Author's posts

Feb 13 2012

Bad at games

A little while back I was sitting down with colleagues for coffee, we were bemoaning the grim time we had at school in PE (physical education) lessons. My colleagues and I are all scientists, we excelled in other areas at school. For much of my school life I abhorred “games” lessons, if there were teams to be picked then I would be second to last to be selected – just before the fat kid in the class. I have a clear memory of members of my own team attacking me on the rugby pitch. These experiences were common to my colleagues. It isn’t even that I am particularly unfit, it was simply that I didn’t get on with organised team sports or activities; I couldn’t see the point.

My revelation was that there are no doubt a multitude of parallel groups that said the same of their maths lessons, physics lessons, English lessons… They did not excel at the activities with which they were presented, they couldn’t see the point of them and ultimately they have found they have little relevance to their vocations but they needed to get something from those lessons.

For me finding the way is simply to go to the gym three times a week at the crack of dawn, engaging in a variety of slightly pointless activities whilst listening to radio 4’s Today program and watching soundless “Heartbeat”. I wish my PE lessons had given me this 30 years ago.

Feb 07 2012

Arrival…

Thomas Samuel was born 5:39am on Saturday 4th February 2012, weighing 6lb 2oz (imperial being the SI unit of measure for babies), the birth was by caesarean section. Baby and mum are both doing well. Here he is only a couple of minutes old:

And now, on the 7th February:

I don’t want to write about the details of the labour, it feels like an invasion of privacy, all I can say is that I now consider women to be heroes and scarily superhuman! I am a very proud dad.

More pictures here.

Jan 29 2012

Chester Cathedral

After 7 years living in Chester I have finally gotten around to visiting the cathedral, actually it took a parental visit to get me over the threshold! It was a cold frosty morning in January when we visited.

I am an atheist, but culturally a Christian one, so in a sense I feel at home. I tend to see cathedrals as medieval moon-shots – endeavours of almost unbelievable scale for the time in which they were constructed. We approached the cathedral from the North, along the city walls. Passing along Abbey Street where we saw this rather skewed gateway:

Charles Kingsley, author of “The Water Babies”, was canon at the cathedral and also founder of the Chester Natural Sciences Society. I will spare you the photo of the blue plaque from which I gleaned this information. On the way into the cathedral, the Cloisters.

You’ll have to forgive me, I’m not too up on the nomenclature for ecclesiastical architectural features, here I am looking down the nave at the altar screen (probably). I’m having problems because of the large variations in light intensity within the scene. There is also some evidence for my problem of always taking photos at a tilt:

A detail in the roof of the nave:

Off the nave is the Consistory Court, this is the Apparitor’s Chair, or maybe it isn’t the information board hedged slightly on this point. The woodwork in the Consistory Court dates from the early 17th century.

This fabulous device is a Gurney Warm Air Stove, installed in the late 19th century. Sir Goldsworthy Gurney, the inventor of the stove, was an interesting chap.

Chester Cathedral was built in stages, based on a monastic Norman church built in 1093, there are some traces of this original building in the North Transept:

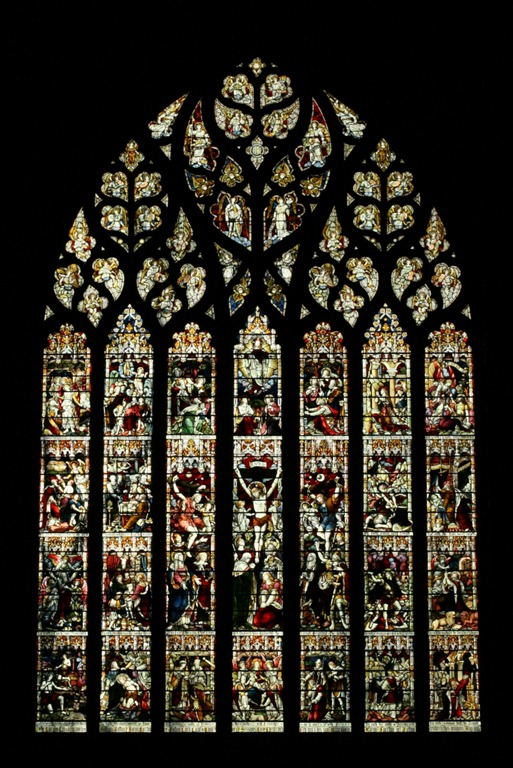

You can’t go to a cathedral without trying to photograph a stained-glass window:

The Choir Stalls, fantastically ornate and clearly difficult to dust:

Frustrated at trying to take photos of difficult to photo things, I thought I’d try something easier: the floor tiles:

That went well, I’ll do some more!

A detail of the ceiling in the the East Nave:

Stone detail in the Cloisters:

Out into the Cloister gardens where there is this fine sculpture by Stephen Broadbent, from here we could hear the croaking of what sounded like ravens, however the little tinkers remained hidden in the heights of the cathedral tower so it was difficult to be sure:

I found cathedral photography rather challenging, the problems are that it’s dark and where it isn’t dark it’s very bright! The human eye-brain combination is terribly clever, it seamlessly accounts for enormous variations in brightness without any great degradation in the user experience. As a photographer this all becomes very obvious. There are workarounds: you can provide your own lighting or you can ramp up the sensitivity of your virtual film (increasing the ISO number), use a tripod (if that’s permitted) to allow longer exposure times, and take multiple shots at different exposures melding them into one shot (known as high dynamic range (HDR) imaging).

High dynamic range imaging and display are hot research areas. The problem on the display side is that if you display a picture of a bright window with a dark surround, even an HDR image, then the surround will “look” too dark. What you need to do is vary the brightness of pixels according to their surrounding pixels – it’s called “tone mapping”, precisely what algorithm you should use to do this is the subject of research.

Most of these shots were taken with my new Canon 50mm f/1.4 although a couple were done with the Canon 28-135mm. Next time I think I’ll try out my ultrawide angle lens: 10-22mm, handy for those smaller corners and perhaps a bit less prone to blur.

Jan 20 2012

More on blogging…

Thanks to Athene Donald* at Occam’s Typewriter for nominating me for a Versatile Blogger Award:

I like to think I am a versatile blogger: I post on books, science, politics, photography, gadgets, and science policy. This is one of those slightly pyramid schemes, in which I’m willing to partake since I fancied listing a few of my favourite blogs. The rules of the scheme are as follows:

- Nominate 15 fellow bloggers (gosh, that’s a lot)

- Inform the Bloggers of their nomination (I could do this in the style of a twitter spammer!)

- Share 7 random things about yourself (see below, tick)

- Thank the blogger who nominated you (see above, tick)

- Post the award badge. (see above, tick)

My blogging nominations:

- The Inelegant Gardener by @happymouffetard. This is my wife’s blog as you can see she has been making me cake, normally she blogs about plants and gardening.

- Shakespeare’s England by @daintyballerina. A blog about early modern England, quoting extensively from contemporary sources.

- Georgian London by @lucyinglis. It does exactly what it says on the tin: a blog about Georgian London from a social history perspective. A bit quiet these days as Lucy is writing a book of the same title.

- The Quack Doctor by @quackwriter. Vignettes of quackery, mainly through the medium of old adverts. Quackwriter aka Caroline Rance is also author of Kill-grief – a story of gin and Chester, both close to my heart.

- Billynojob by @billygottajob. We met him first when he was unemployed, now he’s gotta job! Thoughtful commentary on current affairs.

- The Renaissance Mathematicus by @rmathematicus. Angry ranting about the history of science.

- Reciprocal Space by @Stephen_Curry. Mainly about science policy and processes but also some science.

- Purple Persuasion by @Bipolarblogger, who has bipolar disorder. She blogs about things relating to her illness including handy hints for bystanders, which I value greatly.

- Andromeda Babe’s Blog by @andromedababe. An occasional blog, mostly about entertaining small children which I read anyway but feel will be essential in the near future.

- Stages of Succession by @morphosaurus. Blogs about teaching and a gecko, we “met” because she knew that tunicates “ate their own brains” at the end of their larval stage.

- RealClimate, “Climate Science by climate scientists”. This is what I look for in a science blog, up to date, sufficient detail to satisfy a scientist from outside the field.

- In Pursuit of History by @GentlemanSykes. A history blog, somewhat quiet since he has been freelancing his writing.

- Scott Hanselman’s Computer Zen by @shanselman. Computer things from a Microsoft perspective but also the last point on this.

- A Life in the day of a BASICS doctor. Reports from a British Association for Immediate Care doctor, harrowing and deeply moving.

- Zygoma by @PaoloViscardi. Mainly mystery objects from the Horniman Museum (on a Friday).

Perhaps a little surprisingly I don’t follow many science blogs, I get my science fixes from New Scientist, Nature, Physics World, and Communications of the ACM, three of them I even get on paper!

Seven random things about me:

- At the age of 41, I am to become a father for the first time!

- I grew up in Wool

- I carry the ΔF508 variant of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene

- In 1986 I was at the top of the score table for Spindizzy in Computer & Video Games magazine

- I have no middle name

- For a few years I was a fellow of Pembroke College, Cambridge.

- I think Jerusalem Artichokes should be classified as “poisonous”.

And so I pass on to the next members of the chain, who should feel under absolutely no obligation to do anything about this at all!

*More properly Professor Dame Athene Donald, FRS who led the group I worked in at the Cavendish Laboratory.

Jan 18 2012

Strike 2!

I’m on strike again today, as I was at the beginning of December when I took the opportunity to write quite generally about the role of trade unions (here).

I’m on strike again today, as I was at the beginning of December when I took the opportunity to write quite generally about the role of trade unions (here).

This time I thought I would write a bit more specifically about why I am on strike.

I joined Unilever in 2004, at the same time joining the final salary pension scheme – I have a leaflet in front of me now explaining the “excellent benefits”. In 2007 the company announced it was closing the final salary scheme to new employees but it said that existing members could remain in the scheme, paying higher contributions to retain their benefits, this is what I have been doing since April 2008, when the changes took effect.

In April 2011 the company announced that it was intending to close the final salary scheme to current members, announcing the start of a statutory “consultation” process.

I’m one of those at the softer end of the impacts: I stand to lose 13% of my pension, prior to the consultation I stood to lose 20%. This is because my already accrued benefits will be eroded by a cap as well as the new career average scheme being less generous than the current scheme, my longer serving colleagues (of which there are many), stand to lose more.

To use an analogy: if you offer to cut my leg off but on consultation decide to only do so below the knee then you’ll find I’m not particularly impressed and explaining that you had “improved” your offer is frankly insulting.

It turns out there are specialist “Pensions Communications” companies, Unilever is using Andrew Hodges Consulting. I’m not sure if it was their idea for Unilever to use jolly little cartoons in the post-consultation communications – but it has been the most effective recruiting sergeant for the strike action!

Much has been made by Unilever of the unions “walking out” of the negotiations – this is a rather partial presentation: the unions left because the company refused to discuss any means by which the final salary scheme could be retained and would not discuss the pre-existing career average scheme in isolation with the unions.

It isn’t as if Unilever is doing badly in terms of profits and executive pay, and even the pension fund is in a pretty healthy state: as of March 2011 the scheme was 91% funded, rising from 89% in March 2010 and 69% in March 2009 – it was effected by the recession but was recovering well. With the career average scheme already in place for new employees, the liabilities of the scheme would have been reduced over the coming years. Contrary to the impression companies might give life expectancy is not improving in great leaps and bounds, it is steadily increasing in a predictable manner and has been for many years.

The company has made much of a “no-fly zone”, an offer to make no further changes for a period of a 2 or 3 years. I don’t expect to draw my pension for another 25 years or so – therefore I can anticipate a good few more changes before I retire. My view is that the company intends to have us on a defined contributions before too long. It highlights the problem with pension schemes in the private sector: how many companies can look forward for the 60 years that a pension requires?

Until recently I was proud to be an employee of Unilever, a company that led the way in looking after its workforce as well as its consumers; a company whose vision for the future was to double the size of the business without increasing the size of its environmental impact.

Today I am no longer proud to work for Unilever.