Terry Pratchett was recently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and has made a programme, Choosing to die, about his enquiries into assisted suicide. It’s pretty difficult viewing: Pratchett visits the widow of a Belgian writer who, like him, had Alzheimer’s disease and had chosen to end his life. He visits a former taxidriver in a hospice with motor neuron disease, who had chosen not to die. The bulk of the programme is spent with two men who went to the Dignitas clinic in Switzerland, where they were helped to die. Andrew, only a couple of years older than me, with multiple sclerosis and Peter, born in 1939, with motor neuron disease. The death of Peter is shown in full. It’s not this that is my abiding memory though, that will be of the courage and dignity of the wife and mother of these two dying men. Neither woman wants their loved one to go.

The striking thing for me was how both men appeared to be heading off to Switzerland before their time, for fear of not being able to go when they felt they had to. The current legislation seems to be wilfully sadistic, obliging early death for those that chose whilst holding out the threat of prosecution to the family.

The Swiss are allowed to be helped to die at home, whilst foreigners go to die in a small blue apartment in an industrial estate. Incongruously the shallow steps to the front door are protected by black and yellow safety tape: because if you’re going to die you don’t want to fall over and crack your head open. This seems a great pity since in the background you could see the snow clad Swiss Alps, a glorious place to die.

A number of members of my close family have died over the last ten years. I don’t think we’re an unusual family, we’ve discussed assisted dying, often in the aftermath of a death. My paternal grandparents both died in their nineties in retirement homes, very much reduced from their previous vigorous selves, moving gradually to death. My maternal grandparents both died at home, quite suddenly. My stepfather died at home in a hospital bed, cared for by my mum with the support of nurses. He’d known he was going to die since cancer stopped him eating a couple of months earlier. Mum is the bravest person I know.

The consensus in the family appears to be for assisted dying but I think we all know privately that as the law stands now it will not happen. We will be left to face what lingering or sudden deaths nature serves up to us, in the knowledge that modern medicine has got so much better at keeping us alive but not necessarily living.

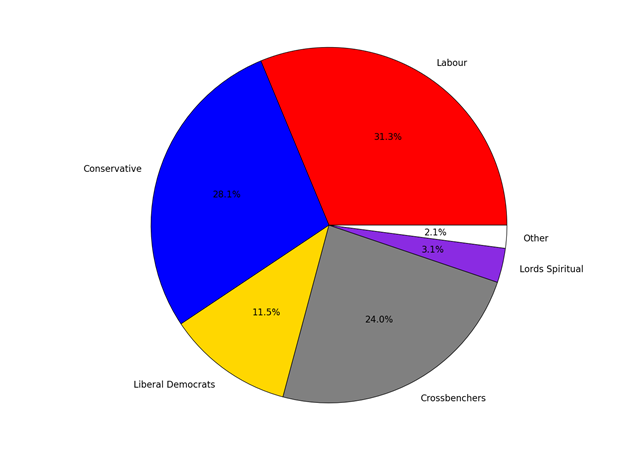

This is one of the few places where my atheism collides with the established church: any time the right to die is discussed it appears to be a Christian or one of the Lords Spiritual who is called upon to make the case against: often citing the idea that my life is a gift from God, and that I have no right to dispose of it. Clearly for an atheist this is an argument discarded in a moment.

I may die in an accident tomorrow. I may hang on to the absolute end waiting to see what is over the the next ridge. Or maybe, when I am old and have had enough, I’ll want to go at a time and place of my choosing.

How I choose to die is none of your business – I won’t presume to choose for you.