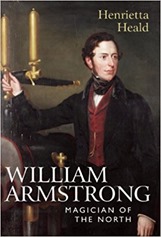

A return to industrial history with  William Armstrong: Magician of the North by Henrietta Armstrong. Armstrong was a 19th century industrialist who spent his life in the north-east of England around Newcastle. His great industrial innovation was the introduction of hydraulic power to cranes and the like. His great wealth, and honours (a knighthood and then a baronetcy) derived from his work in the invention and sale of armaments principally artillery and ships. His home, Cragside near Rothbury some 30 miles north of Newcastle upon Tyne, was the first to feature electric lighting amongst many other technical innovations.

William Armstrong: Magician of the North by Henrietta Armstrong. Armstrong was a 19th century industrialist who spent his life in the north-east of England around Newcastle. His great industrial innovation was the introduction of hydraulic power to cranes and the like. His great wealth, and honours (a knighthood and then a baronetcy) derived from his work in the invention and sale of armaments principally artillery and ships. His home, Cragside near Rothbury some 30 miles north of Newcastle upon Tyne, was the first to feature electric lighting amongst many other technical innovations.

Armstrong was a contemporary of Robert Stephenson, Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Joseph Whitworth – they were all born near the beginning of the 19th century, Armstrong dying in 1900 outlasted them all with Brunel and Robert Stephenson dying in 1859.

Armstrong was born in 1910 his parents started him on a career in the law. However, he had always been fascinated by water. This led to his realisation that the power that could be extracted from a head of water in a sealed system. A water wheel extracts energy from water falling the height of the wheel, a matter of a few metres. A sealed iron pipe, such as could now be manufactured allowed you to capture the energy from a fall of tens of metres or more. In Newcastle upon Tyne the local landscape could provide this head of pressure but with a little ingenuity the head of pressure could be created with a steam engine or other mechanical means. This energy could be used to drive all manner of machinery, Armstrong initially used it to power cranes, and lock gates, to be used in docks and the many factories springing up around the country. Ultimately his hydraulic mechanisms drove London’s Tower Bridge.

In the aftermath of the Crimean War, Armstrong switched his attention to building artillery. During the Crimean War the British artillery was found wanting in terms of accuracy, destructive power and firing rate. His innovations were to move from cannonballs to shells (shaped like bullets), and from muzzle loading to breech loading. He gave up the patents for his artillery pieces to the government but made a fair business on them. His activities with ordnance led to his knighthood and baronetcy although ultimately he withdraw from the close relationship with the British government in armaments as a result of political manoeuvrings by competitors.

The manufacture of artillery led to the manufacture of warships, which incidentally also carried the artillery. The Japanese Navy were particularly important.

He was a leading light of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne (Lit & Phil), and contributed to founding what is now Newcastle University. Late in his life, in 1897, he published Electric movement in air and water based on his experiments and featuring cutting-edge photographs of the phenomena he described. From a scientific point of view, Armstrong is not a name you will hear in physics classrooms (at any level) today – I don’t know if the same holds for his engineering innovations. Also late in his life he bought Bamburgh Castle, and spent a fair amount of money refurbishing it.

Magician of the North is a somewhat sympathetic view of Armstrong, along the lines of Man of Iron by Julian Glover about Thomas Telford. This contrasts with Samuel Smiles biography of George Stephenson and Rolt’s of Brunel which are much more effusive about their subjects. The Armstrong’s arms trading is discussed in some detail, it seems the company sailed somewhat close to the wind legally in supplying both sides in the American Civil War. A second blemish on Armstrong’s reputation came from industrial disputes with his, and other workers on the Tyne, asking for shorting working hours. That said, he was clearly a pillar of the Newcastle and north eastern community and highly regarded by most of the people most of the time. Many buildings in Newcastle bore his name as a result of his donations both whilst he was a live and after he died.

As usual the author of this biography bemoans the limited attention their subject has received. In the case of Armstrong they put this down to his extensive involvement in the arms trade which, never the most popular, was to fall further out of favour following the Great War. I’ve never seen a quantitative analysis of what makes the right amount of attention for figures in the history of science and technology.

William Armstrong died in 1900, after his death his company went into a slow decline. The Great War led to a distaste for the arms trade, and then came the Great Depression. With Armstrong gone there was no strong, capable leader for the company. The Armstrong name lived on in various spin off companies such as Armstrong Siddeley and various amalgamations with Whitworths and Vickers.

Leviathan and the air-pump

Leviathan and the air-pump