Author's posts

Sep 15 2012

Harlech

Our first holiday with Thomas, now aged 7 months, it promised to be rather different from previous ones! We headed for North Wales since it is close and has a seaside.

Our first holiday with Thomas, now aged 7 months, it promised to be rather different from previous ones! We headed for North Wales since it is close and has a seaside.

We booked Rhiwgoch Bach, a cottage above Harlech, proprietors Ieuan and Gwen Edwards. Gwen provides rather fine Welsh cakes (somewhere between a scone and a biscuit) as a welcome gift. Thomas fell asleep just before we left Chester at 9am and awoke as we arrived a little after 11am. The drive from Chester is straightforward and rather scenic although the final stretch is up from Harlech is a narrow, steep twisting lane hemmed in at both sides by high stone walls with limited passing places. This is the route provided in the instructions to get to the cottage, it makes for a simple description but there is an alternative, rather less exciting route.

The cottage has a large, well-equipped kitchen there is a little private garden – if only the weather had been fine enough to sit out in it. The views from the cottage are spectacular, out over the sea to the Llŷn peninsula, South to rocky Foel Ddu, surrounded by rough farmland.

Day 1 – Saturday

In the afternoon we visited Harlech, it clings to the side of a steep drop down to the sea with the castle sitting on a rocky promontory.

The weather was warm, mainly sunny. Sunset over the Llŷn peninsula was glorious.

Thomas helped us with some stargazing by waking us a couple of hours after he’d gone to bed. In a perfectly clear sky, with little light pollution (apart from the cottage security lights), we saw the Milky Way.

Day 2 – Sunday

The weather more overcast today, in the morning we went down to Harlech beach, a huge expanse of sand. In the afternoon we walked up the road and headed to Foel Senigl, a little hill. We didn’t quite reach the top because the track from the road didn’t lead there. As the afternoon drew on the clouds came in and it rained, and was windy.

Thomas was happy in the cot until about midnight.

Day 3 – Monday

Rain menaced for most of the day, in the morning we went to Porthmadog to do some food shopping. The harbour is pleasant enough and there are a number historic railways.

The rest of the town I found a bit grim.

In the afternoon we went to the beach at Llandanwg, this is closest to the cottage and on a rather more manageable scale than Harlech beach. It has rockpools but more comprised rocks on sand than rocks with holes in them. Behind the beach is a small church with a graveyard full of old slate gravestones, and some short-cropped grass leading down to an estuary.

Thomas has his first tooth, it’s one of his lower incisors – it isn’t visible but to the touch his gum feels toothy rather than gummy.

Day 4 – Tuesday

A little surprised to find the weather relatively clear, but very breezy. We headed down the road to Barmouth which is a Victorian seaside resort. It has a lengthy promenade to walk along and once again the harbour area is pleasant with some fine stone buildings, the town has some fine old stone buildings and a lot of shops selling seaside tat.

It seems to have a lot of tattoo parlours for its size, and a disturbingly named “arousal Café”, surely the result of a lost letter.

In the afternoon the weather continued fine so we went to Harlech castle, this turns out to be a high value for money investment – the castle has a spectacular location looking out from a rocky promontory across the estuary to Porthmadog and the hills of the Llŷn peninsula. The castle itself is relatively intact, the outer walls almost complete but with most of the internal structure gone. It is possible to walk around the parapets. There is a small park along the road out of Harlech, going south, from which you get a good exterior view of the castle.

The sky was clear in the early evening so I had a go at some photography of the night sky, this worked surprisingly well, I have pictures of the Milky Way. I was held back a bit by not knowing how to use my planisphere, the unturn-offable security light and by the fact that constellation naming is more than a little random.

Day 5 – Wednesday

In the morning we went to see the Nantcol waterfall up the valley from Llanbedr. This involved a bit of rough walking, although nothing compared to previous holidays!

In the afternoon the weather took a turn for the worse, the wind howled impressively around the cottage, we disappeared into a wet cloud and slept.

Day 6 – Thursday

Our last day in Harlech, in the morning we visited Portmeirion which was in the midst of preparations for the No. 6 festival. The village is bizarre but attractive it’s the sort of weird mock-Italianate style I might adopt if I had money to burn.

As well as the village the coast on the estate is very fine with views out across the estuary.

In the afternoon we went down again to a blustery Llandanwg beach.

We returned home on Friday morning, Thomas sleeping all the way home.

More photos here.

Sep 01 2012

GCSE results through the ages

This year there is a fuss because GCSE pass results have not gone up as anticipated. Ultimately this turns out to be an issue with a new English exam which was marked generously in the January sitting when compared to the June sitting, thus relatively disadvantaging the later sitting in this year.

But aside from this, here is an graph showing pass rates for GCSEs since they started in the late eighties:

(source: BBC News)

A steady increase in those achieving grades A-C from 40% when the exam was introduced in 1988 to over 60% now. Never mind the unfairness within this year, what about those disadvantaged by taking the exams a few short years ago?

This behaviour is also reflected in A-level results, below is a graph showing the percentage of A grades since the 1970s.

(source: BBC News)

We examine students for several reasons:

1. To provide confirmation that they know certain things in order to be accepted onto further courses or employment;

2. To provide “ranking” information so we might pick the “best” candidates either to accept onto a course, or to employ;

3. To measure the performance of schools, arguably this is a serious misuse of examinations.

It would appear our examination system is focused on 2 rather than 1 but is not sensitive because ever more people are awarded higher grades each year which means distinguishing the best students is ever harder, and the graphs above suggest we cannot make year to year comparisons.

Previously A grades at A-level were awarded as a fixed proportion of the cohort, similarly the other grades. So for example the students with the top 8% marks were awarded an A grade. This scheme has some merit: it assumes that that students have the same performance distribution year on year and uses this property to derive grade boundaries.

My performance at work is graded in a similar way; in my case this is a poor scheme – there are no objective measures of my performance against my colleagues in the form of an exam. Furthermore the distribution is enforced in groups of less than 20 people; there are statistical tests to establish whether a distribution of grades matches a prescribed distribution – these tests come with a caveat that they are invalid for samples smaller than about 50.

However, for a schools examination system these problems are rather less relevant: we have an objective examination system and a cohort of thousands. The current system asks us to believe that every year students are getting better and better: todays A-level students are three times as good as the A-level students of the 1980s, and the GCSE students of today are 50% better than those of the 1980s. Most people outside the education system will find this difficult to believe, and not just because they took their exams in the “olden days”. For the record: I took my A-levels in 1988, and the old fashioned O’ levels in 1986 prior to the introduction of the GCSE.

The current scheme has a strong whiff of political necessity: how can you show your changes to the education system are a success if your marking system is such that grades are awarded in fixed proportion? The current system allows you to show year on year advances, like the production of tractors in the Soviet Union.

Aug 22 2012

Expertise in the House of Lords

House of Lords reform is now in the news, with the recent introduction of a Bill followed by a vote in favour of a second reading but the withdrawal of the timetable motion which would smooth the passage of the bill through parliament*. In this post I’d like to address a recent report published by the Campaign for Science and Engineering (CaSE) on the impact of the proposed reforms on expertise in the House of Lords. CaSE is an advocacy organisation which is run with the support of a wide range of universities, learned societies, charities and technology companies.

The CaSE report on the House of Lords is well worth a read, it has a nice summary of what is meant by expertise, the proposed reforms, international comparisons, opinion from a survey of a small group of Lords and some specific examples of the influence of the Lords in the area of science and technology: specifically the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill (2008), Health and Social Care Bill 2011 (adding research as a core goal), and the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee Report on Nuclear Research and Development capabilities (2011).

The report ends with some proposals which, are as follows:

- a 30% appointed House of Lords, rather than 20%;

- a fully independent Appointments Commission;

- more employees with STEM degrees in the civil service supporting the House of Lords;

- increased not decreased resources for the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee;

- compulsory training in STEM for MPs and Lords.

As an aside, it is possible that professional politicians are indifferent to the statement in the report that the Lords have provided the present government with fifty defeats in 2 years, in support of the idea that they are an important revising chamber, but to me it seems like a poor way to win friends and influence people in government.

Returning to the measures proposed: two of these measures I support, one requires some clarification and two I don’t support. I support a fully independent Appointments Commission, this is the logic of a largely elected upper house with an Appointments Commission whose role is to populate the non-elected element. I believe the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee requires at least flat resources.

I provide my objections to increasing the proposed level of appointments from 20% to 30% in following bullet form:

- The House of Lords is a largely political house which carries out a political function: it provides a check on legislation originally drafted in the House of Commons. In my view this means that it should be elected to give democratic legitimacy to the role it plays. The current proposal for Lords reform contain an allowance for 20% of the upper chamber to be appointed, including Bishops from the Church of England, I see this as a necessary concession in order to gain wider acceptance which goes against democratic principles. The figure of 20% broadly matches the number of crossbench Peers in the current house, expanding this concession is undesirable;

- my second objection is against special pleading: this proposal is asking for special treatment for a particular group in society (scientists and engineers), if it applies to them why not to other groups? Should other religious groups have guaranteed representation? What about the lucrative football industry?

- the contents of the report do not provide supporting evidence for the level of appointments they propose; indeed James Wilsdon’s section on expertise highlights how expertise is available to the Lords via the civil service and the committee system and quotes Lord Rees in saying that “we are all depressingly ‘lay’ outside our expertise”;

- Once you’ve gone to the trouble of appointing scientists to the House of Lords are they actually going to turn up to vote? Lord Rees, Lord Krebs and Baroness Finlay are explicitly mentioned by the report, they have attendances to vote of, respectively 12% since 2005, 9% since 2007 and 39% since 2001.

If we, as scientists and engineers, want more representation in the reformed, elected House of Lords we should be standing for election, not pleading for special treatment.

The proposal for more scientists and engineers in the civil service requires some more investigation: are scientists and engineers applying to the civil service? If not I can imagine why: long ago as a shiny, new graduate I considered applying to the civil service but my strong impression was that the types of jobs available would not match my skills. Except in specialist areas there are no labs in the civil service, and the alternative on offer seemed to involve rather more essay-style writing for which I, trained as a scientist, was woefully under-prepared.

Compulsory courses in STEM for new Lords and MPs are superficially attractive, a voluntary course was offered following the 2010 General Election, with an uptake of 12; given this low take up it seems to me that such a course is not falling on fertile ground, I know my approach to such compulsion in work-related courses: rather surly looks and a considerable antipathy to what the company has forced me to learn.

The Tories have long opposed bringing an elected element to the House of Lords despite the Coalition Agreement we can expect them to provide luke-warm support for the proposed reforms. Labour have long had the reform of the House of Lords as a policy, they made significant changes in 1999 principally to remove the hereditary (frequently Tory) Peers but, once they had addressed the disadvantage they felt, they appear to have lost interest in further reform. We can expect Labour to make every appearance of supporting reform of the Lords whilst doing everything in their power procedurally in the Commons to block the proposed changes and indeed use those procedures to disrupt other government legislation. Except for a few recidivist Liberal Democrat peers we should expect to see uniform support for the House of Lords reform from Liberal Democrats in parliament.

The way this Bill will die is by none of the supporters of Lords Reform accepting anything but their own Lords Reform proposal.

References

CaSE House of Lords and Expertise report, June 2012

*Since I wrote this the reforms have been dropped: (link)

Aug 18 2012

Sharepoint–how do I hate thee?

Sharepoint is Microsoft’s document sharing and collaboration tool. It allows you to share and manage documents, and to build websites – so it’s a content management system too. For work I am strapped to the mast of Sharepoint: we need to share files across the world, previously we used shared network drives, as a byproduct individual teams can also create websites. There are close on 100,000 of us.

The file sharing/content management schizophrenia can lead to horrible websites, on a normal website you might expect that following a link in a page will take you seamlessly to another web page to be rendered in your browser. Not in Sharepoint: the siren voice of the file sharing side means that all to often website authors are going to link you to documents – so you hit a link and if you’re lucky you get asked whether you want to open a document in Microsoft Office, if you’re unlucky you get asked to enter your credentials first. Either way it breaks your expectation as to what a website should do: hit link – go to another webpage.

For every function you can imagine Sharepoint has a tick in the box:

- Blogging – tick.

- Social media – tick.

- Wiki – tick.

- Discussion forums – tick.

- Version control – tick.

The problem is that whilst it nominally ticks these boxes it is uniformly awful at implementing them. I’ve used WordPress and Blogger for blogging, phpBB for discussion forums, moinmoin and Project Forum wiki software, source control software, twitter, delicious, bit.ly, Yammer for social media and in comparison Sharepoint’s equivalent is laughable.

This ineptitude has spawned a whole industry of companies plugging the gaps.

Sharepoint does feature some neat integration into Microsoft Office: viewing shared calendars in Outlook, saving directly to Sharepoint from office application but this facility is a bit flakey – Office will try to auto-populate a "My SharePoint sites" area but does it via a cryptic set of rules which can’t be relied on to give you access to all of your sites.

For the technically minded part of the problem is the underlying product but part of the problem is down to how your company decides to implement Sharepoint. My WordPress-based site looks pretty much how I want it, bar the odd area where my CSS-fu has proved inadequate. In a corporate Sharepoint environment other people’s design decisions are foisted upon me, although Sharepoint’s underlying design often seems to be the root of the problem

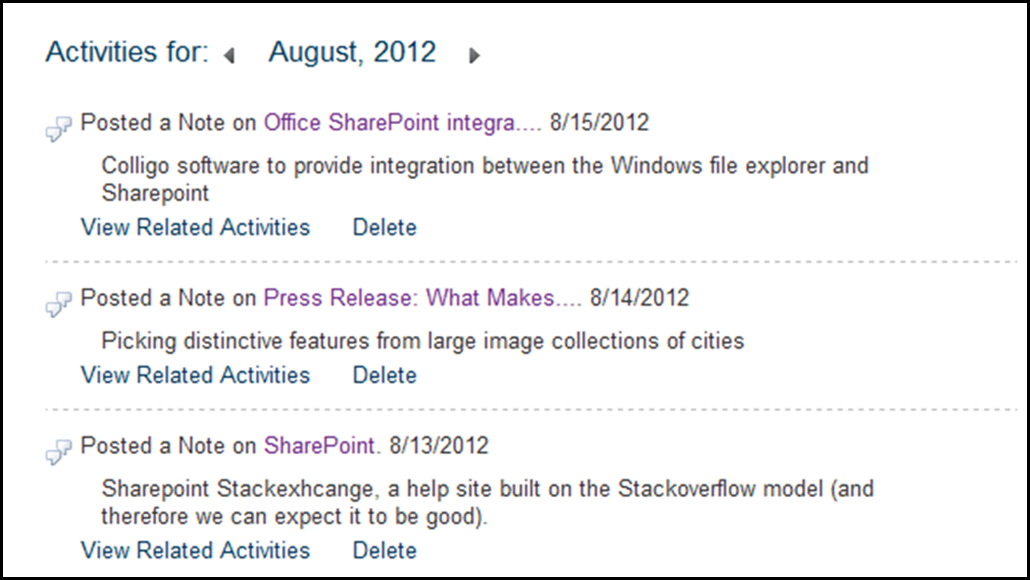

Take this piece of design (shown below), this is part of the new Sharepoint social media facilities but it’s ugly as sin, most of what you see for each Note is Sharepoint boilerplate (Posted a note on – View Related Activities – Delete) rather than your content, furthermore I have repeatedly set my dates to format dd/mm/yyyy in the UK style and this part of my site remains steadfastly on the US mm/dd/yyyy format.

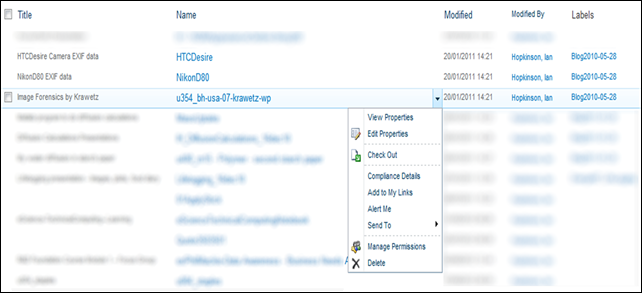

Here’s another nasty piece of design.The core of the document sharing facility is the Document Library, below is a default view of one of my libraries (with some blurring). All of the Sharepointy magic for a document is run off a dropdown menu accessed via a small downward pointing triangle on the "Name" field, the little triangle is only visible when you float over that particular line, note also that if you click on the name in the name field then that takes you to the document – so you trigger two different behaviours in one field.

Other items in this table are hyperlinks but take you to entirely uninteresting content.

It didn’t have to be this way, the Document Library could functionality could have been integrated into the Windows File Explorer. Applications like the source control software TortoiseSVN and TortoiseHG do this, putting little overlays onto file icons and providing functionality via the right click menu. Windows 7 even has a panel at the bottom of the screen which seems to offer quasi-Sharepoint functionality – you can set tags for documents which could map to the "properties" that Sharepoint uses.

Users are familiar with the file explorer, Sharepoint discards that familiarity for a new, clunky web-based alternative. Furthermore users sharing files are often moving from a directory-based shared hard-drive scheme, Sharepoint allows you to use directories in Document Libraries but it breaks the property-based view which is arguably a better scheme but forcing users over to it wholesale is unreasonable.

In summary: Sharepoint suffers from trying to be a system to share documents and a system for making websites. It features a poor web interface for functionality which could be integrated into the Windows file explorer.

Aug 14 2012

Why I’m a liberal, and Giles Fraser isn’t