I am about to take on a couple of data science students from Lancaster University for summer projects, from past experience I always spend some time at the beginning of such projects explaining how I work with the expectation that they will at least take some notice if not repeat my methodology exactly. This methodology evolves slowly over time as I learn new things and my favoured technologies change.

Typically I develop on a Windows laptop but I use the git-bash prompt as my shell for typing in commands – this is a Linux-like terminal which I adopted after working with developers who mainly used Linux and also because I was familiar with the Unix style commandline from before the time on Linux. You can do a lot from the commandline in data science – Data Science at the Command Line by Jeroen Janssens is an excellent introduction.

I use Docker containers a bit to spin up local versions of services which are difficult to run on Windows (things like Airflow and Linkedin DataHub), some people develop entirely inside Docker containers to reduce dependency issues and make deployment of code easier.

I work pretty much entirely in Python for data processing and analysis although I generate CSV files which I load to Tableau for visualisation. I tend not to try complex processing in Tableau since I find the GUI inconvenient and confusing for such work. I use the Anaconda distribution of Python, originally because I liked that it came packaged with a load of useful libraries for data science and it handled virtual environments and installation of more tricky packages better than plain Python. It may be worth revisiting this decision. I have recently shifted my code to Python 3.9.

For a piece of work I will usually set up a Python project which can be “installed”. This blog post explains a standard structure for Python projects. I aim to use Python virtual environments on a per project basis but sometimes I fail. Typically, I will write Python modules that provide functions but also have a simple command line interface which takes two or three positional parameters. You can see this in action in the git repo here which I share as a template for myself and others!

To date I have picked up commandline arguments using sys.argv I should probably use one of the libraries to make these commandline interfaces better, there is a blog post here which compares the built-in argparse library with click and docopt. I think I might check out click for future projects.

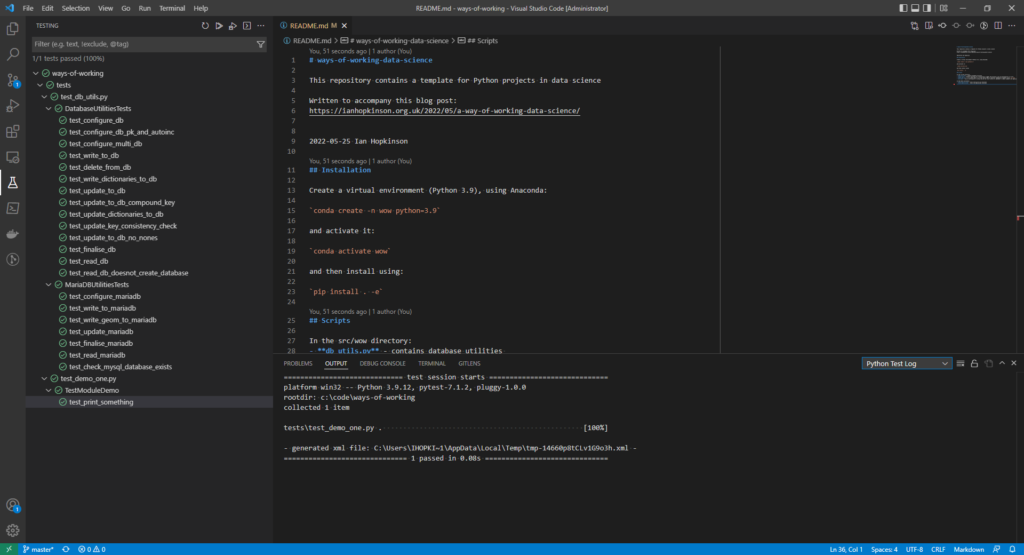

As well as running commandline scripts I use tests to develop analysis, as well as being good software development practice, test runners make a convenient way to run arbitrary functions in a code base. I prefer to use the unittest built-in library but I’ve started using pytest for a recent project. I wrote a blog post about writing tests, since I wrote it I have learned about test mocks and pytest’s fixture functionality.

I have a library of general utilities for interacting with databases, setting up logging and writing dictionaries which I wrote because I found I was doing these things repeatedly and making my own library allowed me to forgot some of the boilerplate code required to do these things. The key utilities are included with the repo attached to this blog.

I’ve been using Visual Code as my editor for some time now, I prefer not to use full blown IDEs because I find they present more functionality than I can cope with. I think this is as a result of coding in Java using Eclipse and C# .net in Visual Studio. In any case Visual Code starts as a nice enough code editor but has been sneaking in more IDE functionality via extensions.

The extensions I use heavily in Visual Code are Python and Pylance – the Python language server provides type-hinting support. I wrote about type-hinting in Python here. I also use Rainbow CSV for when I am editing or viewing CSV files.

I could use Visual Code for accessing git, my preferred source control system, but instead I use GitKraken which has a very nice GUI interface. Since I am usually working by myself my git usage is very simple, I typically have one branch onto which I make many small commits. I have recently started working with a team where I am using feature-based branches which get merged by pull requests – this was a bit of a culture shock.

As a result of working with other people on a new project I have started using some technologies which I will just mention here. I run the black formatter, as well pylint and flake8. Black just reformats my code files when I save them and can largely be ignored. Flake8 is fairly easy to satisfy although I spent a lot of time addressing line length issues. Pylint generates quite a few warnings which I attend to but sometimes ignore.

I have also started using Make files and Azure Devops pipelines for running common tasks on my code (tests, cleanup, setting up infrastructure, linting).

Outside technology, I have a very long established method of working using a monthly Word document as a notebook, I describe it here. I tend to prefix file names with ISO8601 format dates (2022-05-22) this means that if I created a Tableau workbook or an Excel worksheet I can link it easily to what I was writing in my notebook and the status of the appropriate git repo at that point in time.

I’ve incorporated all the code related elements mentioned above in this ways-of-working-data-science git repository.

Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu and How it Changed the World by Laura Spinney

Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu and How it Changed the World by Laura Spinney