Author's posts

Nov 09 2010

A diversion in my life

In the past my blog was my diary, which was entirely private. I kept a diary on my Psion for a number of years before the feeling that I should make a daily, or at least a regular, entry on the minutiae of my life became oppressive and I gave up. More recently I resumed as a blogger, and rather than writing down minutiae I wrote in a more formal, extended style on things that were happening, or on my mind, for a more public audience. It still provided a record of what I thought when.

This post is difficult in the sense that it is somewhat private: I had a minor operation on the 23rd September and only now am I about to go back to work. My minor operation turned out to be a little more complicated then expected. The aftermath has taken up a significant portion of my time and dominated my thoughts for the last 6 weeks. I hasten to add that at no time has my life (or any part of my body) been at serious risk and I have only occasionally been in minor, localised pain and been a little inconvenienced. This is all a storm in a tiny little teacup, but it is my teacup and I have had some sort interesting experience along the way.

I will be circumspect about the exact nature of my affliction. I started with a visit to a GP, who packed me off to the consultant at my local hospital. This is where I had my “unexpected prostate examination”. *That* wasn’t the affected part! A useful experience really, because at some point later in my life a semi-regular prostate exam will probably be a good idea and to be honest, there’s nothing to it. Warning signs: men, if you are semi-clad and a doctor asks you to roll on your side and pull your knees up to your chest – ask him why first!

I have medical insurance as a taxable benefit of my job. My initial intention was to stick with the NHS – my local hospital is over the road from where I live, whilst the private hospital, I believed, was many miles away. It turned out the private hospital was closer, and the wait was shorter and the consultant clearly thought me mad for not exercising my insurance. My initial private consultation was just 4 days after I raised the issue, on a Saturday morning, with potentially my operation the following Thursday. As it was the operation was delayed a few weeks because I had visitors at work on the Friday coming from Sweden – and it seemed wrong to bounce them and then my surgeon was going on holiday, to Sweden, for a couple of weeks. Compare this with initial consultation wait of 1 month, and operation scheduled for almost three months later on the NHS. I don’t see this as a criticism of the NHS: to provide fast service requires that you have more capacity than you strictly need – we choose not to fund the NHS to that level. I’ve been very happy with my local NHS GP service, and the quality of the medical care they provide – I’m sure that the quality of the medical care I would have received from the local hospital would be similarly excellent.

The nice things about private medicine are: it happens pretty quickly (and conveniently), the surroundings are nice and you’re better separated from your fellow man. The people who join you in private medical care may or may not be more pleasant than those with whom you are treated with in the NHS but they do not generally share a room with you!

I didn’t sleep the night before my operation: I’d never had a general anaesthetic before and to be honest I was a little bit scared – it didn’t help that I’m passingly familiar with historical pre-anaesthesia tales of operations for bladder stones and a mastectomy: I had a minor fear that I would be fully conscious but unable to communicate. I was also scared I wouldn’t have my operation, because to be honest things were getting a bit difficult. My final fear was that I would wake from my anaesthetic with caffeine withdrawal – I’d been fasting for the previous 18 hours or so.

To start the day of my operation properly a wasp stung me on my toe!

General anaesthesia is extinction: there is consciousness, there is nothing, there is consciousness. Chatting to the anaesthetist as I went under I discovered I was getting propofol. I suspect the porters tasked with returning post-operative patients to their rooms have a collection of the most utter gibberish known to man. For my part I supplied them with the prime factors of my room number: 2 and 13, thank you for asking.

The first week or so after my operation passed easily, I’d expected to be off work for a week and I had some books to read. I even made a new website for the Chester Liberal Democrats. The next week or so it sort of dawned on me that the consultants slightly sweaty brow after the operation and the advice that I would take “a long time to heal” did mean something and I was indeed going to take “a long time to heal”. So here I am 6 weeks later during which I’ve largely been confined to the house.

Somewhat surprisingly I’ve done OK: I’ve read a lot, I’ve fiddled around with various computer programs, blogged a bit, shredded many old bills, re-organised things and not watched daytime TV and not even listened to the radio a great deal.

A visit to the consultant at about week 3 was somewhat surprising – I didn’t things were going too well, he thought they were going great! He has always appeared somewhat disdainful of patients, GP’s and a willingness to prescribe antibiotics for imaginary infection. He said mine was one of the more difficult operations of my type that he’d done. I suspect he wanted the medal I claimed for myself on that one.

The doctor (and consultants) views on the solubility of soluble stitches are quaint – their reported view is that they dissolve in 10-14 days. I started off with 20 stitches, six weeks ago. Number of stitches which have disappeared through dissolution: 3; Number that I’ve helped out: 12. Number remaining: 5. The nurse seemed a bit more clued up and said they “took ages”. I suspect the problem is that patients assume that they shouldn’t tell the doctor they’ve been fiddling with their stitches, so the doctor continues in the happy belief that stitches dissolve.

So that’s the story of my last 6 weeks, the funniest thing in all this is something my dad said; unfortunately it makes it pretty much absolutely clear what my operation was, and so I might leave it to an ephemeral tweet.

Nov 09 2010

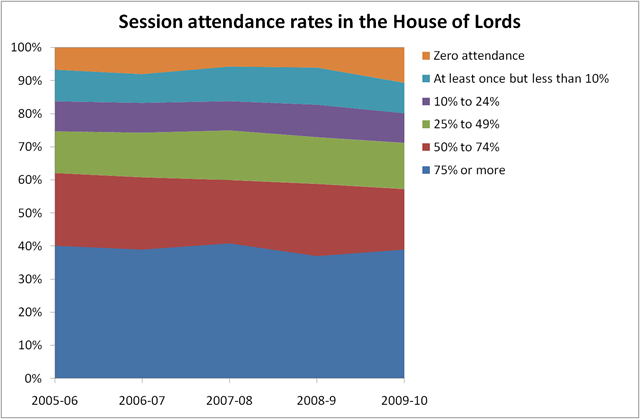

Poor attendance record in the House of Lords?

I know my readers love a chart, and today I found some data I thought was begging for a good graphing. It’s the attendance figures for the House of Lords found in a report entitled “Members Leaving the House” – found at the bottom of this article. The motivation for the report is to explore the idea of retirement for peers, something some peers are seeking regardless of any other changes taking place. A secondary motivation is that there is wider reform of the House of Lords proposed, and one of the issues is that the new House is envisaged, ultimately to have substantially fewer members – this type of discussion informs how that transition might be achieved.

The report contains a set of tables for the last five years indicating the fraction of sessions which peers attended broken down into groups:

- Attended 75% or more sessions

- 50% to 74%

- 25% to 49%

- 10% to 24%

- Attended at least once but less than 10%

- Zero attendance

This is what the data looks like:

To give some idea of scale: across the period shown here the total number of peers decreased from 777 to 741, the average number of sessions in a year was 140, this latter figure means that a peer attending “less than 10% of sessions” was attending less than twice. It compares with the number of working days in the year of approximately 240 (48*5 day weeks). Nearly 20% of peers attend a session in the House of Lords only once or twice a year.

Being a member of the House of Lords isn’t a proper job, it does not attract a salary, although peers may claim a subsistence and office allowance of up to £26,000 per year. In this sense we should not anticipate the levels of attendance achieved by those working “normally”. Some of the peers will be paid as government or opposition working peers. However, peers do have a direct effect on the laws the country makes and turning up twice a year (which is all 20% of them achieve) does suggest a fairly low degree of interest – if I did something twice a year I wouldn’t even consider it a hobby, I go to the dentist more often!

Nov 05 2010

A Coalition candidate for Oldham East and Saddleworth?

Following the news that Phil Woolas has lost his seat of Oldham East and Saddleworth for knowingly lying about his opponent, Graeme Archer has proposed on Conservative Home that the Coalition should put up a joint candidate selected in an open primary. Much as I respect Graeme on this I disagree, although I should point out this is a cautious rather than an emphatic rejection.

The function of a by-election is to selection an MP to represent a constituency in parliament, at a General Election this selection – repeated across the country – amounts to a decision on who should form the government. The General Election this year demonstrated that decision may not be clear.

Speaking from the point of view of a Liberal Democrat, potentially giving up the race in this seat would be damaging – it plays directly to the idea that the Liberal Democrats have been subsumed into the Tories. Should the LibDem candidate win in the Open Primary they would, almost inevitably be seen as the Coalition rather than the LibDem candidate. The great risk that the LibDems face during the Coalition is that as a minority party in a coalition they will be electorally damaged at the next General Election – this is observed in coalitions across Europe.

Successfully contesting a three-way election would illustrate how by-elections under coalition work, something that has been demonstrated already in the Thirsk and Malton by-election held over the summer. Furthermore it would help maintain the separate identity of the Liberal Democrats. I can join the Tory Party whenever I want, but I don’t want to – it is so blinding obvious to party members that the merger of the two parties is undesirable that amongst party members it is not even worth talking about. The public, and commentators need convincing of this.

From the point of view of the Coalition the situation is less clear cut, offering a combined candidate does demonstrate the joint nature of the Coalition, and the opportunity to argue the Coalition’s joint platform. However, at this point in a Government it would be difficult to see the by-election as a true referendum on their joint record, there are better ways of doing this than a by-election in a single constituency under special circumstances.

From a more practical point of view, as Tory Radio points out, it is more than likely that a faction within the losing party of the Open Primary would put up their own candidate.

Rather playfully I will point out to Graeme that the Open Primary followed by election scheme contains elements of an ad hoc election by alternative vote in the sense that there are multiple rounds of voting with candidates dropping out at different stages.

Nov 05 2010

Why the other ways don’t work

In my last blog post I calculated how to raise money for various things (getting rid of tuition fees, avoiding any benefit reductions and so forth) using income tax; originally the more ranty bit to be found in this post was included, but it was getting a bit long so I separated analysis and rant.

Since the election there’s been a great deal of discussion of cuts, largely this has been framed in terms of a cut to X being apocalyptic where X is some area supported by its interest group. There has been rather less focus on what should happen in place of such cuts, proposing an alternative area for increased cuts has generally been tried: “waste, foreigners in the form of international development, benefit scroungers, Trident“ are ever popular – each of these contributes about £1bn or so per annum in spending – the gap we’re trying to match is about £80bn per annum. There have been some proposals for increased taxes to be paid by “someone else”, an increase in VAT met with considerable opposition (VAT is the third biggest element of tax – the change would raise about £13bn per annum), as was an attempt to cut child benefit for higher rate tax payers, raising about £2.5billion per annum.

The favoured targets for increased taxes are “the rich” and “tax avoidance”. “The rich” are normally defined as “richer than me and the people I know”, which is a poor definition. Tax avoidance, according to an HMRC report under the last government the size of the tax gap – the sum of avoidance (legal) and tax evasion (illegal) was around £40bn per annum. This is disputed with Tax Research UK giving a figure three times larger at £120bn. It’s difficult to see exactly how they manage such a high estimate – it’s seems to be based around the size of the “shadow economy” – things like illegal working. Regardless of this actually collecting the money involved in the tax gap would appear to be difficult: as announced by Danny Alexander there’s a hope that spending £200million per year will result in a tax recovery of £7bn per year. There’s an implicit assumption in tax avoidance that again it’s “the rich” who are responsible but it seem clear from reading the HMRC document that successfully addressing the tax gap would probably impact quite broadly. For example, buying wine in Calais is a tax avoidance; as is paying the builder, decorator and so forth in cash; as is purchasing items in Hong Kong via ebay. The company I work for has changed the way it pays some of my pension contributions to reduce the tax paid – presumably this would count as a tax avoidance too.

Vodafone is in the news at the moment for a £6bn tax avoidance. The £6bn figure is as calculated by Private Eye and is described by HMRC as “an urban myth”; Vodafone appears to have made provision of £2.2bn to address this issue and ultimately paid £1.25bn. It’s worth pointing out that the £6bn figure, accrued over 10 years is typically compared by protestors with a *yearly* benefit cut of £7bn. This sort of presentation leads me to believe that the proposer is somewhere on the innumerate-dishonest scale and discount whatever else they are saying. Taking the Private Eye “high” estimate this is £600million per year, taking the difference between the amount actually paid and the “low” estimate it amounts to £100million per year. Vodafone appears to have paid around £1bn tax on profit in 2009 amounting to a rate of 25% in that year, so it is not true that they pay “no tax”. It’s also worth noting that Vodafone appear to have the legal upper hand in the situation, given a judgement in the European Court of Justice.

At one time Trident or its replacement were cited as a source of ready cash – again the presented cost of up to £100bn is for the entire lifetime of the system of up to fifty years or so i.e. between £1bn and £2bn a year, regardless of this the decision on Trident has been pushed into the future (i.e. beyond the next election). A more likely figure for the Trident replacement is £20bn, or at most £34bn. I’ve said previously that I consider Trident to be Cold War willy-waving but scrapping it is not a big impact – particularly if there is any sort of replacement.

A useful rule of thumb for all these situations seems to be:

- Check that tax gain and spending are being compared on the same time period.

- Divide quoted tax gain by at least three since that will get you back to a more generally accepted figure.

The latest wheeze is chasing George Osborne for a £1.6million tax bill. Referring to our list above, (1) is met admirably this bill would be payable once, on the death of his father. Experience suggests the figure of £1.6million is fanciful. David Mitchell puts this so much better than me here in the Observer. It’s not that I am in favour of tax avoidance I just see efforts to address the problem by individual harassment as pointless. What is needed, as Mitchell points out, are changes in the law so that tax avoidance becomes tax evasion and is then illegal. It’s ridiculous to expect people to pay tax that they don’t legally have to – it’s not what the great majority of the population do – why expect companies and the rich to do any different?

I’ve yet to see any figures on the “cut deficit through growth scheme”, a priori I’m dubious since the ability of government to influence growth seems marginal and any scheme would need to stretch out beyond the 10 years that even Labour were planning to cut the deficit in by which time using my state-of-the-art recession prediction algorithm we will have experienced another recession, and another addition to the deficit.

I’m uncomfortable with the idea that we should demand services (no tuition fees, protected benefits) but rather than seeking a way to contribute to paying for these services personally try to push the payment for them onto a small fraction of the population. If you demand more money for X but don’t expect to pay any more for it then frankly I don’t think you’re committed to the idea.

Nov 03 2010

Book review: The Scientific Revolution and the Origins of Modern Science by John Henry

The book I review in this post is “The Scientific Revolution and the Origins of Modern Science” by John Henry. In contrast to previous history books I have read this is neither popular history of science, nor original material but instead an academic text book. My first impressions are that it is a slim volume (100 pages) and contains no pictures! Since childhood I have tended towards the weightier volume, feeling it better value for money.

The book I review in this post is “The Scientific Revolution and the Origins of Modern Science” by John Henry. In contrast to previous history books I have read this is neither popular history of science, nor original material but instead an academic text book. My first impressions are that it is a slim volume (100 pages) and contains no pictures! Since childhood I have tended towards the weightier volume, feeling it better value for money.

The Scientific Revolution is a period in European history during which the way in which science was done changed dramatically. The main action took place during the 17th century with lesser changes occurring in the 15th and 18th centuries. The Royal Society, on which I have blogged several times, plays a part in this Revolution and God’s Philosophers by James Hannam is one view of the preamble to the period.

The book starts with a brief introduction to historiography (methods of history research) of the Scientific Revolution, with a particular warning against “whiggish” behaviour: that’s to say looking back into the past and extracting from it that thread that leads to the future, ignoring all other things – the preferred alternative being to look at a period as a whole in its own terms. History as introduced by scientists is often highly whiggish.

Next up is a highlighting of the Renaissance, a period immediately prior to the Scientific Revolution wherein much renewed effort was made to learn from the Classics, the importance of the Renaissance appears to have been in initiating a break from the natural philosophy and theology taught in the universities of the time, which were teaching rather than research institutions.

The Scientific Revolution introduced two “methods of science” which differentiated it from the previous studies of natural philosophy: mathematisation and experiment. Mathematisation in that for sciences particularly relating to physics the aim became to develop a mathematical model for the physical behaviour observed. Prior to the Revolution mathematics was seen almost as a menial craft, inferior to both natural philosophy and theology which relied on logical chains of deduction to establish causes. These days mathematics has a far higher prestige, as illustrated in this xkcd comicstrip. The second element of experimentation means the use of controlled experimentation rather than pure thought to determine true facts.

One of the more surprising insights for me was the influence of magic on the developing science, very much in parallel to the influence of alchemy on the developing chemical sciences: magic was a physical equivalent. Magicians were intensely interested in the mysterious properties of physical objects and were early users of lenses and mirrors. The experience they developed in manipulating physical objects was the equivalent of the experience the alchemists gained in manipulating chemicals. Some of this thinking went forward into the new science the remaining rump of bonkers stuff left behind.

It’s very easy to glibly teach of forces and atoms to students, or perhaps blithely demonstrate the solution to an, on the face of it, tricky integral. However, we take a lot for granted: the great names of the past were at least as intelligent as more recent ones such as Einstein or Maxwell yet they struggled greatly with the idea of a force acting at a distance and so forth and that’s because these ideas are actually not obvious except in retrospect. Mechanical philosophies of Descartes and Hobbes were amongst the competing ideas for a “system of the world” ultimately supplanted by Newton.

Henry highlights that most of the participants in the Scientific Revolution were religiously devout, as were many in that time. An interesting idea taken up, but now apparently rejected, was that Puritanism was essential in driving the Scientific Revolution in Britain. Despite this, it was in this period that atheism started to appear.

A few times Henry refers to differences in emphasis between the developing new science in Britain when compared to the Continent. In Britain the emphasis was on an almost legalistic approach with purportedly bare facts presented to a jury in the form, for example, of the fellows of the Royal Society – theorising was in principle depreciated. This approach originates with Francis Bacon, a former Attorney General and experienced legal figure. On the Continent the emphasis was different, experiments were seen more as a demonstration of the correctness of a theory. The reason for this difference is laid at the door of the English Civil War, only briefly passed when the Royal Society was founded. It is argued that this largely non-confrontational style arose from a need for a bit of peace following the recent turmoil.

In sum I found this book an interesting experience: it’s very dense and heavily referenced. Popular history of science tends to revolve around individual biography and it’s nice to get some context for these lives. I’m particularly interested in following up some of the references to other European learned societies.

Further Reading

The book provides a list of handy links to online resources:

- Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy

- Prof. Robert A. Hatch’s Scientific Revolution Website

- Prof. Paul Halsall’s Scientific Revolution Website

- SparkNotes Study Guide on the Scientific Revolution

- The Robert Boyle Project

- The Galileo Project

- The Newton Project

- The MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive

These all look interesting, and although not polished I’ve been using the MacTutor for many years.