And so after 10 days, I finally had a chance to play with my new telescope on Friday night! Optical astronomy requires at least a few gaps in the clouds but last night at 8pm it was completely clear – I was hopping up and down like an overactive child waiting for the sun to go down (scheduled for about 8:40pm) and simultaneously cursing the slightest wisp of cloud. It should be clear that I’m a bit new to this, so what I write shouldn’t be seen as in the slightest bit authorative.

Kindly folk at @newburyastro had suggested Venus and Saturn as targets for my first adventure into the night. Useful advice because, as a relative beginner I had little idea what I was going to see, or in fact when I was going to see it. Venus become visible at about 9:20pm towards the now-set sun, it turns out that pointing the ‘scope with the finderscope is much easier than the rather more hazardous enterprise of finding the sun without (something I describe here). In the eyepiece Venus appears as a small, bright crescent.

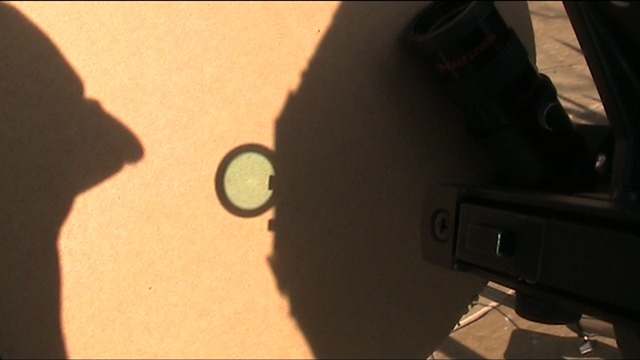

It was a breezy evening which meant that my view jiggled about a bit, it also jiggled about a bit whenever I touched the telescope. However I did manage a picture of Venus taken on my Canon 400D at prime focus. This is an uncropped view, and it’s upside down.

Mars made an appearance a little later at about 9:35pm along with a bright star which I believe is Regulus. This enabled me to get my telescope to work out how it was orientated meaning it could track to objects on demand and also tell me what I was looking at (very handy for a novice). My picture of Mars is a little uninspiring, I’ve zoomed in here as far as possible, in Mars’ favour it does look red and it isn’t a simple point.

By now more and more stars were coming out, so I thought I’d try out my piggyback mount. This image is taken with a 10mm lens (i.e. really wide angle) with the telescope simply used as a camera mount pointed at Polaris, it’s a 30s exposure.

It took a while to get this because I had auto-focus on and the camera couldn’t find anything to focus on so wouldn’t fire – switching off auto-focus and focusing to infinity manually resolved this. It was at this point I wished I could remember how to switch the display on the back of my camera off because it was really bright, and remember which button was which without being able to see it. The thing that surprised me about this is that there are rather more stars than I could see with my naked eye and some of them are quite strongly coloured. I feel I should go about identifying the stars in my picture.

At this point I thought I’d give Saturn a go, I must admit I thought it was hidden behind buildings and trees from my position in the back garden but I punched it into the telescope handset and it pointed me into the side of the conservatory, so I picked up the telescope and moved it one metre to the right, peered through the finderscope and tweaked my direction a bit and… the planet with ears popped into view!! This was really exciting! I only have one eyepiece for my telescope and it’s quite low magnification but through the eyepiece I could see my target was not a point, and it was not round – it was shaped like a flying saucer and there were slight gaps either side of the central body. Having marvelled at this for a bit I thought I’d try for another photograph:

It’s not the best picture of Saturn taken last night but it is my picture!

The moon hadn’t risen before I went to bed, so when I spotted this morning I rushed out for a photo.

I’ve not done any astrophotography before these (apart from my shots of the sun, and a couple of shots at the moon through a conventional lens). I guess the thing I carried over from that was that the moon is a rock in full sun, so you need to set your exposure times accordingly, the same is true for Mars and Venus so I suspect I should be using shorter exposure times for them to which will also reduce any motion blur.

My first night of viewing has highlighted a need to have a better grip of how to work your camera, plan what you want to look at in advance and, as with an SLR camera, a telescope is simply a gateway drug for further accessory purchase.