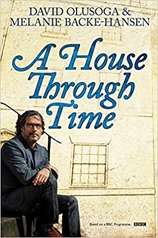

I’ve recently enjoyed watching A house through time, a series presented by David Olusoga tracking the history of a single house and its inhabitants across the years. The most recent series looked at house in Bristol, the city where I was an undergraduate. A house through time by David Olusoga and Melanie Backe-Hansen is the book of the series.

I’ve recently enjoyed watching A house through time, a series presented by David Olusoga tracking the history of a single house and its inhabitants across the years. The most recent series looked at house in Bristol, the city where I was an undergraduate. A house through time by David Olusoga and Melanie Backe-Hansen is the book of the series.

Rather than focus on a single house, as the TV series does, the book is a much broader sweep which looks at the history of the domestic dwelling back to Roman times, research methods and some social history which gives the “why” behind the houses.

This is a busman’s holiday for me, a large chunk of my job over the last few years has been to build a property database to help answer buildings insurance application questions. One of these questions is the property age, and it has been the cause of greatest pain for me. A house is a good background to this type of work, it provides the type of context which can be really helpful in understanding the data I come across. The issue for me though is that A house is written for those wishing to understand their own homes, rather than work out property age for 25 million or so dwellings but this is a niche interest and shouldn’t be taken as a criticism.

The book starts with a chapter on methods: how do you find out about your house? This is supported by an extensive set of links and a bibliography which strikes the happy medium between not providing any references, and referencing alternate words. The Census, and various surveys conducted before and during World War II are core to this, although these are ostensibly about people they provide evidence that an address existed at a point in time give or take variability in addresses and levels of details in addresses. Numbering of houses, as opposed to names, only started to rise in the middle of the 18th century. Also relevant are Ordnance Survey’s historical maps.

I was a bit surprised that there was very little mention of the listed building data, English Heritage and its partner organisations in Wales and Scotland aim to list all building built in the Georgian period and before. The data provides descriptions of the listed structures, this is the entry for 10 Guinea Street, Bristol which featured in one of the TV programmes.

There then follows a set of chapters on different periods, working forward in time covering the pre-Georgian, Georgian, Victorian, Interwar and post-war periods. These are the divisions I use in my work with the insurance industry (with the addition of a modern period starting in 1980).

There are a number of themes threaded through the book, much of the technological development of home building was relatively early. After the Roman’s left Britons reverted to living in wattle-and-daub or timber buildings for 400 years. The next significant technological developments were the discovery, and widening use of the chimney in the late 14th century followed by the re-discovery of brick making in the later 15th century. After that the next clear developments in building were in prefabricated and high-rise buildings post-Second World War.

A second theme is the legislative framework in which buildings wear built, these are two-fold there are “public safety” acts which are used to try to ensure safer buildings are built, these include the laws put in place after the Great Fire and those used to address the unsanitary conditions in Victorian slums in the later 19th century. These acts often specified a limited number of “model” properties and wonder whether these can be used for dating. There were also acts relating to taxation: window and brick taxes. It is the brick taxes that led to the standardisation of bricks, originally bricks were taxed by number so people made larger bricks so as to reduce their tax bills!

It is perhaps inevitable that the Victorian period running from 1837 to 1901 takes a large chunk of the book. This was a time during which there was a great move to the cities in support of the industrial revolution and a degree of “push” with the Inclosures Acts, Slum dwelling grew common, sanitation and urban clearances were initiated to relieve the slum conditions and the suburbs grew – supported first by omnibuses and then by railways. Although overcrowding and insanitary conditions were recognised early in the Victorian period addressing them took some time, with major improvements in the sewerage system happening towards the end of the 19th century. Often “improvement” schemes were more about sweeping aside the poor with no regard as to where they might live.

Towards the end of the Victorian period the suburbs started to grow, enabled by omnibus and then rail transport. It is at this time that semi-detached properties started to become common. The early suburbs gave me the impression of more rural aspects than modern suburbs. Some of the homes built in the late 19th century are very similar to those built in great numbers between the wars. It was only after the First World War that state intervention in building homes became widespread, the green shoots of this movement started in the late 19th century.

Sadly there is little scope for me to apply these methods to my own homes, I have nearly always lived in late sixties or seventies homes oddly they have had house numbers clustered around 30. In Bristol, as a student I lived in a basement flat close to the developments by Benjamin Stickland built around 1850.

I found A house really readable, it would be a great starting point if you were looking into the history of your own house or were just interested to understand how the domestic built environment came into being in the United Kingdom.