03:30 |

| 201 | Dover | 03:30 |

| 203 | Down South | 03:30 |

| 206 | Dulwich & West Norwood | 03:30 |

| 210 | Dunbartonshire West | 03:30 |

| 222 | East Ham | 03:30 |

| 233 | Edmonton | 03:30 |

| 237 | Enfield North | 03:30 |

| 238 | Enfield Southgate | 03:30 |

| 272 | Gosport | 03:30 |

| 276 | Great Grimsby | 03:30 |

| 292 | Harlow | 03:30 |

| 368 | Lincoln | 03:30 |

| 369 | Linlithgow & Falkirk East | 03:30 |

| 374 | Livingston | 03:30 |

| 377 | Loughborough | 03:30 |

| 396 | Midlothian | 03:30 |

| 419 | Newry & Armagh | 03:30 |

| 442 | Orpington | 03:30 |

| 463 | Rayleigh & Wickford | 03:30 |

| 468 | Reigate | 03:30 |

| 521 | South Ribble | 03:30 |

| 544 | Streatham | 03:30 |

| 548 | Suffolk Coastal | 03:30 |

| 553 | Surrey Heath | 03:30 |

| 569 | Thirsk & Malton | 03:30 |

| 576 | Torfaen | 03:30 |

| 585 | Ulster Mid | 03:30 |

| 590 | Vauxhall | 03:30 |

| 593 | Walsall North | 03:30 |

| 594 | Walsall South | 03:30 |

| 598 | Warley | 03:30 |

| 607 | Weaver Vale | 03:30 |

| 612 | West Bromwich East | 03:30 |

| 613 | West Bromwich West | 03:30 |

| 614 | West Ham | 03:30 |

| 634 | Worcestershire Mid | 03:30 |

| 640 | Wrekin, The | 03:30 |

| 5 | Aberdeenshire West & Kincardine | 04:00 |

| 7 | Aldershot | 04:00 |

| 19 | Ashfield | 04:00 |

| 23 | Ayr, Carrick & Cumnock | 04:00 |

| 24 | Ayrshire Central | 04:00 |

| 25 | Ayrshire North & Arran | 04:00 |

| 27 | Banff & Buchan | 04:00 |

| 31 | Barrow & Furness | 04:00 |

| 32 | Basildon & Billericay | 04:00 |

| 43 | Bedfordshire North East | 04:00 |

| 55 | Bexleyheath & Crayford | 04:00 |

| 61 | Birmingham Ladywood | 04:00 |

| 67 | Blackburn | 04:00 |

| 88 | Braintree | 04:00 |

| 93 | Brentwood & Ongar | 04:00 |

| 94 | Bridgend | 04:00 |

| 95 | Bridgwater & Somerset West | 04:00 |

| 99 | Bristol East | 04:00 |

| 101 | Bristol South | 04:00 |

| 105 | Bromsgrove | 04:00 |

| 107 | Broxtowe | 04:00 |

| 114 | Caerphilly | 04:00 |

| 120 | Cambridgeshire North East | 04:00 |

| 124 | Cannock Chase | 04:00 |

| 133 | Carshalton & Wallington | 04:00 |

| 135 | Ceredigion | 04:00 |

| 140 | Chelsea & Fulham | 04:00 |

| 144 | Chesterfield | 04:00 |

| 145 | Chichester | 04:00 |

| 168 | Crawley | 04:00 |

| 173 | Cumbernauld, Kilsyth & Kirkintilloch East | 04:00 |

| 177 | Dartford | 04:00 |

| 183 | Derbyshire Dales | 04:00 |

| 190 | Devon North | 04:00 |

| 191 | Devon South West | 04:00 |

| 192 | Devon West & Torridge | 04:00 |

| 194 | Don Valley | 04:00 |

| 195 | Doncaster Central | 04:00 |

| 196 | Doncaster North | 04:00 |

| 200 | Dorset West | 04:00 |

| 204 | Dudley North | 04:00 |

| 205 | Dudley South | 04:00 |

| 207 | Dumfries & Galloway | 04:00 |

| 208 | Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale & Tweeddale | 04:00 |

| 225 | Eastbourne | 04:00 |

| 228 | Edinburgh East | 04:00 |

| 229 | Edinburgh North & Leith | 04:00 |

| 230 | Edinburgh South | 04:00 |

| 231 | Edinburgh South West | 04:00 |

| 232 | Edinburgh West | 04:00 |

| 236 | Eltham | 04:00 |

| 240 | Epsom & Ewell | 04:00 |

| 242 | Erith & Thamesmead | 04:00 |

| 243 | Esher & Walton | 04:00 |

| 246 | Fareham | 04:00 |

| 253 | Folkestone & Hythe | 04:00 |

| 258 | Garston & Halewood | 04:00 |

| 259 | Gateshead | 04:00 |

| 270 | Gloucester | 04:00 |

| 278 | Greenwich & Woolwich | 04:00 |

| 279 | Guildford | 04:00 |

| 280 | Hackney North & Stoke Newington | 04:00 |

| 281 | Hackney South & Shoreditch | 04:00 |

| 286 | Hammersmith | 04:00 |

| 289 | Hampshire North West | 04:00 |

| 291 | Harborough | 04:00 |

| 294 | Harrow East | 04:00 |

| 295 | Harrow West | 04:00 |

| 306 | Hereford & Herefordshire South | 04:00 |

| 311 | Hertsmere | 04:00 |

| 313 | Heywood & Middleton | 04:00 |

| 332 | Ipswich | 04:00 |

| 336 | Islwyn | 04:00 |

| 341 | Kettering | 04:00 |

| 361 | Leigh | 04:00 |

| 362 | Lewes | 04:00 |

| 363 | Lewisham Deptford | 04:00 |

| 364 | Lewisham East | 04:00 |

| 365 | Lewisham West & Penge | 04:00 |

| 380 | Luton North | 04:00 |

| 381 | Luton South | 04:00 |

| 383 | Maidenhead | 04:00 |

| 390 | Mansfield | 04:00 |

| 392 | Meriden | 04:00 |

| 401 | Monmouth | 04:00 |

| 409 | New Forest East | 04:00 |

| 411 | Newark | 04:00 |

| 413 | Newcastle-under-Lyme | 04:00 |

| 414 | Newcastle upon Tyne Central | 04:00 |

| 415 | Newcastle upon Tyne East | 04:00 |

| 416 | Newcastle upon Tyne North | 04:00 |

| 422 | Norfolk North | 04:00 |

| 429 | Northamptonshire South | 04:00 |

| 432 | Nottingham East | 04:00 |

| 433 | Nottingham North | 04:00 |

| 434 | Nottingham South | 04:00 |

| 437 | Ogmore | 04:00 |

| 438 | Old Bexley & Sidcup | 04:00 |

| 441 | Orkney & Shetland | 04:00 |

| 447 | Pendle | 04:00 |

| 448 | Penistone & Stocksbridge | 04:00 |

| 449 | Penrith & The Border | 04:00 |

| 452 | Plymouth Moor View | 04:00 |

| 453 | Plymouth Sutton & Devonport | 04:00 |

| 459 | Preseli Pembrokeshire | 04:00 |

| 467 | Redditch | 04:00 |

| 473 | Richmond Park | 04:00 |

| 476 | Rochford & Southend East | 04:00 |

| 478 | Romsey & Southampton North | 04:00 |

| 485 | Runnymede & Weybridge | 04:00 |

| 489 | Saffron Walden | 04:00 |

| 497 | Scarborough & Whitby | 04:00 |

| 501 | Selby & Ainsty | 04:00 |

| 502 | Sevenoaks | 04:00 |

| 523 | Southampton Itchen | 04:00 |

| 524 | Southampton Test | 04:00 |

| 525 | Southend West | 04:00 |

| 527 | Spelthorne | 04:00 |

| 529 | Staffordshire Moorlands | 04:00 |

| 546 | Stroud | 04:00 |

| 547 | Suffolk Central & Ipswich North | 04:00 |

| 549 | Suffolk South | 04:00 |

| 554 | Surrey South West | 04:00 |

| 555 | Sussex Mid | 04:00 |

| 556 | Sutton & Cheam | 04:00 |

| 557 | Sutton Coldfield | 04:00 |

| 578 | Tottenham | 04:00 |

| 580 | Tunbridge Wells | 04:00 |

| 581 | Twickenham | 04:00 |

| 602 | Warwickshire North | 04:00 |

| 606 | Wealden | 04:00 |

| 616 | Westmorland & Lonsdale | 04:00 |

| 617 | Weston-Super-Mare | 04:00 |

| 618 | Wigan | 04:00 |

| 620 | Wiltshire South West | 04:00 |

| 626 | Witham | 04:00 |

| 628 | Woking | 04:00 |

| 635 | Worcestershire West | 04:00 |

| 644 | Wyre Forest | 04:00 |

| 18 | Arundel & South Downs | 04:30 |

| 26 | Banbury | 04:30 |

| 37 | Batley & Spen | 04:30 |

| 51 | Berwickshire, Roxburgh & Selkirk | 04:30 |

| 54 | Bexhill & Battle | 04:30 |

| 58 | Birmingham Erdington | 04:30 |

| 96 | Brigg & Goole | 04:30 |

| 138 | Cheadle | 04:30 |

| 147 | Chippenham | 04:30 |

| 148 | Chipping Barnet | 04:30 |

| 152 | Clacton | 04:30 |

| 157 | Colchester | 04:30 |

| 158 | Colne Valley | 04:30 |

| 159 | Congleton | 04:30 |

| 161 | Corby | 04:30 |

| 169 | Crewe & Nantwich | 04:30 |

| 178 | Daventry | 04:30 |

| 187 | Devizes | 04:30 |

| 193 | Dewsbury | 04:30 |

| 235 | Elmet & Rothwell | 04:30 |

| 271 | Gordon | 04:30 |

| 275 | Gravesham | 04:30 |

| 297 | Harwich & Essex North | 04:30 |

| 301 | Hazel Grove | 04:30 |

| 309 | Hertfordshire North East | 04:30 |

| 319 | Horsham | 04:30 |

| 322 | Huddersfield | 04:30 |

| 328 | Ilford North | 04:30 |

| 329 | Ilford South | 04:30 |

| 340 | Kensington | 04:30 |

| 349 | Lancashire West | 04:30 |

| 351 | Leeds Central | 04:30 |

| 352 | Leeds East | 04:30 |

| 353 | Leeds North East | 04:30 |

| 354 | Leeds North West | 04:30 |

| 355 | Leeds West | 04:30 |

| 360 | Leicestershire South | 04:30 |

| 394 | Middlesbrough | 04:30 |

| 400 | Mole Valley | 04:30 |

| 405 | Morley & Outwood | 04:30 |

| 420 | Newton Abbot | 04:30 |

| 424 | Norfolk South | 04:30 |

| 430 | Norwich North | 04:30 |

| 431 | Norwich South | 04:30 |

| 461 | Pudsey | 04:30 |

| 466 | Redcar | 04:30 |

| 496 | Salisbury | 04:30 |

| 498 | Scunthorpe | 04:30 |

| 503 | Sheffield Brightside & Hillsborough | 04:30 |

| 504 | Sheffield Central | 04:30 |

| 505 | Sheffield Hallam | 04:30 |

| 506 | Sheffield Heeley | 04:30 |

| 507 | Sheffield South East | 04:30 |

| 510 | Shrewsbury & Atcham | 04:30 |

| 519 | Somerton & Frome | 04:30 |

| 532 | Stevenage | 04:30 |

| 534 | Stockport | 04:30 |

| 577 | Totnes | 04:30 |

| 582 | Tynemouth | 04:30 |

| 583 | Tyneside North | 04:30 |

| 619 | Wiltshire North | 04:30 |

| 627 | Witney | 04:30 |

| 630 | Wolverhampton North East | 04:30 |

| 631 | Wolverhampton South East | 04:30 |

| 632 | Wolverhampton South West | 04:30 |

| 9 | Altrincham & Sale West | 05:00 |

| 20 | Ashford | 05:00 |

| 36 | Bath | 05:00 |

| 39 | Beaconsfield | 05:00 |

| 52 | Bethnal Green & Bow | 05:00 |

| 53 | Beverley & Holderness | 05:00 |

| 56 | Birkenhead | 05:00 |

| 62 | Birmingham Northfield | 05:00 |

| 65 | Birmingham Yardley | 05:00 |

| 79 | Bootle | 05:00 |

| 80 | Boston & Skegness | 05:00 |

| 85 | Bradford East | 05:00 |

| 86 | Bradford South | 05:00 |

| 87 | Bradford West | 05:00 |

| 92 | Brentford & Isleworth | 05:00 |

| 97 | Brighton Kemptown | 05:00 |

| 98 | Brighton Pavilion | 05:00 |

| 110 | Burton | 05:00 |

| 115 | Caithness, Sutherland & Easter Ross | 05:00 |

| 116 | Calder Valley | 05:00 |

| 119 | Cambridge | 05:00 |

| 137 | Chatham & Aylesford | 05:00 |

| 146 | Chingford & Woodford Green | 05:00 |

| 149 | Chorley | 05:00 |

| 165 | Coventry North East | 05:00 |

| 166 | Coventry North West | 05:00 |

| 167 | Coventry South | 05:00 |

| 174 | Cynon Valley | 05:00 |

| 197 | Dorset Mid & Poole North | 05:00 |

| 198 | Dorset North | 05:00 |

| 199 | Dorset South | 05:00 |

| 218 | Ealing Central & Acton | 05:00 |

| 219 | Ealing North | 05:00 |

| 247 | Faversham & Kent Mid | 05:00 |

| 248 | Feltham & Heston | 05:00 |

| 249 | Fermanagh & South Tyrone | 05:00 |

| 252 | Finchley & Golders Green | 05:00 |

| 257 | Gainsborough | 05:00 |

| 274 | Grantham & Stamford | 05:00 |

| 282 | Halesowen & Rowley Regis | 05:00 |

| 284 | Haltemprice & Howden | 05:00 |

| 303 | Hemsworth | 05:00 |

| 304 | Hendon | 05:00 |

| 307 | Herefordshire North | 05:00 |

| 315 | Hitchin & Harpenden | 05:00 |

| 321 | Hove | 05:00 |

| 327 | Hyndburn | 05:00 |

| 331 | Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch & Strathspey | 05:00 |

| 338 | Keighley | 05:00 |

| 366 | Leyton & Wanstead | 05:00 |

| 370 | Liverpool Riverside | 05:00 |

| 371 | Liverpool Walton | 05:00 |

| 372 | Liverpool Wavertree | 05:00 |

| 373 | Liverpool West Derby | 05:00 |

| 378 | Louth & Horncastle | 05:00 |

| 384 | Maidstone & The Weald | 05:00 |

| 391 | Meon Valley | 05:00 |

| 410 | New Forest West | 05:00 |

| 426 | Normanton, Pontefract & Castleford | 05:00 |

| 454 | Pontypridd | 05:00 |

| 455 | Poole | 05:00 |

| 456 | Poplar & Limehouse | 05:00 |

| 470 | Rhondda | 05:00 |

| 472 | Richmond (Yorks) | 05:00 |

| 475 | Rochester & Strood | 05:00 |

| 480 | Rossendale & Darwen | 05:00 |

| 483 | Rugby | 05:00 |

| 488 | Rutland & Melton | 05:00 |

| 490 | St Albans | 05:00 |

| 495 | Salford & Eccles | 05:00 |

| 499 | Sedgefield | 05:00 |

| 500 | Sefton Central | 05:00 |

| 508 | Sherwood | 05:00 |

| 509 | Shipley | 05:00 |

| 512 | Sittingbourne & Sheppey | 05:00 |

| 518 | Somerset North East | 05:00 |

| 526 | Southport | 05:00 |

| 541 | Stourbridge | 05:00 |

| 543 | Stratford-on-Avon | 05:00 |

| 545 | Stretford & Urmston | 05:00 |

| 564 | Taunton Deane | 05:00 |

| 572 | Tiverton & Honiton | 05:00 |

| 575 | Torbay | 05:00 |

| 591 | Wakefield | 05:00 |

| 592 | Wallasey | 05:00 |

| 595 | Walthamstow | 05:00 |

| 599 | Warrington North | 05:00 |

| 600 | Warrington South | 05:00 |

| 622 | Winchester | 05:00 |

| 624 | Wirral South | 05:00 |

| 625 | Wirral West | 05:00 |

| 633 | Worcester | 05:00 |

| 637 | Worsley & Eccles South | 05:00 |

| 648 | York Central | 05:00 |

| 649 | York Outer | 05:00 |

| 650 | Yorkshire East | 05:00 |

| 22 | Aylesbury | 05:30 |

| 34 | Basingstoke | 05:30 |

| 57 | Birmingham Edgbaston | 05:30 |

| 60 | Birmingham Hodge Hill | 05:30 |

| 103 | Broadland | 05:30 |

| 108 | Buckingham | 05:30 |

| 123 | Cambridgeshire South East | 05:30 |

| 188 | Devon Central | 05:30 |

| 277 | Great Yarmouth | 05:30 |

| 283 | Halifax | 05:30 |

| 520 | South Holland & The Deepings | 05:30 |

| 605 | Waveney | 05:30 |

| 3 | Aberdeen North | 06:00 |

| 4 | Aberdeen South | 06:00 |

| 63 | Birmingham Perry Barr | 06:00 |

| 64 | Birmingham Selly Oak | 06:00 |

| 74 | Bognor Regis & Littlehampton | 06:00 |

| 126 | Cardiff Central | 06:00 |

| 127 | Cardiff North | 06:00 |

| 128 | Cardiff South & Penarth | 06:00 |

| 129 | Cardiff West | 06:00 |

| 220 | Ealing Southall | 06:00 |

| 254 | Forest of Dean | 06:00 |

| 261 | Gillingham & Rainham | 06:00 |

| 288 | Hampshire North East | 06:00 |

| 300 | Hayes & Harlington | 06:00 |

| 305 | Henley | 06:00 |

| 350 | Lancaster & Fleetwood | 06:00 |

| 404 | Morecambe & Lunesdale | 06:00 |

| 423 | Norfolk North West | 06:00 |

| 425 | Norfolk South West | 06:00 |

| 444 | Oxford West & Abingdon | 06:00 |

| 464 | Reading East | 06:00 |

| 465 | Reading West | 06:00 |

| 477 | Romford | 06:00 |

| 484 | Ruislip, Northwood & Pinner | 06:00 |

| 492 | St Helens North | 06:00 |

| 493 | St Helens South & Whiston | 06:00 |

| 511 | Shropshire North | 06:00 |

| 537 | Stoke-on-Trent Central | 06:00 |

| 538 | Stoke-on-Trent North | 06:00 |

| 539 | Stoke-on-Trent South | 06:00 |

| 563 | Tatton | 06:00 |

| 566 | Tewkesbury | 06:00 |

| 567 | Thanet North | 06:00 |

| 568 | Thanet South | 06:00 |

| 573 | Tonbridge & Malling | 06:00 |

| 587 | Uxbridge & Ruislip South | 06:00 |

| 597 | Wantage | 06:00 |

| 604 | Watford | 06:00 |

| 629 | Wokingham | 06:00 |

| 638 | Worthing East & Shoreham | 06:00 |

| 639 | Worthing West | 06:00 |

| 21 | Ashton Under Lyne | 06:30 |

| 59 | Birmingham Hall Green | 06:30 |

| 118 | Camborne & Redruth | 06:30 |

| 162 | Cornwall North | 06:30 |

| 163 | Cornwall South East | 06:30 |

| 180 | Denton & Reddish | 06:30 |

| 457 | Portsmouth North | 06:30 |

| 458 | Portsmouth South | 06:30 |

| 491 | St Austell & Newquay | 06:30 |

| 531 | Stalybridge & Hyde | 06:30 |

| 579 | Truro & Falmouth | 06:30 |

| 68 | Blackley & Broughton | 07:00 |

| 317 | Hornchurch & Upminster | 07:00 |

| 356 | Leicester East | 07:00 |

| 357 | Leicester South | 07:00 |

| 358 | Leicester West | 07:00 |

| 382 | Macclesfield | 07:00 |

| 387 | Manchester Central | 07:00 |

| 388 | Manchester Gorton | 07:00 |

| 389 | Manchester Withington | 07:00 |

| 397 | Milton Keynes North | 07:00 |

| 398 | Milton Keynes South | 07:00 |

| 439 | Oldham East & Saddleworth | 07:00 |

| 440 | Oldham West & Royton | 07:00 |

| 479 | Ross, Skye & Lochaber | 07:00 |

| 609 | Wells | 07:00 |

| 645 | Wythenshawe & Sale East | 07:00 |

| 50 | Berwick-upon-Tweed | 12:00 |

| 73 | Blyth Valley | 12:00 |

| 312 | Hexham | 12:00 |

| 339 | Kenilworth & Southam | 12:00 |

| 596 | Wansbeck | 12:00 |

| 601 | Warwick & Leamington | 12:00 |

| 494 | St Ives | 13:00 |

May 03 2015

Clown-car democracy

As the general election approaches we are being urged to vote, often with the pious imprecation that it doesn’t matter who we vote for just so long as we vote, because voting is important. After the election we will be told that we have spoken, meaning will be drawn from the deconstructed lemon cheesecake of the results.

But it’s all a bit of a lie: we live in a clown-car democracy.

Come May the 7th we’ll all leap into the clown-car and try to make it bend to our wishes. Some will try to honk the horn and get water squirted in the face for our troubles, others will wrench the steering wheel to the left or right and discover themselves heading in completely different directions. A bouquet of flowers will spring from the exhaust when someone puts an indicator on. The ringmaster will look cheery throughout.

We’ve all been trained to think that it’s entirely reasonable that a party might get 10% of the votes in the country but only one MP out of 650; that a party with a little over a third of the vote should have absolute power; that our political opponents can be described as “scum”. We’ve all been trained to accept sordid sexual metaphors when grown ups work together despite differences.

May 02 2015

Book review: The Information Capital by James Cheshire and Oliver Uberti

Today I review  The Information Capital by James Cheshire and Oliver Uberti – a birthday present. This is something of a coffee table book containing a range of visualisations pertaining to data about London. The book has a website where you can see what I’m talking about (here) and many of the visualisations can be found on James Cheshire’s mappinglondon.co.uk website.

The Information Capital by James Cheshire and Oliver Uberti – a birthday present. This is something of a coffee table book containing a range of visualisations pertaining to data about London. The book has a website where you can see what I’m talking about (here) and many of the visualisations can be found on James Cheshire’s mappinglondon.co.uk website.

This type of book is very much after my own heart, see for example my visualisation of the London Underground. The Information Capital isn’t just pretty, the text is sufficient to tell you what’s going on and find out more.

The book is divided into five broad themes “Where We Are”, “Who We Are”, “Where We Go”, “How We’re Doing” and “What We Like”. Inevitably the majority of the visualisations are variants on a coloured map but that’s no issue to my mind (I like maps!).

Aesthetically I liked the pointillist plots of the trees in Southwark, each tree gets a dot, coloured by species and the collection of points marks out the roads and green spaces of the borough. The twitter map of the city with the dots coloured by the country of origin of the tweeter is in similar style with a great horde evident around the heart of London in Soho.

The visualisations of commuting look like thistledown, white on a dark blue background, and as a bonus you can see all of southern England, not just London. You can see it on the website (here). A Voroni tessellation showing the capital divided up by the area of influence (or at least the distance to) different brands of supermarket is very striking. To the non-scientist this visualisation probably has a Cubist feel to it.

Some of the charts are a bit bewildering, for instance a tree diagram linking wards by the prevalent profession is confusing and the colouring doesn’t help. The mood of Londoners is shown using Chernoff faces, this is based on data from the ONS who have been asking questions on life satisfaction, purpose, happiness and anxiety since 2011. On first glance this chart is difficult to read but the legend clarifies for us to discover that people are stressed, anxious and unhappy in Islington but perky in Bromley. You can see this visualisation on the web site of the book (here).

The London Guilds as app icons is rather nice, there’s not a huge amount of data in the chart but I was intrigued to learn that guilds are still being created, the most recent being the Art Scholars created in February 2014. Similarly the protected views of London chart is simply a collection of water-colour vistas.

I have mixed feelings about London, it is packed with interesting things and has a long and rich history. There are even islands of tranquillity, I enjoyed glorious breakfasts on the terrace of Somerset House last summer and lunches in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. But I’ve no desire to live there. London sucks everything in from the rest of the country, government sits there and siting civic projects outside London seems a great and special effort for them. There is an assumption that you will come to London to serve. The inhabitants seem to live miserable lives with overpriced property and hideous commutes, these things are reflected in some of the visualisations in this book. My second London Underground visualisation measured the walking time between Tube station stops, mainly to help me avoid that hellish place at rush hour. There is a version of such a map in The Information Capital.

For those living outside London, The Information Capital is something we can think about implementing in our own area. For some charts this is quite feasible based, as they are, on government data which covers the nation such as the census or GP prescribing data. Visualisations based on social media are likely also doable although will lack weight of numbers. The visualisations harking back to classics such as John Snow’s cholera map or Charles Booth’s poverty maps of are more difficult since there is no comparison to be made in other parts of the country. And other regions of the UK don’t have Boris Bikes (or Boris, for that matter) or the Millennium Wheel.

It’s completely unsurprising to see Tufte credited in the end papers of The Information Capital. There are also some good references there for the history of London, places to get data and data visualisation.

I loved this book, its full of interesting and creative visualisations, an inspiration!

Apr 28 2015

A letter to a constituent…

A constituent wrote to me asking why he received lots of election literature from Labour, Tory and UKIP candidates and not so much from the Liberal Democrats, this was my reply:

You should expect to get one Liberal Democrat leaflet over the campaign, for parliamentary elections each party gets one freepost per constituency, I received mine today. Other literature is funded by the local party, for example we’re paying for a wraparound advert on one of the local newspapers which you might see (that will cost £1000s). Aside from that I have about 300 leaflets sitting on the floor next to me waiting for delivery – it’ll take me about 3 hours to deliver them by hand. Parliamentary constituencies have about 50000 voters so it costs hundreds of pounds to print a leaflet for everyone and thousands of hours to deliver them. The City of Chester Liberal Democrats Party is quite small (a hundred or so members), and we don’t have a huge amount of money hence you receive very few leaflets.

If you see a poster in someone’s window it’s either because they are a party member or because the Liberal Democrats have canvassed (knocked on the door and asked who they will vote for) the occupant and they’ve agreed to put up a poster. Canvassing is more time consuming than leafleting, if you lived in the Hoole Ward of the city then you will likely have been canvassed and also seen Mark Williams, Alan Rollo and Bob Thompson doing their "street surgery" on the high street because Bob is local councillor for that ward (the only Liberal Democrat councillor on the local authority) and so it’s a target for the forthcoming local elections which are run on the same day as the parliamentary elections.

Nationally, the Liberal Democrats target resources to winnable seats, at the 2010 elections we targeted Wrexham and Warrington South as local seats we might win. This is because under the first past the post electoral system it doesn’t matter what your national share of the vote is, it doesn’t matter what your share of the vote is in any particular constituency. The important thing is to have more votes than any of your opponents in a constituency. Since the 2010 election we’ve lost a lot of local councillors, and all of the MPs we currently have are under threat. So we are targeting resources at the constituencies we currently hold (with a very few exceptions) and hoping to keep as many of those as possible. As an example I get regular emails from the national party asking for help in getting Lisa Smart elected in Hazel Grove.

The City of Chester is a Labour/Conservative marginal – hence the visits by David Cameron and Ed Miliband over the last couple of weeks, and the large number of leaflets from their parties.

Other Liberal Democrats might be a bit miserable about all this but I joined the party in 1989 and the first general election I was involved in (1992), we got 20 seats and we should do better than that this time.

Hope that answers your question, and that you vote for Bob Thompson!