There is a General Election being held in the UK today, along with local council elections in some parts of the country. The count will take place commencing at 10pm this evening, and the count will likely finish sometime around noon tomorrow.

Should you stay up awaiting all the results?

My advice is “no” but that’s because I’m getting old and like my sleep! My plan is to stay up for the BBC exit poll at 10:15pm and then go to bed, probably to awake with the dawn chorus at 4am.

If you do stay up then what can you expect? The Press Association list of estimated declaration times from here, they’re based on council estimates and previous declarations where the council provides no estimates. My experience is that the more interesting results are delayed beyond their estimated time.

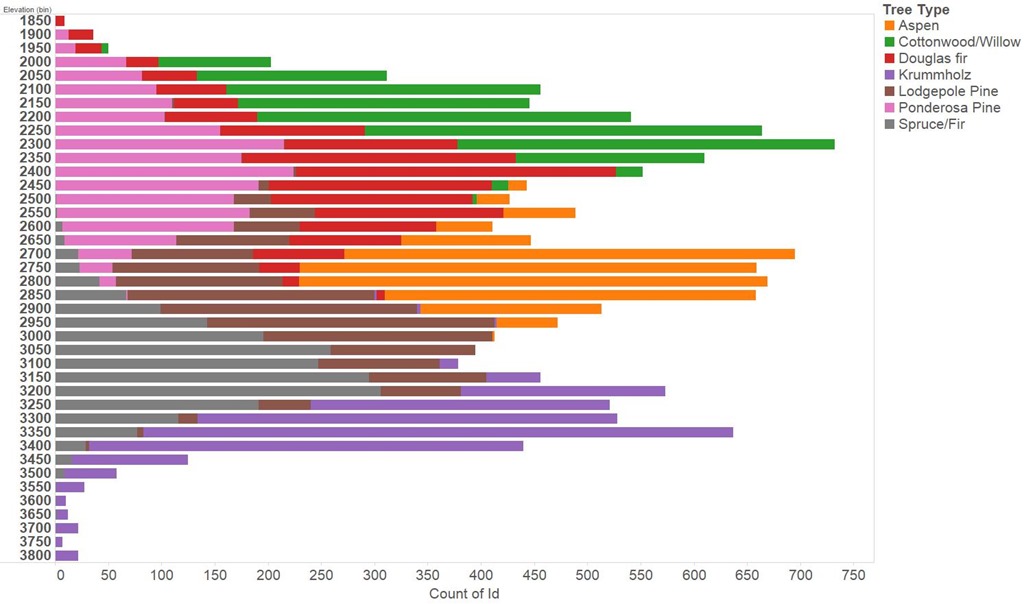

As you can see from the chart below, aside from a scattering of seats, things start to pick up around 2am. Results start to pour in around 3am and by 7am it is all over bar a few stragglers.

If you want a more narrative description of what will happen and some anticipated milestones then The Guardian has a report (here).

For the record, and for readability here is the complete list:

| 320 | Houghton & Sunderland South | 23:00 |

| 603 | Washington & Sunderland West | 23:30 |

| 551 | Sunderland Central | 00:01 |

| 216 | Durham North West | 00:30 |

| 14 | Antrim North | 01:00 |

| 175 | Dagenham & Rainham | 01:00 |

| 215 | Durham North | 01:00 |

| 255 | Foyle | 01:00 |

| 435 | Nuneaton | 01:00 |

| 176 | Darlington | 01:30 |

| 214 | Durham, City of | 01:30 |

| 221 | Easington | 01:30 |

| 347 | Lagan Valley | 01:30 |

| 407 | Na h-Eileanan an Iar | 01:30 |

| 584 | Tyrone West | 01:30 |

| 586 | Upper Bann | 01:30 |

| 588 | Vale of Clwyd | 01:30 |

| 12 | Angus | 02:00 |

| 13 | Antrim East | 02:00 |

| 28 | Barking | 02:00 |

| 38 | Battersea | 02:00 |

| 45 | Belfast East | 02:00 |

| 46 | Belfast North | 02:00 |

| 47 | Belfast South | 02:00 |

| 48 | Belfast West | 02:00 |

| 66 | Bishop Auckland | 02:00 |

| 71 | Blaenau Gwent | 02:00 |

| 106 | Broxbourne | 02:00 |

| 125 | Canterbury | 02:00 |

| 131 | Carmarthen East & Dinefwr | 02:00 |

| 132 | Carmarthen West & Pembrokeshire South | 02:00 |

| 134 | Castle Point | 02:00 |

| 139 | Chelmsford | 02:00 |

| 142 | Chesham & Amersham | 02:00 |

| 150 | Christchurch | 02:00 |

| 202 | Down North | 02:00 |

| 217 | Dwyfor Meirionnydd | 02:00 |

| 223 | East Kilbride, Strathaven & Lesmahagow | 02:00 |

| 226 | Eastleigh | 02:00 |

| 239 | Epping Forest | 02:00 |

| 250 | Fife North East | 02:00 |

| 269 | Glenrothes | 02:00 |

| 285 | Halton | 02:00 |

| 345 | Kirkcaldy & Cowdenbeath | 02:00 |

| 348 | Lanark & Hamilton East | 02:00 |

| 375 | Llanelli | 02:00 |

| 427 | Northampton North | 02:00 |

| 428 | Northampton South | 02:00 |

| 443 | Oxford East | 02:00 |

| 462 | Putney | 02:00 |

| 487 | Rutherglen & Hamilton West | 02:00 |

| 530 | Staffordshire South | 02:00 |

| 542 | Strangford | 02:00 |

| 552 | Surrey East | 02:00 |

| 562 | Tamworth | 02:00 |

| 574 | Tooting | 02:00 |

| 647 | Ynys Mon | 02:00 |

| 570 | Thornbury & Yate | 02:15 |

| 15 | Antrim South | 02:30 |

| 143 | Chester, City of | 02:30 |

| 151 | Cities of London & Westminster | 02:30 |

| 153 | Cleethorpes | 02:30 |

| 189 | Devon East | 02:30 |

| 211 | Dundee East | 02:30 |

| 212 | Dundee West | 02:30 |

| 227 | Eddisbury | 02:30 |

| 234 | Ellesmere Port & Neston | 02:30 |

| 251 | Filton & Bradley Stoke | 02:30 |

| 287 | Hampshire East | 02:30 |

| 296 | Hartlepool | 02:30 |

| 302 | Hemel Hempstead | 02:30 |

| 308 | Hertford & Stortford | 02:30 |

| 330 | Inverclyde | 02:30 |

| 334 | Islington North | 02:30 |

| 335 | Islington South & Finsbury | 02:30 |

| 342 | Kilmarnock & Loudoun | 02:30 |

| 344 | Kingswood | 02:30 |

| 359 | Leicestershire North West | 02:30 |

| 367 | Lichfield | 02:30 |

| 379 | Ludlow | 02:30 |

| 385 | Makerfield | 02:30 |

| 399 | Mitcham & Morden | 02:30 |

| 402 | Montgomeryshire | 02:30 |

| 412 | Newbury | 02:30 |

| 474 | Rochdale | 02:30 |

| 533 | Stirling | 02:30 |

| 615 | Westminster North | 02:30 |

| 621 | Wimbledon | 02:30 |

| 636 | Workington | 02:30 |

| 646 | Yeovil | 02:30 |

| 1 | Aberavon | 03:00 |

| 2 | Aberconwy | 03:00 |

| 6 | Airdrie & Shotts | 03:00 |

| 10 | Alyn & Deeside | 03:00 |

| 11 | Amber Valley | 03:00 |

| 16 | Arfon | 03:00 |

| 17 | Argyll & Bute | 03:00 |

| 29 | Barnsley Central | 03:00 |

| 30 | Barnsley East | 03:00 |

| 33 | Basildon South & Thurrock East | 03:00 |

| 41 | Bedford | 03:00 |

| 49 | Bermondsey & Old Southwark | 03:00 |

| 75 | Bolsover | 03:00 |

| 76 | Bolton North East | 03:00 |

| 77 | Bolton South East | 03:00 |

| 78 | Bolton West | 03:00 |

| 81 | Bosworth | 03:00 |

| 84 | Bracknell | 03:00 |

| 89 | Brecon & Radnorshire | 03:00 |

| 90 | Brent Central | 03:00 |

| 91 | Brent North | 03:00 |

| 100 | Bristol North West | 03:00 |

| 102 | Bristol West | 03:00 |

| 111 | Bury North | 03:00 |

| 112 | Bury South | 03:00 |

| 113 | Bury St Edmunds | 03:00 |

| 117 | Camberwell & Peckham | 03:00 |

| 130 | Carlisle | 03:00 |

| 154 | Clwyd South | 03:00 |

| 155 | Clwyd West | 03:00 |

| 156 | Coatbridge, Chryston & Bellshill | 03:00 |

| 160 | Copeland | 03:00 |

| 170 | Croydon Central | 03:00 |

| 171 | Croydon North | 03:00 |

| 172 | Croydon South | 03:00 |

| 179 | Delyn | 03:00 |

| 181 | Derby North | 03:00 |

| 182 | Derby South | 03:00 |

| 184 | Derbyshire Mid | 03:00 |

| 185 | Derbyshire North East | 03:00 |

| 186 | Derbyshire South | 03:00 |

| 209 | Dunbartonshire East | 03:00 |

| 213 | Dunfermline & Fife West | 03:00 |

| 224 | East Lothian | 03:00 |

| 241 | Erewash | 03:00 |

| 244 | Exeter | 03:00 |

| 245 | Falkirk | 03:00 |

| 256 | Fylde | 03:00 |

| 260 | Gedling | 03:00 |

| 262 | Glasgow Central | 03:00 |

| 263 | Glasgow East | 03:00 |

| 264 | Glasgow North | 03:00 |

| 265 | Glasgow North East | 03:00 |

| 266 | Glasgow North West | 03:00 |

| 267 | Glasgow South | 03:00 |

| 268 | Glasgow South West | 03:00 |

| 273 | Gower | 03:00 |

| 290 | Hampstead & Kilburn | 03:00 |

| 293 | Harrogate & Knaresborough | 03:00 |

| 298 | Hastings & Rye | 03:00 |

| 299 | Havant | 03:00 |

| 310 | Hertfordshire South West | 03:00 |

| 314 | High Peak | 03:00 |

| 316 | Holborn & St Pancras | 03:00 |

| 318 | Hornsey & Wood Green | 03:00 |

| 323 | Hull East | 03:00 |

| 324 | Hull North | 03:00 |

| 325 | Hull West & Hessle | 03:00 |

| 326 | Huntingdon | 03:00 |

| 333 | Isle of Wight | 03:00 |

| 337 | Jarrow | 03:00 |

| 343 | Kingston & Surbiton | 03:00 |

| 346 | Knowsley | 03:00 |

| 376 | Londonderry East | 03:00 |

| 386 | Maldon | 03:00 |

| 393 | Merthyr Tydfil & Rhymney | 03:00 |

| 395 | Middlesbrough South & Cleveland East | 03:00 |

| 403 | Moray | 03:00 |

| 406 | Motherwell & Wishaw | 03:00 |

| 408 | Neath | 03:00 |

| 417 | Newport East | 03:00 |

| 418 | Newport West | 03:00 |

| 421 | Norfolk Mid | 03:00 |

| 436 | Ochil & Perthshire South | 03:00 |

| 445 | Paisley & Renfrewshire North | 03:00 |

| 446 | Paisley & Renfrewshire South | 03:00 |

| 450 | Perth & Perthshire North | 03:00 |

| 451 | Peterborough | 03:00 |

| 460 | Preston | 03:00 |

| 469 | Renfrewshire East | 03:00 |

| 471 | Ribble Valley | 03:00 |

| 481 | Rother Valley | 03:00 |

| 482 | Rotherham | 03:00 |

| 486 | Rushcliffe | 03:00 |

| 513 | Skipton & Ripon | 03:00 |

| 514 | Sleaford & North Hykeham | 03:00 |

| 515 | Slough | 03:00 |

| 516 | Solihull | 03:00 |

| 517 | Somerset North | 03:00 |

| 522 | South Shields | 03:00 |

| 528 | Stafford | 03:00 |

| 535 | Stockton North | 03:00 |

| 536 | Stockton South | 03:00 |

| 540 | Stone | 03:00 |

| 550 | Suffolk West | 03:00 |

| 558 | Swansea East | 03:00 |

| 559 | Swansea West | 03:00 |

| 560 | Swindon North | 03:00 |

| 561 | Swindon South | 03:00 |

| 565 | Telford | 03:00 |

| 571 | Thurrock | 03:00 |

| 589 | Vale of Glamorgan | 03:00 |

| 608 | Wellingborough | 03:00 |

| 610 | Welwyn Hatfield | 03:00 |

| 611 | Wentworth & Dearne | 03:00 |

| 623 | Windsor | 03:00 |

| 641 | Wrexham | 03:00 |

| 642 | Wycombe | 03:00 |

| 643 | Wyre & Preston North | 03:00 |

| 8 | Aldridge-Brownhills | 03:30 |

| 35 | Bassetlaw | 03:30 |

| 40 | Beckenham | 03:30 |

| 42 | Bedfordshire Mid | 03:30 |

| 44 | Bedfordshire South West | 03:30 |

| 69 | Blackpool North & Cleveleys | 03:30 |

| 70 | Blackpool South | 03:30 |

| 72 | Blaydon | 03:30 |

| 82 | Bournemouth East | 03:30 |

| 83 | Bournemouth West | 03:30 |

| 104 | Bromley & Chislehurst | 03:30 |

| 109 | Burnley | 03:30 |

| 121 | Cambridgeshire North West | 03:30 |

| 122 | Cambridgeshire South | 03:30 |

| 136 | Charnwood | 03:30 |

| 141 | Cheltenham | 03:30 |

| 164 | Cotswolds, The | 03:30 |

| 201 | Dover | 03:30 |

| 203 | Down South | 03:30 |

| 206 | Dulwich & West Norwood | 03:30 |

| 210 | Dunbartonshire West | 03:30 |

| 222 | East Ham | 03:30 |

| 233 | Edmonton | 03:30 |

| 237 | Enfield North | 03:30 |

| 238 | Enfield Southgate | 03:30 |

| 272 | Gosport | 03:30 |

| 276 | Great Grimsby | 03:30 |

| 292 | Harlow | 03:30 |

| 368 | Lincoln | 03:30 |

| 369 | Linlithgow & Falkirk East | 03:30 |

| 374 | Livingston | 03:30 |

| 377 | Loughborough | 03:30 |

| 396 | Midlothian | 03:30 |

| 419 | Newry & Armagh | 03:30 |

| 442 | Orpington | 03:30 |

| 463 | Rayleigh & Wickford | 03:30 |

| 468 | Reigate | 03:30 |

| 521 | South Ribble | 03:30 |

| 544 | Streatham | 03:30 |

| 548 | Suffolk Coastal | 03:30 |

| 553 | Surrey Heath | 03:30 |

| 569 | Thirsk & Malton | 03:30 |

| 576 | Torfaen | 03:30 |

| 585 | Ulster Mid | 03:30 |

| 590 | Vauxhall | 03:30 |

| 593 | Walsall North | 03:30 |

| 594 | Walsall South | 03:30 |

| 598 | Warley | 03:30 |

| 607 | Weaver Vale | 03:30 |

| 612 | West Bromwich East | 03:30 |

| 613 | West Bromwich West | 03:30 |

| 614 | West Ham | 03:30 |

| 634 | Worcestershire Mid | 03:30 |

| 640 | Wrekin, The | 03:30 |

| 5 | Aberdeenshire West & Kincardine | 04:00 |

| 7 | Aldershot | 04:00 |

| 19 | Ashfield | 04:00 |

| 23 | Ayr, Carrick & Cumnock | 04:00 |

| 24 | Ayrshire Central | 04:00 |

| 25 | Ayrshire North & Arran | 04:00 |

| 27 | Banff & Buchan | 04:00 |

| 31 | Barrow & Furness | 04:00 |

| 32 | Basildon & Billericay | 04:00 |

| 43 | Bedfordshire North East | 04:00 |

| 55 | Bexleyheath & Crayford | 04:00 |

| 61 | Birmingham Ladywood | 04:00 |

| 67 | Blackburn | 04:00 |

| 88 | Braintree | 04:00 |

| 93 | Brentwood & Ongar | 04:00 |

| 94 | Bridgend | 04:00 |

| 95 | Bridgwater & Somerset West | 04:00 |

| 99 | Bristol East | 04:00 |

| 101 | Bristol South | 04:00 |

| 105 | Bromsgrove | 04:00 |

| 107 | Broxtowe | 04:00 |

| 114 | Caerphilly | 04:00 |

| 120 | Cambridgeshire North East | 04:00 |

| 124 | Cannock Chase | 04:00 |

| 133 | Carshalton & Wallington | 04:00 |

| 135 | Ceredigion | 04:00 |

| 140 | Chelsea & Fulham | 04:00 |

| 144 | Chesterfield | 04:00 |

| 145 | Chichester | 04:00 |

| 168 | Crawley | 04:00 |

| 173 | Cumbernauld, Kilsyth & Kirkintilloch East | 04:00 |

| 177 | Dartford | 04:00 |

| 183 | Derbyshire Dales | 04:00 |

| 190 | Devon North | 04:00 |

| 191 | Devon South West | 04:00 |

| 192 | Devon West & Torridge | 04:00 |

| 194 | Don Valley | 04:00 |

| 195 | Doncaster Central | 04:00 |

| 196 | Doncaster North | 04:00 |

| 200 | Dorset West | 04:00 |

| 204 | Dudley North | 04:00 |

| 205 | Dudley South | 04:00 |

| 207 | Dumfries & Galloway | 04:00 |

| 208 | Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale & Tweeddale | 04:00 |

| 225 | Eastbourne | 04:00 |

| 228 | Edinburgh East | 04:00 |

| 229 | Edinburgh North & Leith | 04:00 |

| 230 | Edinburgh South | 04:00 |

| 231 | Edinburgh South West | 04:00 |

| 232 | Edinburgh West | 04:00 |

| 236 | Eltham | 04:00 |

| 240 | Epsom & Ewell | 04:00 |

| 242 | Erith & Thamesmead | 04:00 |

| 243 | Esher & Walton | 04:00 |

| 246 | Fareham | 04:00 |

| 253 | Folkestone & Hythe | 04:00 |

| 258 | Garston & Halewood | 04:00 |

| 259 | Gateshead | 04:00 |

| 270 | Gloucester | 04:00 |

| 278 | Greenwich & Woolwich | 04:00 |

| 279 | Guildford | 04:00 |

| 280 | Hackney North & Stoke Newington | 04:00 |

| 281 | Hackney South & Shoreditch | 04:00 |

| 286 | Hammersmith | 04:00 |

| 289 | Hampshire North West | 04:00 |

| 291 | Harborough | 04:00 |

| 294 | Harrow East | 04:00 |

| 295 | Harrow West | 04:00 |

| 306 | Hereford & Herefordshire South | 04:00 |

| 311 | Hertsmere | 04:00 |

| 313 | Heywood & Middleton | 04:00 |

| 332 | Ipswich | 04:00 |

| 336 | Islwyn | 04:00 |

| 341 | Kettering | 04:00 |

| 361 | Leigh | 04:00 |

| 362 | Lewes | 04:00 |

| 363 | Lewisham Deptford | 04:00 |

| 364 | Lewisham East | 04:00 |

| 365 | Lewisham West & Penge | 04:00 |

| 380 | Luton North | 04:00 |

| 381 | Luton South | 04:00 |

| 383 | Maidenhead | 04:00 |

| 390 | Mansfield | 04:00 |

| 392 | Meriden | 04:00 |

| 401 | Monmouth | 04:00 |

| 409 | New Forest East | 04:00 |

| 411 | Newark | 04:00 |

| 413 | Newcastle-under-Lyme | 04:00 |

| 414 | Newcastle upon Tyne Central | 04:00 |

| 415 | Newcastle upon Tyne East | 04:00 |

| 416 | Newcastle upon Tyne North | 04:00 |

| 422 | Norfolk North | 04:00 |

| 429 | Northamptonshire South | 04:00 |

| 432 | Nottingham East | 04:00 |

| 433 | Nottingham North | 04:00 |

| 434 | Nottingham South | 04:00 |

| 437 | Ogmore | 04:00 |

| 438 | Old Bexley & Sidcup | 04:00 |

| 441 | Orkney & Shetland | 04:00 |

| 447 | Pendle | 04:00 |

| 448 | Penistone & Stocksbridge | 04:00 |

| 449 | Penrith & The Border | 04:00 |

| 452 | Plymouth Moor View | 04:00 |

| 453 | Plymouth Sutton & Devonport | 04:00 |

| 459 | Preseli Pembrokeshire | 04:00 |

| 467 | Redditch | 04:00 |

| 473 | Richmond Park | 04:00 |

| 476 | Rochford & Southend East | 04:00 |

| 478 | Romsey & Southampton North | 04:00 |

| 485 | Runnymede & Weybridge | 04:00 |

| 489 | Saffron Walden | 04:00 |

| 497 | Scarborough & Whitby | 04:00 |

| 501 | Selby & Ainsty | 04:00 |

| 502 | Sevenoaks | 04:00 |

| 523 | Southampton Itchen | 04:00 |

| 524 | Southampton Test | 04:00 |

| 525 | Southend West | 04:00 |

| 527 | Spelthorne | 04:00 |

| 529 | Staffordshire Moorlands | 04:00 |

| 546 | Stroud | 04:00 |

| 547 | Suffolk Central & Ipswich North | 04:00 |

| 549 | Suffolk South | 04:00 |

| 554 | Surrey South West | 04:00 |

| 555 | Sussex Mid | 04:00 |

| 556 | Sutton & Cheam | 04:00 |

| 557 | Sutton Coldfield | 04:00 |

| 578 | Tottenham | 04:00 |

| 580 | Tunbridge Wells | 04:00 |

| 581 | Twickenham | 04:00 |

| 602 | Warwickshire North | 04:00 |

| 606 | Wealden | 04:00 |

| 616 | Westmorland & Lonsdale | 04:00 |

| 617 | Weston-Super-Mare | 04:00 |

| 618 | Wigan | 04:00 |

| 620 | Wiltshire South West | 04:00 |

| 626 | Witham | 04:00 |

| 628 | Woking | 04:00 |

| 635 | Worcestershire West | 04:00 |

| 644 | Wyre Forest | 04:00 |

| 18 | Arundel & South Downs | 04:30 |

| 26 | Banbury | 04:30 |

| 37 | Batley & Spen | 04:30 |

| 51 | Berwickshire, Roxburgh & Selkirk | 04:30 |

| 54 | Bexhill & Battle | 04:30 |

| 58 | Birmingham Erdington | 04:30 |

| 96 | Brigg & Goole | 04:30 |

| 138 | Cheadle | 04:30 |

| 147 | Chippenham | 04:30 |

| 148 | Chipping Barnet | 04:30 |

| 152 | Clacton | 04:30 |

| 157 | Colchester | 04:30 |

| 158 | Colne Valley | 04:30 |

| 159 | Congleton | 04:30 |

| 161 | Corby | 04:30 |

| 169 | Crewe & Nantwich | 04:30 |

| 178 | Daventry | 04:30 |

| 187 | Devizes | 04:30 |

| 193 | Dewsbury | 04:30 |

| 235 | Elmet & Rothwell | 04:30 |

| 271 | Gordon | 04:30 |

| 275 | Gravesham | 04:30 |

| 297 | Harwich & Essex North | 04:30 |

| 301 | Hazel Grove | 04:30 |

| 309 | Hertfordshire North East | 04:30 |

| 319 | Horsham | 04:30 |

| 322 | Huddersfield | 04:30 |

| 328 | Ilford North | 04:30 |

| 329 | Ilford South | 04:30 |

| 340 | Kensington | 04:30 |

| 349 | Lancashire West | 04:30 |

| 351 | Leeds Central | 04:30 |

| 352 | Leeds East | 04:30 |

| 353 | Leeds North East | 04:30 |

| 354 | Leeds North West | 04:30 |

| 355 | Leeds West | 04:30 |

| 360 | Leicestershire South | 04:30 |

| 394 | Middlesbrough | 04:30 |

| 400 | Mole Valley | 04:30 |

| 405 | Morley & Outwood | 04:30 |

| 420 | Newton Abbot | 04:30 |

| 424 | Norfolk South | 04:30 |

| 430 | Norwich North | 04:30 |

| 431 | Norwich South | 04:30 |

| 461 | Pudsey | 04:30 |

| 466 | Redcar | 04:30 |

| 496 | Salisbury | 04:30 |

| 498 | Scunthorpe | 04:30 |

| 503 | Sheffield Brightside & Hillsborough | 04:30 |

| 504 | Sheffield Central | 04:30 |

| 505 | Sheffield Hallam | 04:30 |

| 506 | Sheffield Heeley | 04:30 |

| 507 | Sheffield South East | 04:30 |

| 510 | Shrewsbury & Atcham | 04:30 |

| 519 | Somerton & Frome | 04:30 |

| 532 | Stevenage | 04:30 |

| 534 | Stockport | 04:30 |

| 577 | Totnes | 04:30 |

| 582 | Tynemouth | 04:30 |

| 583 | Tyneside North | 04:30 |

| 619 | Wiltshire North | 04:30 |

| 627 | Witney | 04:30 |

| 630 | Wolverhampton North East | 04:30 |

| 631 | Wolverhampton South East | 04:30 |

| 632 | Wolverhampton South West | 04:30 |

| 9 | Altrincham & Sale West | 05:00 |

| 20 | Ashford | 05:00 |

| 36 | Bath | 05:00 |

| 39 | Beaconsfield | 05:00 |

| 52 | Bethnal Green & Bow | 05:00 |

| 53 | Beverley & Holderness | 05:00 |

| 56 | Birkenhead | 05:00 |

| 62 | Birmingham Northfield | 05:00 |

| 65 | Birmingham Yardley | 05:00 |

| 79 | Bootle | 05:00 |

| 80 | Boston & Skegness | 05:00 |

| 85 | Bradford East | 05:00 |

| 86 | Bradford South | 05:00 |

| 87 | Bradford West | 05:00 |

| 92 | Brentford & Isleworth | 05:00 |

| 97 | Brighton Kemptown | 05:00 |

| 98 | Brighton Pavilion | 05:00 |

| 110 | Burton | 05:00 |

| 115 | Caithness, Sutherland & Easter Ross | 05:00 |

| 116 | Calder Valley | 05:00 |

| 119 | Cambridge | 05:00 |

| 137 | Chatham & Aylesford | 05:00 |

| 146 | Chingford & Woodford Green | 05:00 |

| 149 | Chorley | 05:00 |

| 165 | Coventry North East | 05:00 |

| 166 | Coventry North West | 05:00 |

| 167 | Coventry South | 05:00 |

| 174 | Cynon Valley | 05:00 |

| 197 | Dorset Mid & Poole North | 05:00 |

| 198 | Dorset North | 05:00 |

| 199 | Dorset South | 05:00 |

| 218 | Ealing Central & Acton | 05:00 |

| 219 | Ealing North | 05:00 |

| 247 | Faversham & Kent Mid | 05:00 |

| 248 | Feltham & Heston | 05:00 |

| 249 | Fermanagh & South Tyrone | 05:00 |

| 252 | Finchley & Golders Green | 05:00 |

| 257 | Gainsborough | 05:00 |

| 274 | Grantham & Stamford | 05:00 |

| 282 | Halesowen & Rowley Regis | 05:00 |

| 284 | Haltemprice & Howden | 05:00 |

| 303 | Hemsworth | 05:00 |

| 304 | Hendon | 05:00 |

| 307 | Herefordshire North | 05:00 |

| 315 | Hitchin & Harpenden | 05:00 |

| 321 | Hove | 05:00 |

| 327 | Hyndburn | 05:00 |

| 331 | Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch & Strathspey | 05:00 |

| 338 | Keighley | 05:00 |

| 366 | Leyton & Wanstead | 05:00 |

| 370 | Liverpool Riverside | 05:00 |

| 371 | Liverpool Walton | 05:00 |

| 372 | Liverpool Wavertree | 05:00 |

| 373 | Liverpool West Derby | 05:00 |

| 378 | Louth & Horncastle | 05:00 |

| 384 | Maidstone & The Weald | 05:00 |

| 391 | Meon Valley | 05:00 |

| 410 | New Forest West | 05:00 |

| 426 | Normanton, Pontefract & Castleford | 05:00 |

| 454 | Pontypridd | 05:00 |

| 455 | Poole | 05:00 |

| 456 | Poplar & Limehouse | 05:00 |

| 470 | Rhondda | 05:00 |

| 472 | Richmond (Yorks) | 05:00 |

| 475 | Rochester & Strood | 05:00 |

| 480 | Rossendale & Darwen | 05:00 |

| 483 | Rugby | 05:00 |

| 488 | Rutland & Melton | 05:00 |

| 490 | St Albans | 05:00 |

| 495 | Salford & Eccles | 05:00 |

| 499 | Sedgefield | 05:00 |

| 500 | Sefton Central | 05:00 |

| 508 | Sherwood | 05:00 |

| 509 | Shipley | 05:00 |

| 512 | Sittingbourne & Sheppey | 05:00 |

| 518 | Somerset North East | 05:00 |

| 526 | Southport | 05:00 |

| 541 | Stourbridge | 05:00 |

| 543 | Stratford-on-Avon | 05:00 |

| 545 | Stretford & Urmston | 05:00 |

| 564 | Taunton Deane | 05:00 |

| 572 | Tiverton & Honiton | 05:00 |

| 575 | Torbay | 05:00 |

| 591 | Wakefield | 05:00 |

| 592 | Wallasey | 05:00 |

| 595 | Walthamstow | 05:00 |

| 599 | Warrington North | 05:00 |

| 600 | Warrington South | 05:00 |

| 622 | Winchester | 05:00 |

| 624 | Wirral South | 05:00 |

| 625 | Wirral West | 05:00 |

| 633 | Worcester | 05:00 |

| 637 | Worsley & Eccles South | 05:00 |

| 648 | York Central | 05:00 |

| 649 | York Outer | 05:00 |

| 650 | Yorkshire East | 05:00 |

| 22 | Aylesbury | 05:30 |

| 34 | Basingstoke | 05:30 |

| 57 | Birmingham Edgbaston | 05:30 |

| 60 | Birmingham Hodge Hill | 05:30 |

| 103 | Broadland | 05:30 |

| 108 | Buckingham | 05:30 |

| 123 | Cambridgeshire South East | 05:30 |

| 188 | Devon Central | 05:30 |

| 277 | Great Yarmouth | 05:30 |

| 283 | Halifax | 05:30 |

| 520 | South Holland & The Deepings | 05:30 |

| 605 | Waveney | 05:30 |

| 3 | Aberdeen North | 06:00 |

| 4 | Aberdeen South | 06:00 |

| 63 | Birmingham Perry Barr | 06:00 |

| 64 | Birmingham Selly Oak | 06:00 |

| 74 | Bognor Regis & Littlehampton | 06:00 |

| 126 | Cardiff Central | 06:00 |

| 127 | Cardiff North | 06:00 |

| 128 | Cardiff South & Penarth | 06:00 |

| 129 | Cardiff West | 06:00 |

| 220 | Ealing Southall | 06:00 |

| 254 | Forest of Dean | 06:00 |

| 261 | Gillingham & Rainham | 06:00 |

| 288 | Hampshire North East | 06:00 |

| 300 | Hayes & Harlington | 06:00 |

| 305 | Henley | 06:00 |

| 350 | Lancaster & Fleetwood | 06:00 |

| 404 | Morecambe & Lunesdale | 06:00 |

| 423 | Norfolk North West | 06:00 |

| 425 | Norfolk South West | 06:00 |

| 444 | Oxford West & Abingdon | 06:00 |

| 464 | Reading East | 06:00 |

| 465 | Reading West | 06:00 |

| 477 | Romford | 06:00 |

| 484 | Ruislip, Northwood & Pinner | 06:00 |

| 492 | St Helens North | 06:00 |

| 493 | St Helens South & Whiston | 06:00 |

| 511 | Shropshire North | 06:00 |

| 537 | Stoke-on-Trent Central | 06:00 |

| 538 | Stoke-on-Trent North | 06:00 |

| 539 | Stoke-on-Trent South | 06:00 |

| 563 | Tatton | 06:00 |

| 566 | Tewkesbury | 06:00 |

| 567 | Thanet North | 06:00 |

| 568 | Thanet South | 06:00 |

| 573 | Tonbridge & Malling | 06:00 |

| 587 | Uxbridge & Ruislip South | 06:00 |

| 597 | Wantage | 06:00 |

| 604 | Watford | 06:00 |

| 629 | Wokingham | 06:00 |

| 638 | Worthing East & Shoreham | 06:00 |

| 639 | Worthing West | 06:00 |

| 21 | Ashton Under Lyne | 06:30 |

| 59 | Birmingham Hall Green | 06:30 |

| 118 | Camborne & Redruth | 06:30 |

| 162 | Cornwall North | 06:30 |

| 163 | Cornwall South East | 06:30 |

| 180 | Denton & Reddish | 06:30 |

| 457 | Portsmouth North | 06:30 |

| 458 | Portsmouth South | 06:30 |

| 491 | St Austell & Newquay | 06:30 |

| 531 | Stalybridge & Hyde | 06:30 |

| 579 | Truro & Falmouth | 06:30 |

| 68 | Blackley & Broughton | 07:00 |

| 317 | Hornchurch & Upminster | 07:00 |

| 356 | Leicester East | 07:00 |

| 357 | Leicester South | 07:00 |

| 358 | Leicester West | 07:00 |

| 382 | Macclesfield | 07:00 |

| 387 | Manchester Central | 07:00 |

| 388 | Manchester Gorton | 07:00 |

| 389 | Manchester Withington | 07:00 |

| 397 | Milton Keynes North | 07:00 |

| 398 | Milton Keynes South | 07:00 |

| 439 | Oldham East & Saddleworth | 07:00 |

| 440 | Oldham West & Royton | 07:00 |

| 479 | Ross, Skye & Lochaber | 07:00 |

| 609 | Wells | 07:00 |

| 645 | Wythenshawe & Sale East | 07:00 |

| 50 | Berwick-upon-Tweed | 12:00 |

| 73 | Blyth Valley | 12:00 |

| 312 | Hexham | 12:00 |

| 339 | Kenilworth & Southam | 12:00 |

| 596 | Wansbeck | 12:00 |

| 601 | Warwick & Leamington | 12:00 |

| 494 | St Ives | 13:00 |

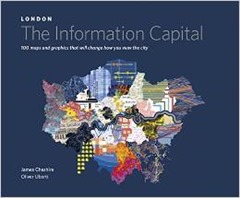

The Information Capital

The Information Capital