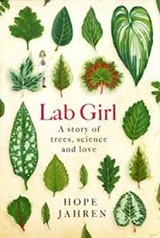

Lab Girl by Hope Jahren is an unusual book. It’s an autobiography which mixes in a fair amount of plant science. It is beautiful to read. It is strong on what being a scientist means. The closest comparison I can think of are Richard Feymann’s “Surely you are joking, Mr Feynmann” memoirs which are rather more anecdotal.

Lab Girl by Hope Jahren is an unusual book. It’s an autobiography which mixes in a fair amount of plant science. It is beautiful to read. It is strong on what being a scientist means. The closest comparison I can think of are Richard Feymann’s “Surely you are joking, Mr Feynmann” memoirs which are rather more anecdotal.

Lab Girl is chronological, starting from Jahren’s early memories of visiting the lab in her father’s school after hours but then fast forwarding to her academic career setting up laboratories in Georgia, Baltimore and finally Hawaii. It isn’t encyclopaedic in providing a detailed record of Jahren’s personal and scientific life.

A thread through the whole book is Bill, her trusty research assistant. Bill starts as a keen undergraduate who Jahren takes on when she gets her first academic position. I think in some ways Bill is something of a product of the US academic system, with support staff often funded on short term grants. In the UK such people tend to be employed on a permanent basis by the institution. My Bill was Tom when I was a PhD student, Pete and Roger when I was an assistant director of research. As a lecturer I didn’t have a Bill, and maybe that was my problem.

Several themes intertwine through the book. There is the day to day activity of a lab: labelling things, repetitive sample preparation, measuring things, fighting with equipment to get it to measure things. Wrangling undergraduates and postgraduates. There are trips out into the field. For Jahren, as a biologist, the field is very literally the field (or Irish bog, Canadian tundra etc). There is attending academic conferences. Mixed with this there is the continual struggle for tenure and funding for your research and the fight for resources with grants that don’t go quite far enough.

It’s fair to say Jahren put in an awful lot more hours than I did as a young academic but then I didn’t turn into an successful, older academic. Make of that what you will. It’s difficult to measure your success as an academic, grant applications are so hit and miss that winning them is only a measure of your luck and skill at writing grant applications, papers are relatively sparse and rarely provide much feedback. Sometimes putting in hours seems the only way of measuring your worth.

A second strand is plant biology, mingling basic background and the cutting edge research that Jahren does. I absorbed this in ambient fashion, I now think a little more like a tree. I didn’t realise that willow deliberately drop whole branches so as to propagate themselves. This explains the success of our willow dome construction which was made by unceremoniously plonking willow sticks into the ground and weaving them together. They then gamely got on and grew. Soil is a recurring theme in the book, the teaching of the taxonomy of soil to undergraduates in particular. I had glimpses of this rich topic whilst doing a Kaggle challenge on tree cover. Finally, there is mass spectroscopy and isotope analysis.

And finally there is the personal, Jahren’s mental health, her struggles with pregnancy, marriage and a growing son. Some of this is painful and personal reading but its good to hear someone saying what we perhaps find unsayable. Lab Girl says relatively little about the difficulties she particularly faced as a woman, although Jahren has written about it elsewhere.

I observed a while back when reviewing In Defence of History that whilst historians seemed interested in literary style in technical writing, scientists rarely did. Lab Girl is an exception, which makes it well worth a read.

At the end of the book, Jahren asks us all to plant a tree. I pleased to say we’ve achieved this, although perhaps not quite the right sort of trees for American sensibilities, used to larger gardens. In the front garden we have a crab apple tree which, in the right sort of year, flowers on my birthday. There are several apple trees spread through the front garden. In both front and back gardens we have acers and now, at the bottom of the garden we have an amelanchier. I have longed for a Cedar of Lebanon in my front garden but fear I will never own a house large enough for this to be practicable.