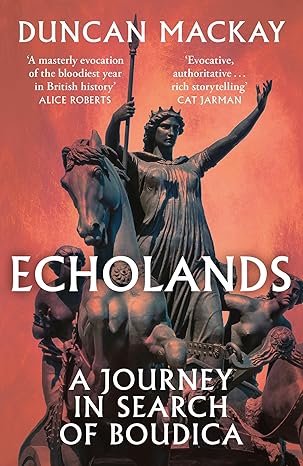

One book leads to another, after reading about prehistoric Britain I was interested in what came next – the Romans. Someone on social media suggested Echolands by Duncan MacKay subtitled A Journey in Search of Boudica. This is an apt description, the book is part travelogue, part history book. MacKay describes his journey following the path of Boudica to Colchester, London, Verulamium and to a final Great Battle with Paulinus, the Roman governor of Britain at the time. He travels variously by car, foot and bicycle. Initially I was sceptical of this style but it is rather compelling – the journey acts as a kind of mnemonic map for the historical facts conveyed.

Britain’s written history starts with Caesar’s expeditions in 54BC and 55BC. It was written not by the British but the Romans. Caesar did not conqueror any territory in Britain but extracted tribute from one king, and set up another as a client. This seems to have started a slow Romanisation of Britain with the local elites seeing the luxuries available in the Empire, and their sons going to Rome for a civilised upbringing (it isn’t quite clear if this export was voluntary). Britain already made some use of coinage which I find intriguing in a supposedly pre-literate society. There is scant archaeology from this period but a number of hordes of valuable items have been recovered.

The action then moves onto the Roman invasion in 43AD, over a 40 year period something like 250,000 Britons would lose their lives to the Romans, and it is likely 250,000 more were taken into slavery – this is from a population of around 2 million. The initial invasion force was around 40,000. The conquest was a slow process with some outright military victories and alliances or arrangements with the existing kingdoms as well as a lengthy and brutal campaign in Wales. The subjugation of Wales was to take until 51AD, veterans of this campaign retired to Camulodunum (Colchester) where they formed a colony. Relevant from this period is King Prasutagus of the Iceni tribe, whose wife was Boudica.

On his death Prasutagus in 59AD attempted to make his wife, Boudica, heir to his kingdom alongside Rome. Rome did not take kindly to this, Boudica was whipped and her two daughters raped. Subsequent events are recorded by Tacitus in The Annals (English version here, original latin here). There are also some references in Cassius Dio’s Roman History (English version here). These are relatively brief accounts and much of the understanding of events turns on a couple of sentences. Apparently Romans referred to us as Britunculi – “little Britons”!

In 60AD Boudica and her allies attacked the Camulodunum colony, killing effectively all of its inhabitants and burning it to the ground. The destruction can be seen in the archaeological record, and in fact burning has preserved more of the wattle and daub and other wooden structures than would normally be found. The final redoubt of the Roman colonists was the extravagant Temple of Claudius which was besieged for two days according to Tacitus.

On hearing news of the massacre the 9th Legion from set out towards Camulodunum via Cambridge. MacKay thinks they started from Longthorpe (outside Peterborough) whilst others suggested they started from their main garrison in Lincoln. This is where MacKay first takes to the road in earnest, travelling along the A14 to Cambridge, at the time this was the Via Devana (The Chester Road). MacKay is keen on his caligae (Roman hobnailed sandals) with which he walks some of the route. We lived in Cambridge for nearly 10 years and I know the A14 well, now we live in Chester. So this leg of the journey strikes a cord. The 9th legion were massacred somewhere outside Camulodunum, MacKay suggests the Colne Valley as a likely location for the ambush. This seems to be largely on the basis of where he supposed they were coming from and the local geography. There is no archaeological evidence for the battle.

In the meantime the Roman governor of Britain at the time, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, is invading Anglesey where the last Welsh resistance is holding out. Tacitus notes of the women in the opposing forces ranks:

In the style of Furies, in robes of deathly black and with dishevelled hair, they brandished their torches; while a circle of Druids, lifting their hands to heaven and showering imprecations, struck the troops with such an awe at the extraordinary spectacle that, as though their limbs were paralysed, they exposed their bodies to wounds without an attempt at movement.

Despite this they are beaten easily by Paulinus’s legionnaires. MacKay travels to the vicinity of RAF Valley on Anglesey to start his retrace of Paulinus’s rapid trip south to face Boudica. We spent our summer holiday in Rhosneigr – a couple of miles away! The site is interesting because a number of artefacts were discovered in the lake there. One of them, a slave chain, was actually used by workers in the 1940s conducting a peat excavation operation and survived the experience remarkably well!

It is thought that Paulinus prepared his invasion boats (likely flat bottomed barges), in Chester and on his trip back to London – on news of Boudica’s rebellion – at least part of his force probably sailed back to Chester. Paulinus then takes his force south to London likely heading down towards Wroxeter (near Shrewsbury) along the now vanished start of the Watling Street Roman road before following it onwards to London along the still existing line of Watling Street. MacKay follows this route by car stopping on the outskirts of London to travel by rail and foot to the area of Monument, the centre of Roman London.

In 60AD London was a thriving trading centre but does not appear to have been an important town to the Romans from an administrative point of view, furthermore it did not have significant defences at the time so on his arrival Paulinus decided to abandon London to Boudica’s forces who were heading down from Colchester. He departed with those able and willing to follow, some may have taken refuge from Boudica on boats in the Thames. In any case London was comprehensively burnt by Boudica’s forces. Paulinus then headed up toward Veralumium (near modern day St Albans) which Boudica also destroyed.

That was the limit of Boudica’s rebellion, MacKay spends some time visiting potential locations for the final Great Battle of which Tacitus just says “…a position approached by a narrow defile and secured in the rear by a wood…“. This location has been the subject of much discussion with locations up into Warwickshire finding favour. MacKay appears to have decided on Windridge Farm close to Veralumium on the basis of the geography of the area, the proximity to a know location for Boudica and the discovery of clusters of Roman slingshot . Wherever it was Tacitus claims 80,000 of Boudica’s forces were killed in a single engagement, for comparison the first day of the Battle of the Somme saw 20,0000 British troops died. This ended Boudica’s rebellion and Tacitus says she died by her own hand afterwards.

The Roman’s lost a similar number of soldiers and civilians during the rebellion. What surprised me is despite these huge battles in the Colne Valley, on Anglesey and close to St Albans there is minimal archaeological evidence from these sites. Part of the problem is no doubt the uncertainty of their location, but also 80,000 dead on the ground surface would likely disappear over a period of a few years. Armour and weapons were valuable and would have been cleared from the battle field. MacKay references reports from other Roman battles, the Indian Rebellion and a battle between the British and Zulus, as to how such locations appeared after a few months or years.

The Romans were brutal occupiers, as evidenced by their own historians, and the carved columns they raised in honour of victorious generals. Boudica’s forces were brutal too. It would have taken the Romans a number of years to recover from the rebellion, furthermore the local population struggled through famine in the aftermath of the rebellion (Tacitus puts the blame for this squarely on the British).

I enjoyed this book, I thought the combination of travelogue and history worked really well and by chance I was familiar with a number of the locations MacKay visits.