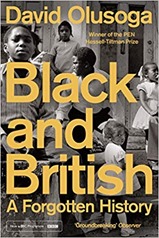

Since October was Black History Month I thought Black and British: A Forgotten History by David Olusoga would make a very appropriate read. Although, to be honest, I bought it before I realised and in all likelihood by the time you read this Black History Month will have finished.

Since October was Black History Month I thought Black and British: A Forgotten History by David Olusoga would make a very appropriate read. Although, to be honest, I bought it before I realised and in all likelihood by the time you read this Black History Month will have finished.

The first thing that struck me about this book was the Preface where Olusoga writes about his motivation for writing the book. As a British-Nigerian this is visceral, the talk by Enoch Powell of “sending back” non-white citizens of Britain meant he feared he would be separated from his family as a boy. When the National Front were hounding people out of their homes, it was he who was being hounded out. This is absolutely in no way a criticism of Olusoga, or a reason to ignore the contents of this book. It is to contrast with my own detached, academic position as a white British reader.

Following an introduction which gives an outline of the contents of the whole book, the chapters proceed in chronological order with some themes relating to the same time covered in separate chapters. I’ve listed these out at the end of this review as a reminder to myself as much as anything.

There have been black people in Britain for thousands of years, the very first were identified during the Roman occupation. The ancient Romans and Greeks knew of Africa and sub-Saharan Africa, and the nature of the Roman Empire was that its subjects were mobile to a degree. After the fall of the Roman Empire, access to Africa was via the Arab/Muslim empire across North Africa with little contact with Europe. As a consequence European knowledge of African was limited to myths. The story picks up again in the 15th century with the Portuguese exploring the West African coast, they also started the slave trade in black Africans. The British took the first tentative steps in the “triangular slave trade” in the 16th century. The triangle trade saw the movement of manufactured goods from Britain to Africa, slaves from Africa to American and raw materials, sugar, tobacco, and cotton back to Britain.

At this time the West African states were powerful, and experienced in trade with the Portuguese and before them the Arabs. European explorers and merchants suffered large loses to disease – a situation which persisted into the 19th century. Black Africans were found as translators, and sailors, even courtiers in Britain. In Lisbon they made up as much as 20% of the population in the 16th century. They were the subject of curiosity, apparently little specific malice due to their colour, but lived under the Christian view that whiteness represented purity, and blackness the opposite.

British involvement in the slave trade picked up as it acquired colonies in the West Indies and US, the production of sugar and tobacco was lucrative if you had a good supply of cheap (slave) labour. It is at this point that black African slaves are dehumanised, the 1661 Barbados Slave Code puts this in writing. Plantation owners in the West Indies cannot see black Africans as human, they are too numerous and too economically valuable to be seen as such. The Royal African Company is formed as an exclusive vehicle for the slave trade in Britain, and is to take up to 75% of the slave trade in the late 17th century and early 18th century.

In Britain the situation is a bit different, there are a growing number of black people, often brought as the property of wealthy slavers, traders and plantation owners. But their legal status in Britain is hazy, and kept deliberately so for much of the 18th century. In the second half of the 18th century Granville Sharp started a campaign to release slaves in Britain, and later to campaign against slavery itself. There was a degree of romanticism in the view that British air was too pure for a slave to breathe, so that none were slaves whilst at the same time profiting massively from slavery. From this start the Abolitionist movement grew, first ending British involvement in the slave trade (with Wilberforces 1807 bill), ending slavery in the West Indies in 1838 and then going on to try to end slavery globally.

This was seen as a moral crusade by the British, although there was a lively circuit of African-American speakers promoting the cause in Britain. Olusoga points out that the British have always been much more willing to talk about Abolition than slavery. In this context black Africans are still not seen as equal people, at least by some Abolitionists, but rather they wish to end slavery in the same way as they wish to see the end of cruelty to animals and children.

Freetown in Sierra Leone became an important location in the story, former slaves played a part fighting on the side of the British in the American Revolution, and their payment was freedom. Britain was squeamish about giving them their freedom in Britain. Some went to Nova Scotia, but there was also a plan to establish Freetown in Sierra Leone. The first attempt at this failed abysmally but eventually a colony was established there and the traces of that early history still remain in the modern city.

The British public appeared fairly well disposed towards black people in the first half of the 19th century but in the second half of the century there was a rise in Social Darwinism and scientific racism. Black people were increasingly spoken off as being mentally inferior, often child-like. These ideas grew from Darwin’s theory of evolution but they were motivated by a desire for conquest. In the final 30 years of the 19th century the white European powers colonised 90% of Africa in the “Scramble for Africa”. A theme that was to recur through the 20th century was an aversion to inter-racial relationships, specifically children fathered by black men with white women.

Britain’s attitude to black men for the two world wars was ambivalent, in both cases they were desperate for soldiers but, particularly in the First World War, very keen that black men should not fight white men – worrying this would give them unhelpful ideas when they returned to their homes in the minority white run colonies. In the Second World War the key feature was the huge influx of African American GIs to Britain, and the greatest issue was the treatment of Africa American GIs by their white colleagues (it was atrocious). British civilians were appalled by this. However in the aftermath of both wars there were racially motivated attacks on black men by organised white mobs. The motivation for this, at least in part, was that demobilised white men felt that black men had jobs that were rightfully theirs and economic times were hard. The official response to this was unhelpful to say the least, largely treating the black men as the transgressors. This treatment echoes down the years, and was part of the mis-trust of the police that fuelled the riots of the early eighties and, if we are honest, is still current today.

The book finishes with the post-war period, looking at the passengers on the Empire Windrush and the rise of Enoch Powell. The cry started by Powell in the seventies was to “send them back”, and picked up by the National Front. Powell was a culmination of a tacit program by governments of both stripes to justify the exclusion of black immigrants which had been ongoing since the Second World War. It was during the sixties that the public started to think the same way in larger numbers.

For West Indians and Africans from a number of modern states, Britain is the “home country”, in the same way as it is for white Canadians, New Zealanders and Australians. The difference is that immigrants from these countries are broadly officially welcomed and have been since the end of the British Empire. Black people have not been given that welcome.

Black and British is quite a long read, it packs a lot in but it is well-structured and readable. For me, as a white British middle class man, Olusoga presents from quite a different viewpoint. This is sometimes uncomfortable but I think necessarily so. It helps make more sense of the recent Black Lives Matter movement, but also the racism of the 1970s and the riots of the early eighties, in Britain, with smaller recurrences more recently.

Chapter Themes

- Sons of Ham – black people in Roman Britain and onwards, the start of the British slave trade in the 16th century;

- Blackamoors – black people in Tudor Britain, the development of the slave trade through to the end of the 18th century to service the tobacco and sugar plantations in the West Indies and America;

- For Blacks or Dogs – black people in Georgian Britain, the overspill of the slave trade;

- Too Pure an Air for Slaves – Granville Sharp and the start of the Abolitionist movement in the late 18th Century;

- Province of Freedom – Africa Americans and the American Revolution, leading to the foundation of Freetown in Sierra Leone;

- The Monster is Dead – the path to Abolition with the trade banned in 1806 and slavery in the West Indies banned in 1838;

- Moral Mission – British mission to end slavery around the world in the Victorian period, with black speakers touring Britain. Minstrelism;

- Liberated Africans – the West Africa Squadron, aiming to abolish slavery by military means, the conquest of Lagos;

- Cotton is King – the US civil war and its impact on the cotton mills of northern England;

- Mercy in a Massacre – the rise of Social Darwinism and scientific racism in the second half of the 19th century;

- Darkest Africa – the 30 year Scrabble for Africa, when the Europeans colonised all but Ethiopia and Liberia. The rise of human zoos;

- We are a Coloured Empire – World War I and the black British Empire;

- We Prefer their Company – World War II and African American GIs;

- Swamped – immigration to post-war Britain;