|

| Triarthrus eatoni from Beechers Trilobite bed |

This week I’m reporting on “Trilobite! Eye witness to evolution” by Richard Fortey, which I came to via Attenborough’s “First Life” TV programme and advice from @crafthole. As usual this is intended as part notes for my own edification and part review. I read the Kindle version of this book, I’d recommend getting the paper version since the publishers have made no effort to incorporate any of the illustrations from the book into the electronic edition.

Fortey has a rather literary style which makes for rather pleasing reading: the book starts with a walk along the cliffs beyond Boscastle to a location used by Thomas Hardy in “A pair of blue eyes” where the hero comes face to face with a trilobite embedded in the cliffs. The book covers the discovery of trilobite anatomy; evolution, the drifting continents and what makes a palaeontologist tick.

Trilobites were common in the relatively early history of life on earth, during the Cambrian period, about 500 million years ago and became extinct at the end of the Permian period about 250 million years ago. The book starts with a description of trilobite anatomy – you can see the details on the wikipedia page. The basic fossil remnants are the hard shell of the trilobite, the upper surface shield – the closest living relatives to trilobites are things like woodlice and the horseshoe crab (which Fortey eats in Thailand!). Generally legs and soft parts do not fossilise, so it was some time before these structures were understood.

The first written record of a trilobite was by Dr Lhwyd in a letter to Martin Lister, reported to the Royal Society in 1699. It is a fleeting mention, and he mis-identifies his find as a “skeleton of some flat fish”, noting that they are abundant but his illustration is quite clearly of a trilobite. Dr Lhwyd writes from Wales and much of the early history of the trilobite’s discovery is tied up with Wales, trilobites are characteristic of the Cambrian period, named after Wales.

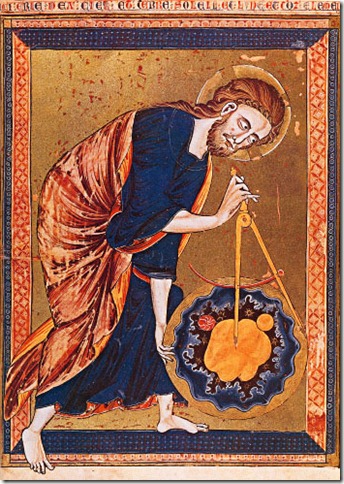

The image at the top of this post illustrates the discovery of trilobite legs. Most trilobites lost their legs in the fossilisation process, they are flimsy and poorly armoured. However in the case of the Beechers’ trilobite bed special preservation circumstances have fossilised the legs, in this case picked out in ‘fools gold’ or iron pyrite.

I was rather impressed by the chapter on trilobite eyes, as reported in my post on First Life, trilobite eyes are made from calcite – an array of calcite hexagonal prisms in the eye channels light to light receptors. Calcite is birefringent, one of the features of this property is that light only travels along the prisms to the light sensors if it enters them square on. So the relatively large number of calcite prisms in trilobite eyes suggest resolution comes from directional selectivity of the prisms. Some trilobite eyes are more complex than this: the Phacops eye is comprised of fewer prisms but with cunning lenses at the outside faces which work using magnesium concentration gradients to eliminate chromatic aberration – this suggests they channel light to multiple light receptors. Calcite is calcium carbonate, but the calcium can be selectively replaced by magnesium which changes it’s optical properties – in terms of man-made optics this type of thing is feasible but it’s pretty sophisticated. Reading this on the train the temptation to grab fellow commuters and jab my finger at the appropriate paragraph shouting “Have you read this about trilobite eyes, it is flippin’ incredible!!” was almost overwhelming!

Fortey is clearly passionate about his topic, as he says of breaking rocks to find the trilobites therein:

“Hardened criminals used to be required to do the same thing before it was banned as inhumane. I loved it.”

He works as a palaeontologists tasked with identifying trilobites, and if necessary creating new species. I learnt that the Linnean binomial system is slightly more complex than I thought, as well as having a two part name each species is tagged with the name of the person who first described a species this helps the expert in the field trace the original citation for a species. You gain the impression of someone able to identify one trilobite of a myriad potential species from mere fragments, in the manner of those archaeologists who can apparently build a pot, complete with its history, from a tiny shard. As arthropods with tough exoskeletons, trilobites moulted their shells to grow – each animal strewing the landscape with potential fossil fragments: fossil factories, Fortey calls them. He goes into some detail of the inferred life styles of trilobites and their development i.e how juveniles grow into adults. For some of the developmental stuff it would be nice to see the supporting fossils: it sounds ferociously difficult separating juvenile forms from different species of trilobite.

The large variety of trilobites, and their appearance in the early days of fossilising life, makes them a useful tool in the study of how evolution operates. Fortey rebuts the proposal by Stephen Jay Gould in “Wonderful Life” for a Cambrian explosion producing massive diversity of forms, beyond what we see now. Arguing from research by former colleagues that the variation in forms discovered in the Burgess Shale is much smaller than Gould claims. The difference being in the interpretation of how diverse forms are from relatively indistinct fossils. This is perhaps a warning to the casual reader that controversies are easily hidden in the popular science literature.

A second application of trilobites is in the dating of rocks: they are very common, fossilise well and, over a period of time, evolved into many distinctive forms which makes them ideal for the purpose. Finally they can also be used in the reconstruction of ancient continents: identifying common collections of trilobites in disparate parts of the world suggests they were originally found in one place.

As mentioned at the top of page, my Kindle edition of this book was bereft of illustrations but by the power of google, I can give you phacops, famous for it’s fancy eyes, ollenelus – one of the commonest of the early trilobites, calymene blumenbachii pleasingly convex as Fortey says, paradoxides another early species, Ogygiocarella debuchii as discovered by Dr Lhywd.

I found this book most useful as an insight into the mind of a palaeontologist and a taxonomist.

Further reading

An overview of trilobites

A piece by Fortey in American Scientist on trilobites (pdf)