This post was first published at ScraperWiki.

This week I’ve been programming in JavaScript, something of a novelty for me. Jealous of the Dear Leader’s automatically summarize tool I wanted to make something myself, hopefully a future post will describe my timeline visualising tool. Further motivations are that web scraping requires some knowledge of JavaScript since it is a key browser technology and, in its prototypical state, the ScraperWiki platform sometimes requires you to launch a console and type in JavaScript to do stuff.

I have two books on JavaScript, the one I review here is JavaScript: The Good Parts by Douglas Crockford – a slim volume which tersely describes what the author feels the best bits of JavaScript, incidently highlighting the bad bits. The second book is the JavaScript Bible by Danny Goodman, Michael Morrison, Paul Novitski, Tia Gustaff Rayl which I bought some time ago, impressed by its sheer bulk but which I am unlikely ever to read let alone review!

Learning new programming languages is easy in some senses: it’s generally straightforward to get something to happen simply because core syntax is common across many languages. The only seriously different language I’ve used is Haskell. The difficulty with programming languages is idiom, the parallel is with human languages: the barrier to making yourself understood in a language is low, but to speak fluently and elegantly needs a higher level of understanding which isn’t simply captured in grammar. Programming languages are by their nature flexible so it’s quite possible to write one in the style of another – whether you should do this is another question.

My first programming language was BASIC, I suspect I speak all other computer languages with a distinct BASIC accent. As an aside, Edsger Dijkstra has said:

[…] the teaching of BASIC should be rated as a criminal offence: it mutilates the mind beyond recovery.

– so perhaps there is no hope for me.

JavaScript has always felt to me a toy language: it originates in a web browser and relies on HTML to import libraries but nowadays it is available on servers in the form of node.js, has a wide range of mature libraries and is very widely used. So perhaps my prejudices are wrong.

The central idea of JavaScript: The Good Parts is to present an ideal subset of the language, the Good Parts, and ignore the less good parts. The particular bad parts of which I was glad to be warned:

- JavaScript arrays aren’t proper arrays with array-like performance, they are weird dictionaries;

- variables have function not block scope;

- unless declared inside a function variables have global scope;

- there is a difference between the equality == and === (and similarly the inequality operators). The short one coerces and then compares, the longer one does not, and is thus preferred.

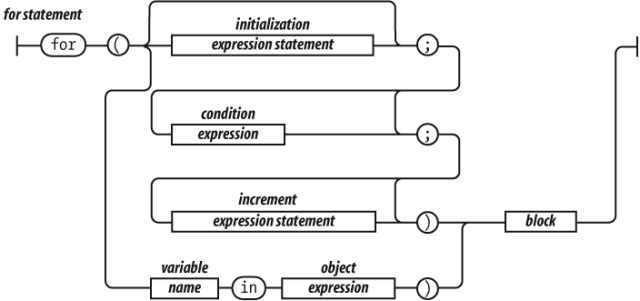

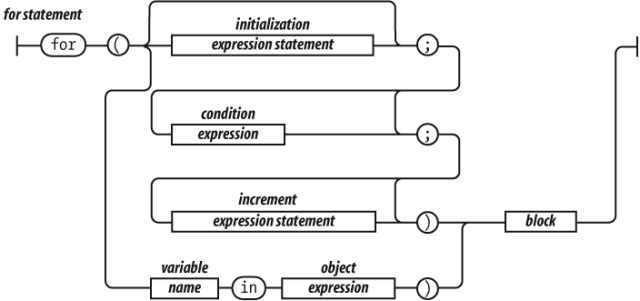

I liked the railroad presentation of syntax and the section on regular expressions is good too.

Elsewhere Crockford has spoken approvingly of CoffeeScript which compiles to JavaScript but is arguably syntactically nicer, it appears to hide some of the bad parts of JavaScript which Crockford identifies.

If you are new to JavaScript but not to programming then this is a good book which will give you a fine start and warn you of some pitfalls. You should be aware that you are reading about Crockford’s ideal not the code you will find in the wild.