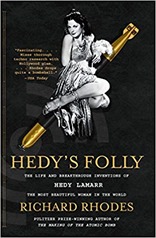

Back to some history of technology with  Hedy’s Folly by Richard Rhodes. This book concerns the patent granted to Hedy Lamarr, Hollywood actress, and George Antheil, experimental musician, for the frequency hopping radio communications system. Originally it was intended to allow secure, jamming resistant communications between torpedoes and their control aircraft or ships, nowadays it is most notably the basis for Bluetooth and WiFi communications.

Hedy’s Folly by Richard Rhodes. This book concerns the patent granted to Hedy Lamarr, Hollywood actress, and George Antheil, experimental musician, for the frequency hopping radio communications system. Originally it was intended to allow secure, jamming resistant communications between torpedoes and their control aircraft or ships, nowadays it is most notably the basis for Bluetooth and WiFi communications.

I’ve previously read Richard Rhodes “The Making of the Atomic Bomb”, which is a massive tome, Hedy’s Folly is a rather more modest affair. It provides some biographical material on Lamarr (born Hedwig Kiesler) and Antheil but only in as much as it leads to the patent of the title.

Hedy Lamarr was born in Austria in 1914, to a wealthy family – her father was banker who clearly cultivated her interest in how things worked. Following a brief career in European theatre and film she married Fritz Mandl in 1933. He was an arms manufacturer and one of the richest men in Austria. He didn’t want to see his wife continue her acting career. On the death of her father Lamarr resolved to leave her husband but in the interim she paid close attention to the technical discussions on armaments which she was party to. In all likelihood she was doing this throughout her marriage, despite his controlling nature Mandl clearly valued her opinions (even if he didn’t like them). Lamarr then moved to the States with Louis Mayer of MGM for whom was to make a number of films. In this milieu she met George Antheil.

Antheil in Trenton, New Jersey in 1900. He travelled to Europe in 1921 where he composed the Ballet Mécanique, originally intended as the score to a film it ended up twice the length of the film. As originally envisaged Ballet Mécanique required 16 player pianos and an aeroplane propeller – amongst many other sound making devices. Essentially Antheil vision was much in advance of what technology in the twenties and thirties could deliver. The player piano plays a part in the story. Player pianos were briefly popular as a way for everyone (who could afford one) to make music, they were automated pianos programmed using a paper roll with holes directing the music. The operator simply had to provide power and rhythm. They were supplanted by radio. The important feature was the ability to control sound automatically.

Antheil returned to the US, to Hollywood, in 1936 where he turned to writing film scores, his experimental music proving rather unpopular. It was here he met Hedy Lamarr.

The spirit of the Second World War in the US was that everyone would do what they could to help. Antheil had a sideline in writing about endocrinology, and made suggests on how to defeat the Nazis by this approach. Later in the war Hedy Lamarr was to do considerable work in encouraging Americans to buy government bonds to support the war effort, as well as volunteering at the Hollywood Canteen – entertainment for servicemen.

Lamarr was an inventor in her spare time, her background meant she knew the problems faced with torpedo guidance. So it was not unsurprising for her to work with Antheil on a frequency hopping patent for torpedo guidance. The central idea of the frequency hopping patent was to transmit radio instructions between controller and torpedo over a series of radio channels at different frequencies switching synchronously between channels. In the original patent the number of channels used is relatively small (less than 10), hops are relatively slow – of order minutes and were controlled by a player piano style roll.

The US Navy chose not to develop the patent, stating that the apparatus was too bulky. This seems to be a bit of a misunderstanding – the player piano inspiration was indeed quite bulky but could easily reduced in size using current technology. More likely was the fact that US torpedo performance at the beginning of the war was abysmal – 60% of torpedos experienced technical failure, so it was likely they had other priorities.

Lamarr and Antheil’s patent on frequency hopping expired in 1959, the US military implemented several frequency hopping systems from the beginning of the sixties. As technology improved it evolved to so-called spread spectrum techniques. The difference between frequency hopping and spread spectrum is really just one of scale. These techniques finally became public in 1976.

Spread spectrum techniques eventually found important applications in Bluetooth and WiFi. Originally designed to be resistant to jamming – the deliberate use of noise to block signals – it is also resistant to unintentional noise. Furthermore it can be used with very low power transmissions so it can cohabit with other signals used for longer range applications and parts of the electromagnetic spectrum where there is a lot of noise.

Hedy Lamarr’s part in the development of frequency hopping is finally being recognised, and George Antheil’s more experimental music is finally being recognised too – technology has now reached the point where his original vision can finally be realised.

This is a fascinating little book, focused on one small invention with huge consequences. It isn’t a biography of Hedy Lamarr, and it isn’t a biography of her co-inventor George Antheil.