Author's posts

Nov 12 2021

Book review: Empireland by Sathnam Sanghera

A return to reading about race with Empireland by Sathnam, subtitled How Imperialism Has Shaped Modern Britain. I think the best way of thinking about this book is as a perspective on the British Empire and its impact on present day Britain by a British Sikh. Although the coverage is global there is a focus on India, which reflects Sanghera’s background. I’m used to reading history by white British or American authors, so this is a refreshing change.

A return to reading about race with Empireland by Sathnam, subtitled How Imperialism Has Shaped Modern Britain. I think the best way of thinking about this book is as a perspective on the British Empire and its impact on present day Britain by a British Sikh. Although the coverage is global there is a focus on India, which reflects Sanghera’s background. I’m used to reading history by white British or American authors, so this is a refreshing change.

The signs of Empire are all around us, not least in the multicultural, multi-ethnic society we find in Britain which impacts our food, our religious observances and our art. A range of quintessentially British companies had their origins in the trade with India such as Shell who originally sold shells from India! Or Liberty original founded for the India trade. There are also a range of processed foods which were developed for the empire, to remind the colonists of home or taken up following colonial origins (rum, pale ale, madeira, gin and tonic). There is some argument that our welfare state had its origins in Empire, in providing "men fit to fight" which was a concern after the Boer War. We also borrowed a significant number of words into English from the empire: bungalow, shampoo, zombie, toboggan…

The Empire, and Imperial history is not clear cut, there are two very broad phases – the American and contemporary phase and the 19th century India and Africa phase. The Empire was not the result of a strategic plan, or governed in a unified manner, in contrast to the Roman Empire. As John Robert Seeley said: "We seem, as it were, to have conquered and peopled half the world in a fit of absence of mind". It seems also that the Empire was not front of mind for the British public for almost its entire span, in the days before a global media with relatively few British people involved with the Empire in Britain or even in the Empire this is perhaps unsurprising.

A recurring theme is how British actions in the empire were criticised at the time, on issues like the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, and the looting of Tibet. Key figures in the Empire, like Robert Clive and Cecil Rhodes were similarly criticised. The rehabilitation of Edward Colston is a case in point – he was not greatly celebrated during his life and the subscription to raise his statue some 200 years after his death was not filled. It is only with the recent en-harbouring of his statue that he has gained support. History that seeks an unalloyed positive view of the Empire just isn’t history.

Looting gets a whole chapter of its own, it focuses on the case of Tibet which was invaded by the British in 1903/4 – interestingly the invasion was commonly referred to as the "British Expedition to Tibet" or the "Younghusband expedition to Tibet" – note the rather passive language. It is clear that looting was seen as part of military operations and was formalised. There is a degree of greyness in the process since troops were on occasion censured for looting, and there were budgets for the purchase of artefacts. However, there were clear processes for the handling of artefacts looted during invasions and the sums set aside for purchasing artefacts were completely incompatible with the amount of loot returned to Britain. In Africa human body parts were taken by British soldiers as trophies, something which caused disgust in Britain at the time.

The sad thing is that most of the looted artefacts in British museums are not actually on display, and in the more distant past they were scarcely valued at all. Sanghera points out that the British establishment finds it impossible to return looted artefacts from British museums to their rightful homes but has quite the opposite attitude to people with established lives and families, as long as their skin is dark.

Immigration was often at invitation, citizens of the British Empire were just that but whilst white members of the Commonwealth have always had a welcome in Britain, those of colour have not. Conversely Britain has a large emigrant – outbound – population. It is part of the deal. Sanghera writes a bit about Britons abroad, the Brit transplanting their lifestyle to Spain is seen as a continuation of the colonial times.

Sanghera talks about racism and white supremacy in the British Empire. This is pretty explicit, the leading figures in the Empire were very clear that they saw the white British as superior and indigenous populations as naturally inferior, in need of the firm hand of white rule. White rule, sometimes meant massacre or even genocide, as was the case for the indigenous Tasmanian population.

Sanghera ends on a somewhat positive note, although Britain is not at the forefront, countries like Germany, France and the US have started talking about the return of looted artefacts, reparations for slavery, and some degree of contrition for their actions during their colonial period. The British government is trailing in this, although the public Black Lives Matters protests, and private initiatives to return looted artefacts, and discuss more frankly our troublesome past are taking place.

I think this was a useful step on my journey in understanding my country, and all the people that live here.

Oct 17 2021

Book review: Much ado about mothing by James Lowen

Excited by my recent purchase of a trail camera to observe the wildlife in our backgarden (mainly foxes), I was draw to moths (and mothing), like a moth to a flame or a pheromone lure (it’s the modern way). Much Ado about Mothing by James Lowen speaks of a similar attraction, structured into a book.

Excited by my recent purchase of a trail camera to observe the wildlife in our backgarden (mainly foxes), I was draw to moths (and mothing), like a moth to a flame or a pheromone lure (it’s the modern way). Much Ado about Mothing by James Lowen speaks of a similar attraction, structured into a book.

Much ado about mothing is based around the idea of finding 120 target months over the space of a year. It is divided into chapters that track through the seasons and through different ecosystems such as heaths, beaches, salt marshes, forests and so forth. I was pleased to see my home county of Dorset, particularly Portland and the heaths around Purbeck where I grew up, featuring heavily. Over the period of a year Lowen ran a light trap in his back garden in Norfolk on 151 nights, capturing 15,000 individuals from 466 species as well as travelling far and wide in Britain to find moths.

Moths are the super-group in which butterflies are a subset. They are more numerous in terms of species than butterflies by a large margin – perhaps 40 times as many moth species as butterflies. Many of the females are flightless (making them more difficult to find). 90% of moths are nocturnal.

Unlike butterflies, moths are quite docile when trapped and can be handled. The Victorians used sugar and wine mixtures on ropes ("roping") to trap their moths, as the 20th century progressed it became possible to use portable lights and most recently pheromone lures to trap moths. Pheromone lures are used in crop protection and are specific to a species, they mimic the pheromones that females emit to attract males.

As well as the moths with which we might be familiar there are innumerable micromoths typically with only a Latin name, there’s a discussion amongst moth-ers on how (and if) to give them "common" names.

It seems many moth-ers got there from birdwatching, and many RSPB centres double up as centres for mothing. Perhaps it is the easy abundance of moth species which attracts them and the rather better accessibility than birds – you can keep moths in your fridge to share with fellow moth-ers! Around the country there are a number of conservation projects focused on moths these seem to be coordinated by the charity, Butterfly Conservation.

The picture for moths as a group is mixed, many species are in decline as a result of habitat loss. In addition to draining of marshlands, agriculture and rising temperatures, many have very specific host plants, so the loss of the host plant leads the loss of the moth. I wonder why this specificity is favourable from an evolutionary point of view. There are new arrivals though, and territories expanding as temperatures rise.

I found myself Googling pictures of the moths mentioned, there are colour photos of some of the moths but they are all bundled together in the centre of the book. Lowen works hard to describe moths in many varied and interesting ways. You might want to follow the @BritishMoths twitter account for a regular fix of moth content. You can get an overview of British moth species on the Butterfly Conservation A-Z page, species mentioned in Much ado include Clifden Nonpareil, Elephant Hawk-moth, Kentish Glory, New Forest Burnet, Oak Eggar, Buff-tip and Merveille du Jour. I recommend this page as a perfect supplement to the book!

Much ado about mothing is more in the style of a travelogue than a nature book but I suspect this means it sneaks in many facts about moths which you wouldn’t find by reading a moth identification guide. I have learnt that Batesian mimics are those species that mimic other, toxic, species whilst Mullerian mimics are genuinely toxic. This I learnt in the discussion of Clearwing moths, a group of moths that mimic wasps.

The other prominent aspect of the travelogue style is the people he meets, mothing seems quite a sociable sport. Sometimes this is because the fellow moth-er is a warden at a nature reserve but other times it is a group of friends, or moth enthusiasts who share sightings and information – as well as camping out in all manner of locations to look after moth lights.

I think Much ado has done its job since I’m now keen to start my own mothing. I bought a telescope as summer approached – it doesn’t get dark until really late and we had a small child – so observing the night sky was tricky. I’ll not make that mistake again! Moths are most common during the summer months, there is little point in buying a moth trap for Christmas so I will get mine in late Spring.

Oct 03 2021

Book review: Audio Production Basics with Ableton Live by Eric Kuehnl

I started playing guitar a few years ago, and acquired an electronic drum kit a year or so later, as well as a keyboard and a ukulele. My wife has a bass guitar, and my son recently brought home a clarinet from school (in what can only be described as an act of war on the part of his teacher!).

I started playing guitar a few years ago, and acquired an electronic drum kit a year or so later, as well as a keyboard and a ukulele. My wife has a bass guitar, and my son recently brought home a clarinet from school (in what can only be described as an act of war on the part of his teacher!).

I’ve been playing with computers for 40 years so it seemed natural to put the two things together, also I follow Paul David’s Guitar channel and when he came to talk about looping he skipped the whole looper pedal method and went straight to demonstrating looping in Ableton Live, a "digital audio workstation" (DAW). It turns out Ableton, and comparable products, are fearsomely complicated so being a bookish sort of person I bought Audio Production Basics with Ableton Live by Eric Kuehnl to work out how to use it.

The book starts with some introductory material on computers and storing files, which is a bit basic. Before talking a little bit about different DAWs, including selecting gear for your music studio. It turns out there are audio interfaces, MIDI instruments, MIDI control surfaces as well as microphones.

Next up are some words on the overall scheme for audio recording, here and elsewhere I was grateful for a background in physics since the physics of sound is a bit of a feature for audio production. It clearly isn’t a problem if you don’t have a background in physics.

The introduction to the MIDI standard for communicating between music devices brought back memories for me, MIDI was invented in the early eighties when I was avidly reading computer magazines where I witnessed its inception.

For a long time audio production software, like Ableton, was very expensive but now it is much cheaper. I’m currently in the evaluation period for Ableton Live (a generous 90 days) but the introductory version is only £69. I’ve spent similar sums on a little MIDI controller and audio interface. I should probably get a decent microphone and stand, and now I’m coveting blingy MIDI control surfaces.

Finally we get on to the specific features of Ableton Live, about half way into the book! This is slightly unfair, we do get some glimpses before this. I found the book was good for structuring wider enquiry, one of the issues with a complex system like Ableton Live is not having the words to investigate (Google) further, and to be honest the problem once you have googled you are often faced with a screen-full of videos to watch. Audio production Basics gives you some of the vocabulary to ask useful questions, and I found reading it led me to grasping some important concepts. Also I discovered the videos Ableton make are very good.

For a long time I was confused because I thought that the Session View and Arrangement Views in Ableton Live were just that, views onto the same piece of audio data, but that is not the case. The Session View allows you to organise clips, often loops, sequence sets of clips together which you can perform live, with the option to record into an Arrangement view. It seems the Session View was originally the unique feature of Ableton Live, and is used on stage by performers.

The second useful concept is the Return Track, accessed for each channel using the Sends area of the control panel – you can see why it is tricky to come across the concept – it is called one thing in one place and another elsewhere. I suspect for people with a background in audio production the idea of Sends and Returns is commonplace. For a guitarist a Return Track is a bit like a pedal, you can route sound from each of your Audio/MIDI tracks through Return Tracks like Delay and Reverb.

Finally, if you search around the internet you’ll find a lot of beginners worried about how loud individual tracks sound. This has a couple of causes, sometimes it is because audio sources have not been processed by the audio interface correctly but often it is a misapprehension as to what the DAW does – it is not really a playback device. Individual tracks may sound quiet because ultimately they are going to be combined with a number of other sources, and if they were all "loud" then it would be overwhelming.

I have mixed feelings about this book, it takes a while to get onto Ableton specifics, and it feels like it doesn’t provide complete coverage. On the other hand working through the examples (something I rarely do) has introduced me to a lot of functionality, and is easier to my mind, than following Youtube videos.

Sep 17 2021

Python Documentation with Sphinx

I’ve been working on a proof of concept project at work, and the time has come to convert it into a production system. One of the things it was lacking was documentation, principally for the developers who would continue work on it. For software projects there is a solution to this type of problem: automated documentation systems which take the structure of the code and the comments in it (written in a particular way) and generate human readable documentation from it – typically in the form of webpages.

For Python the “go to” tool in this domain is Sphinx.

I used Sphinx a few years ago, and although I got to where I wanted in terms of the documentation it felt like a painful process. This time around I progressed much more quickly and was happier with the results. This blog post is an attempt to summarise what I did for the benefit of others (including future me). Slightly perversely, although I use a Windows 10 laptop, I use Git Bash as my command prompt but I believe everything here will apply regardless of environment.

There are any number of Sphinx guides and tutorials around, I used this one by Sam Nicholls as a basis supplemented with a lot of Googling for answers to more esoteric questions. My aim here is to introduce some pragmatic solutions to features I wanted, and to clarify some thing that might seem odd if you are holding the wrong concept of how Sphinx works in your head.

I was working on a pre-existing project. To make all of the following work I ran “pip install …” for the following libraries: sphinx, sphinx-rtd-theme, sphinx-autodoc-typehints, and m2r2. In real life these additional libraries were added progressively. sphinx-rtd-theme gives me the the popular “Readthedocs” theme, Readthedocs is a site that publishes documentation and the linked example shows what can be achieved with Sphinx. sphinx-autodoc-typehints pulls in type-hints from the code (I talked about these in another blog post) and m2r2 allows the import of Markdown (md) format files, Sphinx uses reStructuredText (rst) format by default. These are both simple formats that are designed to translate easily into HTML format which is a pain to edit manually.

With these preliminaries done the next step is to create a “docs” subdirectory in the top level of your repository and run the “sphinx-quickstart” script from the commandline. This will ask you a bunch of questions, you can usually accept the default or provide an obvious answer. The only exception to this, to my mind, is when asked “Separate source and build directories“, you should answer “yes“. When this process finishes sphinx-quickstart will have generated a couple of directories beneath “docs“: “source” and “build“. The build directory is empty, the source directory contains a conf.py file which contains all the configuration information you just provided, an index.rst file and a Makefile. I show the full directory structure of the repository further down this post.

I made minor changes to conf.py, switching the theme with html_theme = ‘sphinx_rtd_theme’, and adding the extensions I’m using:

extensions = [

'sphinx.ext.autodoc',

'sphinx_autodoc_typehints',

'm2r2',

]

In the past I added these lines to conf.py but as of 2022-12-26 this seems not to be necessary:

import os

import sys

sys.path.insert(0, os.path.abspath('..'))

This allows the Sphinx to “see” the rest of your repository from the docs directory.

The documentation can now be built using the “make html” command but it will be a bit dull.

In order to generate the documentation from code a command like: “sphinx-apidoc -o source/ ../project_code“, run from the docs directory will generate .rst files in the source directory which reflect the code you have. To do this Sphinx imports your code, and it will use the presence of the __init__.py file to discover which directories to import. It is happy to import subdirectories of the main module as submodules. These will go into files of the form module.submodule.rst.

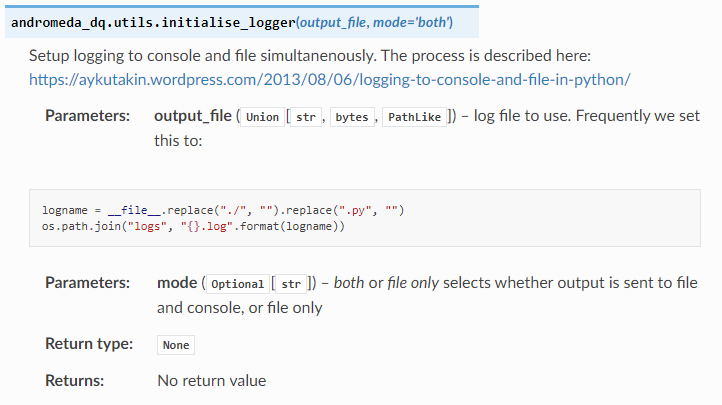

The rst files contain information from the docstrings in your code files, (those comments enclosed in triple double-quotes “””I’m a docstring”””. A module or submodule will get the comments from the __init__.py file as an overview then for each code file the comments at the top of the file are included. Finally, each function gets an entry based on its definition and some specially formatted documentation comments. If you use type-hinting, the sphinx-autodoc-typehints library will include that information in documentation. The following fragment shows most of the different types of annotation I am using in docstrings.

def initialise_logger(output_file:Union[str, bytes, os.PathLike], mode:Optional[str]="both")->None:

"""

Setup logging to console and file simultanenously. The process is described here:

Logging to Console and File In Python

:param output_file: log file to use. Frequently we set this to:

.. highlight:: python

.. code-block:: python

logname = __file__.replace("./", "").replace(".py", "")

os.path.join("logs", "{}.log".format(logname))

:param mode: `both` or `file only` selects whether output is sent to file and console, or file only

:return: No return value

"""

My main complaint regarding the formatting of these docstrings is that reStructuredText (and I suspect all flavours of Markdown) are very sensitive to whitespace in a manner I don’t really understand. Sphinx can support other flavours of docstring but I quite like this default. The docstring above, when it is rendered, looks like this:

In common with many developers my first level of documentation is a set of markdown files in the top level of my repository. It is possible to include these into the Sphinx documentation with a little work. The two issues that need to be addressed is that commonly such files are written in Markdown rather reStructuredText. These can be fixed by using the m2r2 library. Secondly the top level of a repository is outside the Sphinx source tree, so you need to put rst files in the source directory which include the Markdown files from the root of the repository. For the CONTRIBUTIONS.md file the contributions.rst file looks like this:

.. mdinclude:: ../../CONTRIBUTIONS.md

Putting this all together the (edited) structure for my project looks like the following, I’ve included the top-level of the repository which contains the Markdown flavour files, the docs directory, where all the Sphinx material lives, and stubs to the directories containing the module code, with __init__.py files.

. ├── CONTRIBUTIONS.md ├── INSTALLATION.md ├── OVERVIEW.md ├── USAGE.md ├── andromeda_dq │ ├── __init__.py │ ├── scripts │ │ ├── __init__.py │ ├── tests │ │ ├── __init__.py ├── docs │ ├── Makefile │ ├── make.bat │ └── source │ ├── _static │ ├── _templates │ ├── andromeda_dq.rst │ ├── andromeda_dq.scripts.rst │ ├── andromeda_dq.tests.rst │ ├── conf.py │ ├── contributions.rst │ ├── index.rst │ ├── installation.rst │ ├── modules.rst │ ├── overview.rst │ └── usage.rst ├── setup.py

The index.rst file pulls together documentation in other rst files, these are referenced by their name excluded the rst extension (so myproject pulls in a link to myproject.rst). By default the index file does not pull in all of the rst files generated by apidoc, so these might need to be added (specifically the modules.rst file). The index.rst file for my project looks like this, all I have done manually to this file is add in overview, installation, usage, contributions and modules in the “toctree” section. Note that the indentation for these file imports needs to be the same as for the preceding :caption: directive.

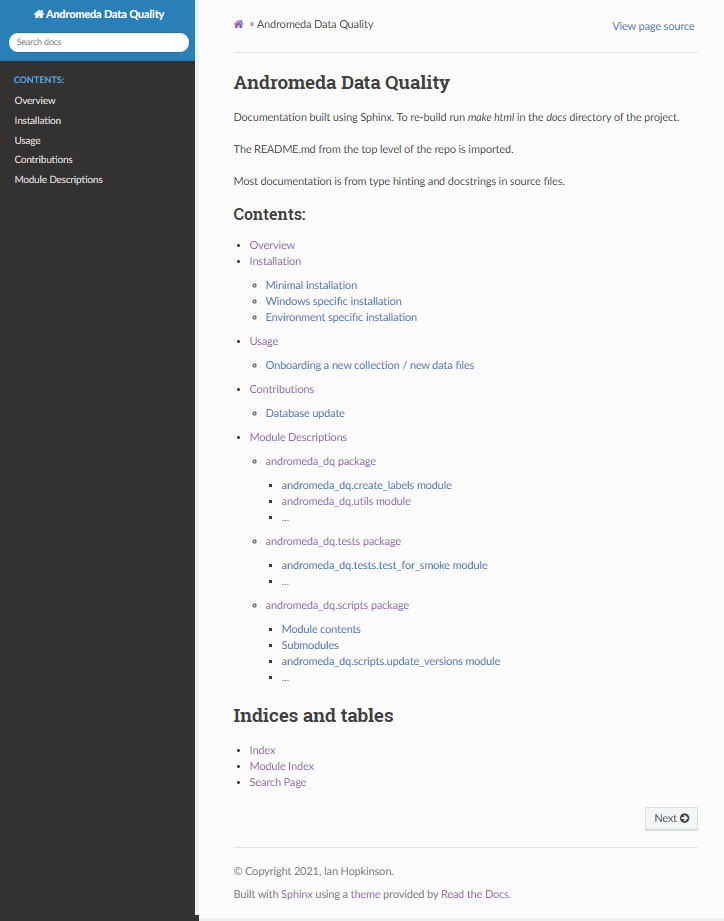

.. Andromeda Data Quality documentation master file, created by sphinx-quickstart on Wed Sep 15 08:33:59 2021. You can adapt this file completely to your liking, but it should at least contain the root `toctree` directive. Andromeda Data Quality ====================== Documentation built using Sphinx. To re-build run `make html` in the `docs` directory of the project. The OVERVIEW.md, INSTALLATION.md, USAGE.md, and CONTRIBUTIONS.md files are imported from the top level of the repo. Most documentation is from type-hinting and docstrings in source files. .. toctree:: :maxdepth: 3 :caption: Contents: overview installation usage contributions modules Indices and tables ================== * :ref:`genindex` * :ref:`modindex` * :ref:`search`

The (edited) HTML index page for the documentation looks like this:

For some reason Sphinx puts the text in the __init__.py files which it describes as “Module Contents” at the bottom of the relevant package description, this can be fixed by manually moving the “Module contents” section to the top of the file in the relevant package rst file.

There is a little bit of support for Sphinx in Visual Code, I’ve installed the reStructuredText Syntax highlighting extension and the Python Sphinx Highlighter extension. The one thing I haven’t managed to do is automate the process of running “make html” either on commit of new code, or when code is pushed to a remote. I suspect this will be one of the drawbacks in using Sphinx. I’m getting a bit better at adding type-hinting and docstrings as I code now.

If you have any comments, or suggestions, or find any errors in this blog post feel free to contact me on twitter (@ianhopkinson_).

Sep 11 2021

Book review: Precolonial Black Africa by Cheikh Anta Diop

My next book follows on from reading Black and British by David Olusoga. It is Precolonial Black Africa by Cheikh Anta Diop. I was looking for an overview of African history from an African perspective. Diop’s relatively short book focuses on West Africa. It turns out he is a very interesting figure in himself, building several political parties, doing research in history as well as physics and chemistry and having a university named after him. Some of his ideas on African history are controversial (you can see the wikipedia page relating to him here).

My next book follows on from reading Black and British by David Olusoga. It is Precolonial Black Africa by Cheikh Anta Diop. I was looking for an overview of African history from an African perspective. Diop’s relatively short book focuses on West Africa. It turns out he is a very interesting figure in himself, building several political parties, doing research in history as well as physics and chemistry and having a university named after him. Some of his ideas on African history are controversial (you can see the wikipedia page relating to him here).

The core of the controversy is two fold, one is his claim that ancient Egyptians were black, and the second is that there is a historical unity in West Africa civilisation with migration from the east of Africa populating the continent. The basis for this thesis relies quite heavily on similarities in totemic names across the region as well as cultural similarities. These days there is some support for the migration of populations out of the Nile basin to West Africa from DNA evidence.

Most of the discussion in this book is oriented around the area of West Africa where Diop grew up, in Senegal, with some mentions of Eygypt and Sudan. Diop draws parallels in the internal organisations across the empires of Ghana, Mossi, Mali and Songhai. The Empire of Ghana stretched beyond the boundaries of the modern country, and stood for 1250 years. Mossi was to the east and south, in the area of modern Burkino Faso, Mali and Songhai were a little to the north encompassing the modern Timbucktu. Looking at wikipedia these empires appear to have overlapped to a degree both in time and space. Precolonial Black Africa covers the period from about 300AD to the 17th century although it does not make much reference to dates.

There is almost no mention even of the area of Nigeria, a little to the east, or Southern Africa. I was nearly half way through the book before I realised that Sudan referred to two different places: Sudan the modern state in North East Africa, and the Sudan Empire which stretches across the southern margin of the Sahara in the West of Africa.

The books starts with a description of the caste system, emphasising the two-way nature of the system and contrasting it to a degree with the caste system in India.

Precolonial Black Africa contrasts Africa with Europe, in the period covered by the book Europe was based on city-states which evolved into feudal structures, with Roman geographical divisions, where defence from marauders by the lord in the castle was important. Land ownership was core of this political system whereas Africa evolved more along Egyptian lines which saw countries divided into regions with regional governance and no tradition of land ownership.

These empires were led by kings with a small cabinet of advisors who had both a regional responsibility and a specialism (like a minister for finance, or the army). Although not republics, nor democratic in the modern Western sense, Diop claims that these governments were more representative than their Western European equivalents of the time.

The technological expertise of the ancient Romans and Greeks was carried through the Middle Ages by the Arab world. It is no coincidence that Spain was once a technology leader, given the Muslim rule of Spain. Islamization of West Africa is a recurring theme of the book, and Arab writers feature regularly in the lists of sources for the early history of Africa. Islam was important in education through to the present day, this is in part responsible for slowed technological progress in the region. Islamic schools did not place a great emphasis on what they consider pagan history, nor so much on modern science.

Precolonial Black Africa covers technology relatively briefly, mentioning architecture and the Great Zimbabwe – a significant stone-built city in present day Zimbabwe whose early excavation was plagued by the then Rhodesian governments view that it could not be constructed by Black Africans. Coins, and metalworking are also mentioned – West Africa made relatively little use of the familiar coinage of European. Gold dust was used as currency, as were Cowrie shells. The Benin Bronzes dating from the 13th century demonstrate there was significant metalworking skill in West Africa (the Bronzes are currently in the news as the UK refuses to return them to Benin). Little of technology and writing seems to have survived from precolonial times, I suspect this is a combination of the environment which is not conducive to the preservation of paper (or even metal), successive colonisations by Islam and then Europeans and relatively little archaeological activity.Trade seemed quite significant across West Africa, even in the absence of conventional coinage.

The interesting thing reading this book is the contrast with flaws that Western history has had in the past, being focussed on great men, the idea of the natural superiority of the white man, and leaning heavily on Classical heritage for legitimacy. I suspect these points of view are generally not prevalent in modern academic history but they certainly hold sway with the current UK government and a coterie of right-wing historians. To a degree Diop suffers the same types of prejudices but from a different perspective – the superiority of the Black African. My view of African history is still heavily influenced by those old Western European foundations.

After a rocky start I came to enjoy this book, I found the book alien in a couple of respects firstly in its discussion of history from an African perspective, and also simply that it is African history. What I know of Africa is largely through a colonial lens.