Author's posts

Oct 24 2023

Rosetta Stone – Python

In an earlier blog post I explained the motivation for a series of “Rosetta Stone” posts which described the ecosystem for different programming languages. This post covers Python, the associated GitHub repository is here. This blog post aims to provide some discussion around technology choices whilst the GitHub repository provides details of what commands to execute and what files to create.

For Python my knowledge of the ecosystem is based on considerable experience as a data scientist working predominantly in Python rather than a full-time software developer or a computer scientist. Although much of what I learned about the Python ecosystem was as a result of working on a data mesh project as, effectively, a developer.

About Python

Python is a dynamically typed language, invented by Guido van Rossum with the first version released in 1991. It was intended as a scripting language which fell between shell scripting and compiled languages like C. As of 2023 it is the most popular language in the TIOBE index, and also on GitHub.

How is Python defined?

The home for Python is https://www.python.org/ where it is managed by the Python Software Foundation. The language is defined in the Reference although this is not a formal definition. Python has a regular release schedule with a new version appearing every year or so and a well-defined life cycle process. As of writing (October 2023) Python 3.12 has just been released. In the past the great change was from Python 2 to Python 3 which was released in December 2008 – this introduced breaking changes. The evolution of the language is through the PEP (Python Enhancement Proposal) – PEP documents are an excellent resource for understanding new features.

Python Interpreters

The predominant Python interpreter is CPython which is what you get if you download Python from the official website. Personally, I have tended to use the Anaconda distribution of Python for local development. I started doing this 10 years or so ago when installing some libraries on Windows machines was a bit tricky and Anaconda made it possible/easy. It also has nice support for virtual environments – in particular it allows the Python version for the virtual environment to be defined. However, I keep thinking I should review this decision since Anaconda includes a lot of things I don’t use, they recently changed their licensing model which makes it more difficult to use in organisations and the issues with installing libraries are less these days.

CPython is not the only game in town though, there is Jython which compiles Python to Java-bytecode, IronPython which compiles it to the .NET intermediate language, and PyPy which is written in Python. These alternatives generally have the air of being interesting technical demonstrations rather than fully viable alternatives to CPython.

Typically I invoke Python scripts using a command line in Git Bash like:

./my_script.py

This works because I start all of my Python scripts with:

#!/usr/bin/env python

More generally Python scripts are invoked like:

python my_script.py

Package/Library Management

Python has always come with a pretty extensive built-in library – “batteries included” is how it is often described. I am a data scientist, and rather harshly I often judge programming languages as to whether they include a built-in library for reading and writing CSV files (Python does)!

The most common method for managing third party libraries is the `pip` package. By default this installs packages from the Python Package Index repository. The Anaconda distribution includes the `conda` package manager, which I have occasionally used to install tricky packages, and there are `pipenv` and `poetry` tools which also handle virtual environments as well as dependencies.

With pip installing a package is done using a command like:

pip install scikit-learn

If required a specific version can be specified or a version newer than a specific version. A list of dependencies can be installed from a plain text file:

pip install -r requirements.txt

The dependencies of a project are defined in the `pyproject.toml` file which configures the project. These are often described as being abstract – i.e. they indicate which packages are required, and perhaps version limits, if the host project requires functionality only available after a certain limit. The `requirements.txt` file is often found in projects, this should be a concrete specification of package versions on the developer machine. It is the “Works for me(TM)” file. I must admit I only understood this distinction after looking at the node.js package manager, npm, where the `pyproject.toml` equivalent is updated when a new package is installed. The `requirements.txt` file, equivalent – `package-lock.json` – is updated with the exact version of a package actually installed.

In Python local code can be installed as a package like:

pip install -e .

This so called “editable” installation means that a package can be used elsewhere on the same machine whilst keeping up to date with the latest changes to the code.

Virtual environments

Python has long supported the idea of a “virtual environment” – a project level installation of Python which largely isolates it from other projects on the same machine by installing packages locally.

This very nearly became mandatory, see PEP-0704 – however, virtual environments don’t work very well for certain use cases (for example continuous development pipelines) and it turns out that `pip` sits outside the PEP process so the PEP had no authority to mandate a change in `pip`!

The recommended approach to creating virtual environments is the built-in `venv` library. I use the Anaconda package manager since it allows the base version of Python to be varied on a project by project basis (or even allowing multiple versions for the same project). virtualenv, pipenv and poetry are alternatives.

IDEs like Visual Code allow the developer to select which virtual environment a project runs in.

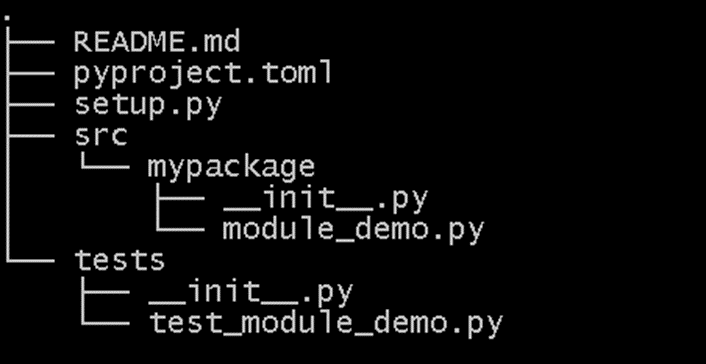

Project layout for package publication

Tied in with the installation of packages is the creation and publication of packages. This is quite a complex topic, and I wrote a whole blog post on it. Essentially Python is moving to a package publication strategy which stores all configuration in a `pyproject.toml` file (toml is a simple configuration file format) rather than an executable Python file (typically called setup.py). This position has evolved over a number of years, and the current state is still propagating through the ecosystem. An example layout is shown below, setup.py is a legacy from former package structuring standards. The __init__.py files are an indication to Python that a directory contains package code.

Testing

Python has long included the `unittest` package as a built-in package – it is inspired the venerable JUnit test library for Java. `Pytest` is an alternative I have started using recently which has better support for reusable fixtures and a simpler, implicit syntax (which personally I don’t like). Readers will note that I have a tendency to use built-in packages where at all possible, this is largely to limit the process of picking the best of a range of options, and hedging against a package falling into disrepair. Typically I use Visual Code to run tests which has satisfying green tick marks for passing tests and uncomfortable red crosses for failing tests.

Integrated Development Environments

The choice of Integrated Development Environment is a personal one, Python is sufficiently straightforward that it is easy to use a text editor and commandline to complete development related tasks. I use Microsoft Visual Code, having moved from the simpler Sublime Text. Popular alternatives are the PyCharm IDE from JetBrains and the Spyder editor. There is even a built-in IDE called IDLE. The Jupyter Notebook is used quite widely particularly amongst data scientists (personally I hate the notebook paradigm, having worked with it extensively in Matlab) but this is more suited to exploratory data analysis and visualisation than code development. I use IPython, a simple REPL, a little to confirm syntax.

Static Analysis and Formatting Tools

I group static analysis and formatting tools together because for Python static analysers tend to creep into formatting. I have started using static analysis tools and a formatter since using Visual Code whose Python support builds it in, and using development pipelines when working with others. For static analysis I use a combination of pyflakes and pylint which are pretty standard choices, and for formatting I use black.

For Python a common standard for formatting is PEP-8 which describes the style used in the Python built-in library and C codebase.

Documentation Generation

I use sphinx for generating documentation, the process is described in detail this blog post. There is a built-in library, pydoc, which I didn’t realise existed! Doxygen, the de facto standard for C++ documentation generation will also work with Python.

Type-hinting

Type-hinting was formally added to Python in version 3.5 in 2015, it allows tools to carry out static analysis for compliance with the type-hints provided but is ignored by the interpreter. I wrote about this process in Visual Code in this blog post. I thought that type-hinting was a quirk of Python but it turns out that a number of dynamically typed languages allow some form of type-hinting, and TypeScript is a whole new language which adds type-hints to JavaScript.

Wrapping up

In writing this blog post I discovered a couple of built-in libraries that was not currently using (pydoc and venv). In searching for alternatives I also saw that over a period of a few years packages go in and out of favour, or at least support.

I welcome comments, probably best on Mastodon where you can find me here.

Oct 24 2023

A Rosetta Stone for programming ecosystems

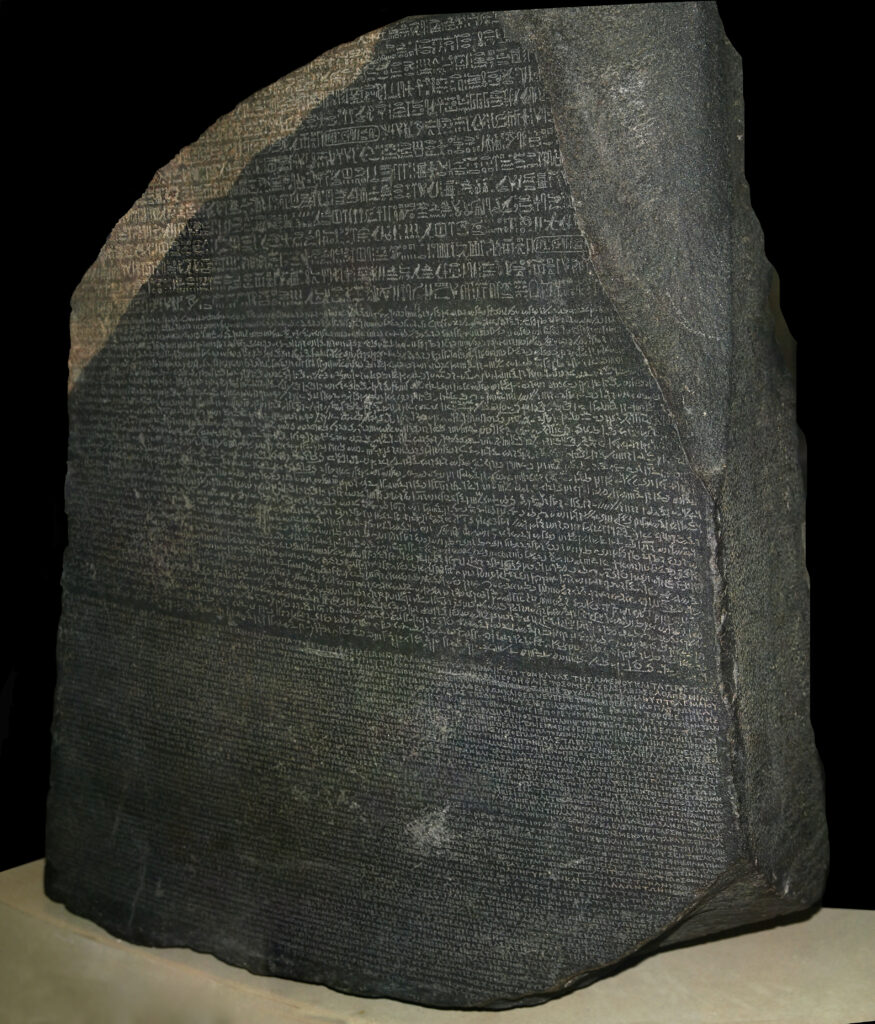

The Rosetta Stone is a stone slab dating to 196BC on which is written the same decree in three different ancient Egyptian languages, it was key to deciphering these languages in the modern era.

It strikes me that learning a new programming language is not really an exercise in learning the syntax of a new language, for vast swathes of languages those things are very similar. For an experienced programmer the learning is in the ecosystem. What we need is a Rosetta Stone for software development in different languages that tells us which tools to use for different languages, or at least gives us a respectable starting point.

To my mind the ecosystem specific to a programming language includes the language specification and evolution process, compiler/interpreter options, package/dependency management, virtual environments, project layout, testing, static analysis and formatting tools, and documentation generation. Package management, virtual environments and project layout are inter-related, certainly in Python (my primary programming language).

In researching these tools I was curious about their history. Compilers have been around since nearly the beginning of electronic computing in the late forties and early fifties. Modern testing frameworks generally derive from SmallTalk’s sUnit – published in 1989. Testing clearly went on prior to this – I am sure it is referenced in The Mythical Man Month and Grace Hopper is cited for her work in testing components and computers.

I tend to see package/dependency management as being the system by which I install packages from an internet repository such as Python’s PyPI repository – in which case the first of these was CPAN, for the Perl language first online in 1995, not long after the birth of the World Wide Web.

Separate linters date back, to 1978. Indent was the first formatter, written in 1976. The first documentation generation tools arose towards the end of the eighties (link) with JavaDoc which I suspect inspired many subsequent implementations appearing in the mid-nineties.

Tool choices are not as straightforward as they seem, in nearly all cases there are multiple options as a result of an evolution in the way programming is done more generally, or developers seeking to improve what they see as pain points in current implementations. Some elements are down to personal choice.

For my first two Rosetta Stone blog posts I look at Python and TypeScript. My aim is that the blog post will discuss the options and a GitHub repository will demonstrate one set of options in action. I am guided by my experience of working in a team on a Python project where we needed to agree a tool set and best practices. The use of development pipelines which run linters, formatters and tests automatically before code changes are merged, drove a lot of this work. The aim of these blog posts is, therefore, not to simply get an example of a programming language running but to create a project that software developers would be content to work with. The code itself is minimal, although I may add some more involved code in future.

I wrote the TypeScript in my “initial release” to see how the process would work for a language with which I was not familiar – it helped me understand the Python ecosystem better and gave me “feature envy”!

I found myself referencing numerous separate blog posts in writing these first two blog posts which suggests this Rosetta Stone is a worthwhile exercise. I also found my search results were not great, contaminated by a great deal of poorly written perhaps automatically generated material.

There are other, generic, parts of the ecosystem such as the operating system on which the code will run, the source control system and the Integrated Development Environment the developer uses which I will not generally discuss. I work almost exclusively on Windows but I prefer Git Bash as my shell. I use git with GitHub for source control and Visual Code as my editor/IDE.

When I started this exercise I thought that that there may be specific Integrated Development Environments used for specific languages. In the eighties and nineties when you bought a programming language the Integrated Development Environment was often part of the deal. This seems not to be the case anymore, most IDEs these days can be extended with plugins specific to a language so which IDE you start with is immaterial. In any case any language can be used as a combination of a text editor and command line tools.

I have been programming since I was a child in the early eighties. First in BASIC, then at university in FORTRAN, in industry in MATLAB before moving to Python. During that time I have also dabbled in C++ and Java but largely theoretical point of view. Although I have been programming for a long time it has generally been in the role of scientist / data scientist producing code for my own use, only in the last few years have I written code intended to be consumed by others.

These are my first two “Rosetta Stone” blog posts:

Oct 13 2023

Book review: Broad Band by Claire L. Evans

This review is of Broad Band by Claire L. Evans, subtitled The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet. It is arranged thematically with each chapter focusing on a couple of women moving in time from the first chapter, about Ada Lovelace in the 19th century, through to the early years of the 21st century. The first part of the book covers the early period of computing up to the mid-sixties, the second part the growth of networked computing through the seventies and eighties with the final part covering the rise of the World Wide Web and services devoted to women.

The first chapter introduces us to Ada Lovelace, sometimes heralded as the first programmer which is a somewhat disputable claim. More importantly she was clearly a competent mathematician and excelled in democratising and explaining the potential of the mechanical computing engines that Charles Babbage was trying, and largely failing, to build. More broadly this chapter covers the work of the early human “computers”, who were often women, employed to carry out calculations for astronomical or military applications. Following on from this role, by 1946 250,000 women were working in telephone exchanges (presumably in the US).

Women gained this role as “computers” for a range of reasons. In the 19th century it was seen as acceptable work for educated women whose options were severely limited – as they would be for many years to come, excepting war time. The lack of alternatives meant they were very cheap to employ. Under the cover of this apparently administrative role of “computer” women made useful, original contributions to science albeit they were not recognised as such. Women were seen as good at this type of meticulous, routine work.

When the first electronic computers were developed in the later years of the Second World War it was unsurprising that women were heavily involved in their operation partly because of their previous roles, and partly because men had been sent to fight. There appears to have been an attitude that the design and construction of such machines was men’s work and their actual use, the physical act of programming was women’s work – often neglected by those men that built the machines.

It was in this environment that the now renowned Grace Hopper worked. She started writing what we would now describe as compilers to make the task of programming computers easier. She was also instrumental in creating the COBOL programming language, reviled by computer scientist in subsequent years but comprising 80% of the world’s code by the end of the 20th century. The process that Hopper used to create the language, a committee involving multiple companies working towards a common useful goal, looks surprisingly modern.

In the sixties there was a sea-change for women in computing, it was perceived that there was a shortage of programmers and the solution was to change programming into an engineering science which had the effect of gradually pushing women out of computing through the seventies. It was at this time that the power of computer networks started to be realised.

The next part of the book covers networking via a brief diversion into mapping the Mammoth Cave system in Kentucky which became the basis of the first network computer game: Colossal Cave Adventure. I was particularly impressed by Project One, a San Francisco commune which housed a mainframe computer (a Scientific Data Systems 940) which had been blagged from a company by Pam Hardt-English. In the early seventies it became the first bulletin board system (BBS) – a type of system which was to persist all the way through to the creation of the World Wide Web (and beyond). Broad Band also covers some of the later bulletin board systems founded by women which evolved into women’s places on the Web, BBS were majority male spaces for a long time. In the meantime Resource One also became the core of the San Francisco Social Services Referral Directory which persisted through until 2009, this was a radical innovation at the time – computers used for a social purpose outside of scientific or military applications.

The internet as we know it started with ARPANET in 1969. Broad Band covers two women involved in the early internet – Elizabeth (Jake) Feinler who was responsible for the Resource Handbook – a manually compiled directory of computers, and their handlers, on ARPANET. This evolved, under her guidance, to become the WHOIS service and host.domain naming convention for internet addresses. The second woman was Radia Perlman, who invented the Spanning Tree Protocol for ethernet whilst at DEC in 1984.

This brings us, in time, to the beginning of the World Wide Web. The World Wide Web grew out of the internet. Hypertext systems had been mooted since the end of the Second World War but it wasn’t until the eighties that they became technically feasible on widely available hardware. Broad Band cites British Wendy Hall and Cathy Marshall at Rank Xerox as contributors to the development of hypertext systems. These were to be largely swept away by Tim Berners-Lee’s HTML format which had the key feature of hyperlinking across different computers even if this made the handling of those links prone to decay – something handled better by other non-networked hypertext systems. The World Wide Web grew ridiculously quickly in the early nineties. Berners-Lee demonstrated a rather uninspiring version at HyperText ’91 and by HyperText ’94 he was keynote speaker.

There is a a brief chapter devoted to women in gaming. Apparently Barbie Fashion Designer sold 600,000 units in 1996 more than Doom and Quake! There was a brief period when games were made very explicitly for girls – led to a degree by Brenda Laurel who had done extensive research showing boys strive for mastery in games, whilst girls were looking for a collaborator to complete a task. These ideas held sway for a while before a more diverse gaming market took hold which didn’t divide games so much by gender.

It is tempting for me to say that where women have made their mark in computing and the internet is in forming communities, communicating the benefits of technology and making them easier to use – in a reprise of the early pioneering women in science – because that is what women are good at. However, this is the space in which women have been allowed by men – it is not a question of innate ability alone.

I found this book really interesting, it is more an entry point into the topic of women in computing than a comprehensive history. It has made me nostalgic for my computing experiences of the eighties and nineties, and I have added a biography of Grace Hopper to my reading list.

Sep 26 2023

Book review: The First Astronomers by Duane Hamacher

My next review is of First Astronomers: How Indigenous Elders read the stars by Duane Hamacher. It is fair to say that Western astronomers, and other Western scientists have not treated Indigenous populations, and their knowledge, with a great deal of respect. Even now astronomers are in dispute with Indigenous populations in Hawaii over the siting of telescopes. In this book Hamacher tries to redress this imbalance and in my view does a good job of treating his interviewees, and their knowledge, with respect.

Western astronomers are not alien to interacting with people outside their professional group as part of their research most notably using historical data, like Chinese records of supernova but also amateur observers play an important in modern astronomy – particularly in the observation of comets and the like and other transient phenomena accessible using modest equipment.

The book starts with a prologue describing the background to the book and introducing a number of the Indigenous people who contributed, in the longer frontspiece they are listed as co-authors. They are largely from Australia but there are references to New Zealand, North American Native Americans, Artic peoples, South American and Africa groups.

Hamacher is an astronomer by profession and this has a bearing on this interviews with Indigenous Elders. In the past anthropologists have talked to Elders about their star knowledge and a lack of astronomical knowledge has led to mis-interpretation. I was intrigued to learn that in Western mythology the star name “Antares” is derived from the greek “anti Mars” – since Mars and Antares, in the same part of the sky and with a reddish hue are often confused!

The book is then divided thematically into chapters relating to different sorts of stars (including the moon). These are The Nearest Star (the sun), The Moon, Wandering Stars (planets), Twinkling Stars, Seasonal Stars, Variable Stars, Cataclysmic Stars (supernova and the like), Navigational Stars and Falling Stars (meteors and craters).

The big difference a Western reader will see is that Indigenous knowledge is transmitted via oral traditions, incorporating song and dance. Oral traditions are about creating a story around some star locations that provide useful information like where and when to hunt a particular animal or plant a particular crop, or where you are and how to get to where you want to be . The story linked to the stars allows it to be transmitted to the next generation without error. They are mnemonics rather than an attempt to describe a factual truth. This is obvious in Indigenous oral traditions which are still alive but I suspect it would have been the case for the oral traditions of Western Europe which give us our modern constellations.

Oral traditions can be very powerful, there is a group of craters in Australia (the Henbury Craters) which were created by a meteor impact around 4200 years ago – Aboriginal oral traditions have held this knowledge of their creation across that period of time.

Indigenous constellations can overlap and change through the seasons, they also incorporate dark space – particularly in the Milky Way. These constellations are locally determined to fit with local conditions, and land features used as landmarks.

As well as maritime navigation where the stars are used directly for finding direction, the stars are also used as a navigational aid for terrestrial travel – the routes are learnt in the dark of the winter using the stars as a map of the ground (picking stars which approximate the locations on the ground). These “songlines” are reflected in some modern day highways in Australia.

What comes through from the book is that Indigenous astronomers were very astute observers of the sky, noting phenomena including the varying twinkle of stars (including colour and intensity variations), the 8 year period of Venus returning to the same location in the sky, variable stars, sunspots and their 11 year cycle, the sounds associated with aurora and so forth. Some of these phenomena were not widely recognised by astronomers in the West until into the 19th century. In addition they had a clear understanding of many phenomena: that the moon reflected the light of the sun, that the earth was a sphere, that craters were the result of rocks falling from the sky.

Unsurprisingly, I was constantly comparing with Western astronomy. The great divergence was sometime around the end of the 16th century when Western astronomers started making detailed written records of the locations of stars and planets and using mathematics to understand them, and then moved on to the use of telescopes. I can’t help feeling the Indigenous people were held back by a lack of writing.

What comes through at the end of the book is that in the Indigenous communities have a long history of passionate and astute astronomers, dedicated to their role, and increasingly they are taking part and excelling in Western astronomy and astrophysics.

Sep 08 2023

Book review: Foreign Bodies: Pandemics, Vaccines and the Health of Nations by Simon Schama

My next review is of Foreign Bodies: Pandemics, Vaccines and the Health of Nations by Simon Schama.

The book is divided into three parts, covering smallpox, cholera and bubonic plague – in its late 19th century manifestation – and how vaccines were developed and deployed for these diseases. Waldemar Haffkine features heavily in the chapters on cholera and bubonic plague, for which he invented and delivered vaccines, and in some senses this is his biography albeit somewhat unfocussed with much additional material.

The first part covers the introduction of inoculation for smallpox to Western Europe in the early 18th century. This a process whereby a small quantity of the material from a smallpox pustule is introduced to small cuts in the skin of a patient who then falls mildly ill with the disease but is protected from further more serious infection. Voltaire appears in this section as a hook for some of the discussion – he was one of the early promoters of inoculation in France.

Terms are a bit fluid in this area but inoculation refers to the use of the live, unaltered bacteria/virus whilst vaccination refers to the use of a vaccine which is based on a weakened or even partial version of the disease causing micro-organism.

Smallpox was a serious disease in the 18th century, having apparently mutated to a more virulent, deadly form in the mid-17th century. This newer variant killed as many as 1 in 6 of those infected with many of those surviving showing significant scarring. It was indiscriminate, killing royalty as well as paupers. The inoculation process had been used by at least some communities in the Middle East, Africa and South America. The first chapter in this section is largely about the introduction of the idea of inoculation to polite Western European society. This met with some resistance – inoculation did not fit with the then current model of the smallpox disease (essentially the side effect of a bodily purging process), and it challenged the medical establishment coming as it did from a “foreign” country and, worse than that, was often practiced by women!

The second of the smallpox chapter covers the commercialisation of the inoculation process during the 18th century. This typically involved upselling preliminary treatments and post-inoculation care which was largely superfluous. It is interesting though that as part of this process the first clinical trials were conducted to test the efficacy of the process.

The second part of the book, on cholera, features Adrien Proust, father of Marcel Proust. Adrien Proust would become very involved in creating international the first public health organisations. Cholera had come to Europe around 1817 with pandemics killing many thousands recurring through the century. Proust senior had been a young doctor in the 1854 outbreak in Paris as a hospital doctor he would have seen 40% of patients die from this disease. At the time the cause of cholera was not known, it was assumed that it was a result of “filth” and unsanitary living conditions. This perhaps explains some of the Victorian efforts to install sewers and water systems, as well as the fact that living in crowded insanitary cities was simply unpleasant.

In the case of cholera, which is a bacterial infection discovered (quietly) by Filippo Pacini in 1854 and more famously by Robert Koch in 1883, sanitation and disinfection measures are a reasonable approach which has some benefits. There was commercial opposition to seeing cholera as an infection because that implied quarantines and the like which had a commercial impact. This attitude was to recur in the subsequent bubonic plague outbreaks in Indian and China which has more serious consequences since dirty water has no bearing on plague transmission. In fact we saw this argument regarding the COVID-19 restrictions.

It is in this part we first meet Waldemar Haffkine, born into a Jewish family in Odessa in 1860. He trained as a biologist working under Ilya Mechnikov, who would later win a Noble Prize for his work on immunity. Haffkine went on to the Pasteur Institute in Paris (Pasteur was still alive at this point), where he developed a vaccine for cholera. Haffkine had a an extensive file with the authorities in Odessa as a result of his activism in the defence of the Jewish community against repeated pogroms.

He tested his vaccine in India with minimal support from the colonial medical services. Reading between the lines it looks like his expenses claims were a key historical resource. To a degree he used the Indian population as one amenable for doing controlled trials of the vaccine due to their living conditions, and their status in the colonial system.

The part of the book on bubonic plague is a repeat of the chapters on cholera with Haffkine involved in the discovery of the plague bacillus, and the development and deployment of the vaccine, particularly in India. Here the story diverges a bit, the colonial response to plague was to apply sanitation measures up to and including burning down houses where infections had occurred. This, naturally, angered the local population and played some part in the rise of Indian nationalism.

Haffkine’s medical career was to effectively come to an end in the Indian plague vaccination programme. A vial of vaccine that had been produced in the facility he led was contaminated with tetanus leading to the death of nineteen vaccine recipients. The colonial Indian medical authorities were quick to place the blame on Haffkine although later investigations showed that the vial was most likely contaminated “in the field” (literally) and so was not at all Haffkine’s responsibility. He was eventually notationally exonerated with the support of Sir Ronald Ross (who won a Noble prize for his work on the transmission of malaria) but the damage was done and after some work on a typhoid vaccine he gave up his medical work aged 54.

Haffkine, in his later years, returned to his Jewish roots – arguing the case for Orthodox Judaism, and supporting a movement to make Crimea an area for training Jews in agriculture with a view to moving to Palestine. After the Russian revolution Jews no longer faced pogroms on the basis of their religion, they experienced persecution because the Soviet Union did not want anyone, regardless of religion practicing their religion.

I have mixed feelings about this book, it feels like it is trying to be several things at once – a history of vaccination for smallpox, cholera and bubonic plague but also a biography of Waldemar Haffkine with substantial chunks of not entirely relevant material also added. The long chapters don’t suit my reading style very well. At one point Schama manages a half-page sentence which I don’t think I’ve seen before in English! The book is clearly well-researched and written with some style but it doesn’t feel like a book to be read by the pool.