In an earlier blog post I explained the motivation for a series of “Rosetta Stone” posts which described the ecosystem for different programming languages. This post covers Python, the associated GitHub repository is here. This blog post aims to provide some discussion around technology choices whilst the GitHub repository provides details of what commands to execute and what files to create.

For Python my knowledge of the ecosystem is based on considerable experience as a data scientist working predominantly in Python rather than a full-time software developer or a computer scientist. Although much of what I learned about the Python ecosystem was as a result of working on a data mesh project as, effectively, a developer.

About Python

Python is a dynamically typed language, invented by Guido van Rossum with the first version released in 1991. It was intended as a scripting language which fell between shell scripting and compiled languages like C. As of 2023 it is the most popular language in the TIOBE index, and also on GitHub.

How is Python defined?

The home for Python is https://www.python.org/ where it is managed by the Python Software Foundation. The language is defined in the Reference although this is not a formal definition. Python has a regular release schedule with a new version appearing every year or so and a well-defined life cycle process. As of writing (October 2023) Python 3.12 has just been released. In the past the great change was from Python 2 to Python 3 which was released in December 2008 – this introduced breaking changes. The evolution of the language is through the PEP (Python Enhancement Proposal) – PEP documents are an excellent resource for understanding new features.

Python Interpreters

The predominant Python interpreter is CPython which is what you get if you download Python from the official website. Personally, I have tended to use the Anaconda distribution of Python for local development. I started doing this 10 years or so ago when installing some libraries on Windows machines was a bit tricky and Anaconda made it possible/easy. It also has nice support for virtual environments – in particular it allows the Python version for the virtual environment to be defined. However, I keep thinking I should review this decision since Anaconda includes a lot of things I don’t use, they recently changed their licensing model which makes it more difficult to use in organisations and the issues with installing libraries are less these days.

CPython is not the only game in town though, there is Jython which compiles Python to Java-bytecode, IronPython which compiles it to the .NET intermediate language, and PyPy which is written in Python. These alternatives generally have the air of being interesting technical demonstrations rather than fully viable alternatives to CPython.

Typically I invoke Python scripts using a command line in Git Bash like:

./my_script.py

This works because I start all of my Python scripts with:

#!/usr/bin/env python

More generally Python scripts are invoked like:

python my_script.py

Package/Library Management

Python has always come with a pretty extensive built-in library – “batteries included” is how it is often described. I am a data scientist, and rather harshly I often judge programming languages as to whether they include a built-in library for reading and writing CSV files (Python does)!

The most common method for managing third party libraries is the `pip` package. By default this installs packages from the Python Package Index repository. The Anaconda distribution includes the `conda` package manager, which I have occasionally used to install tricky packages, and there are `pipenv` and `poetry` tools which also handle virtual environments as well as dependencies.

With pip installing a package is done using a command like:

pip install scikit-learn

If required a specific version can be specified or a version newer than a specific version. A list of dependencies can be installed from a plain text file:

pip install -r requirements.txt

The dependencies of a project are defined in the `pyproject.toml` file which configures the project. These are often described as being abstract – i.e. they indicate which packages are required, and perhaps version limits, if the host project requires functionality only available after a certain limit. The `requirements.txt` file is often found in projects, this should be a concrete specification of package versions on the developer machine. It is the “Works for me(TM)” file. I must admit I only understood this distinction after looking at the node.js package manager, npm, where the `pyproject.toml` equivalent is updated when a new package is installed. The `requirements.txt` file, equivalent – `package-lock.json` – is updated with the exact version of a package actually installed.

In Python local code can be installed as a package like:

pip install -e .

This so called “editable” installation means that a package can be used elsewhere on the same machine whilst keeping up to date with the latest changes to the code.

Virtual environments

Python has long supported the idea of a “virtual environment” – a project level installation of Python which largely isolates it from other projects on the same machine by installing packages locally.

This very nearly became mandatory, see PEP-0704 – however, virtual environments don’t work very well for certain use cases (for example continuous development pipelines) and it turns out that `pip` sits outside the PEP process so the PEP had no authority to mandate a change in `pip`!

The recommended approach to creating virtual environments is the built-in `venv` library. I use the Anaconda package manager since it allows the base version of Python to be varied on a project by project basis (or even allowing multiple versions for the same project). virtualenv, pipenv and poetry are alternatives.

IDEs like Visual Code allow the developer to select which virtual environment a project runs in.

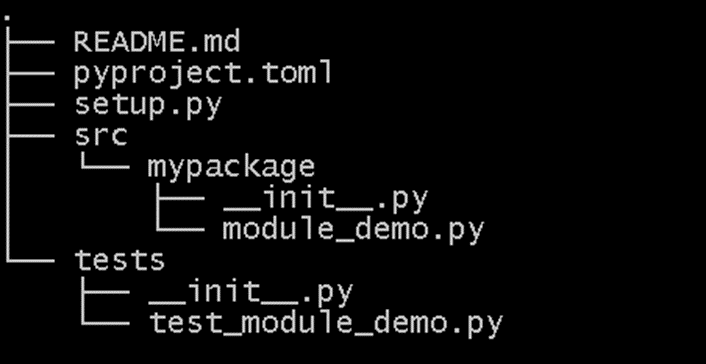

Project layout for package publication

Tied in with the installation of packages is the creation and publication of packages. This is quite a complex topic, and I wrote a whole blog post on it. Essentially Python is moving to a package publication strategy which stores all configuration in a `pyproject.toml` file (toml is a simple configuration file format) rather than an executable Python file (typically called setup.py). This position has evolved over a number of years, and the current state is still propagating through the ecosystem. An example layout is shown below, setup.py is a legacy from former package structuring standards. The __init__.py files are an indication to Python that a directory contains package code.

Testing

Python has long included the `unittest` package as a built-in package – it is inspired the venerable JUnit test library for Java. `Pytest` is an alternative I have started using recently which has better support for reusable fixtures and a simpler, implicit syntax (which personally I don’t like). Readers will note that I have a tendency to use built-in packages where at all possible, this is largely to limit the process of picking the best of a range of options, and hedging against a package falling into disrepair. Typically I use Visual Code to run tests which has satisfying green tick marks for passing tests and uncomfortable red crosses for failing tests.

Integrated Development Environments

The choice of Integrated Development Environment is a personal one, Python is sufficiently straightforward that it is easy to use a text editor and commandline to complete development related tasks. I use Microsoft Visual Code, having moved from the simpler Sublime Text. Popular alternatives are the PyCharm IDE from JetBrains and the Spyder editor. There is even a built-in IDE called IDLE. The Jupyter Notebook is used quite widely particularly amongst data scientists (personally I hate the notebook paradigm, having worked with it extensively in Matlab) but this is more suited to exploratory data analysis and visualisation than code development. I use IPython, a simple REPL, a little to confirm syntax.

Static Analysis and Formatting Tools

I group static analysis and formatting tools together because for Python static analysers tend to creep into formatting. I have started using static analysis tools and a formatter since using Visual Code whose Python support builds it in, and using development pipelines when working with others. For static analysis I use a combination of pyflakes and pylint which are pretty standard choices, and for formatting I use black.

For Python a common standard for formatting is PEP-8 which describes the style used in the Python built-in library and C codebase.

Documentation Generation

I use sphinx for generating documentation, the process is described in detail this blog post. There is a built-in library, pydoc, which I didn’t realise existed! Doxygen, the de facto standard for C++ documentation generation will also work with Python.

Type-hinting

Type-hinting was formally added to Python in version 3.5 in 2015, it allows tools to carry out static analysis for compliance with the type-hints provided but is ignored by the interpreter. I wrote about this process in Visual Code in this blog post. I thought that type-hinting was a quirk of Python but it turns out that a number of dynamically typed languages allow some form of type-hinting, and TypeScript is a whole new language which adds type-hints to JavaScript.

Wrapping up

In writing this blog post I discovered a couple of built-in libraries that was not currently using (pydoc and venv). In searching for alternatives I also saw that over a period of a few years packages go in and out of favour, or at least support.

I welcome comments, probably best on Mastodon where you can find me here.