Author's posts

Sep 14 2011

Get Organised!

This is a post about how I record my research, I write it in the hope that others will reveal some of themselves and perhaps gain something from the writing. I write it because how exactly people work is something of a mystery.

This seems like something I’ve picked up slowly over many years rather than being taught it all in one big bang as an undergraduate. I suspect there may have been attempts to teach me this, but sometimes it takes getting it horribly wrong for you to learn stuff, like the importance of backing up your files.

Clearly scientific literature (including company internal reports) has always been important to my work. I wrote a little bit about scientific publication a while back (here). Generation 1 of my filing system was Windows 3.1’s Cardfile program which I used at the start of my PhD, for each paper I photocopied I typed the details onto an index card. I wrote a sequence number on the corner of each printed paper along with a couple of keywords which I also enter into whatever indexing system I’m using and filed it away in a filing cabinet, ordered by the sequence number. These days most papers are available as PDF and I file this in a directory with the sequence as the first part of the filename.

After Cardfile I moved on to Endnote, and currently I use Reference Manager which are more specialist pieces of software specifically designed for storing the details of publications and also formatting bibliographies in popular wordprocessing packages. Notes on the contents of a paper still get scribbled onto the paper copy in red ink…

These days Zotero and Mendeley both look like good free options for reference management. I haven’t switched to Zotero because it’s currently tied to the Firefox browser and I haven’t switched to Mendeley because I’m not absolutely certain what it is syncing to the Cloud and what other people can see of it there, exposing even the titles of internal company reports to outsiders is a Very Bad Thing. I also had some minor problems importing my legacy collection into Mendeley. Unlike previous iterations of such software Zotero and Mendeley both make reasonable attempts at extracting paper details from PDF files or webpages.

Stray bits of paper scribbled on at meetings I still haven’t really cracked, I try to write the date and a sequence number on any bit of paper I use, and some link to the project it relates too but this is unsatisfying. For many years I’ve considered scanning in bits of paper; our company photocopiers will e-mail scans of paper to you in PDF format and with harddisk space being so cheap now* it seems odd not to do this. All this means I still have a folder per project where bits of paper end up. And, truth be told, I still find it easier to comment on a bit of work by scribbling on a bit of paper.

I’ve started using OneNote a bit for odd note collecting, the OneNote metaphor is of a collection of notebooks, each notebook is divided into sections by tabs along the top of the page and each section is divided further into pages using tabs down the righthand side of the page. My main problem with OneNote is that it’s not possible to display your notes in date order, I seem to use it mainly for a jumping off point to other things.

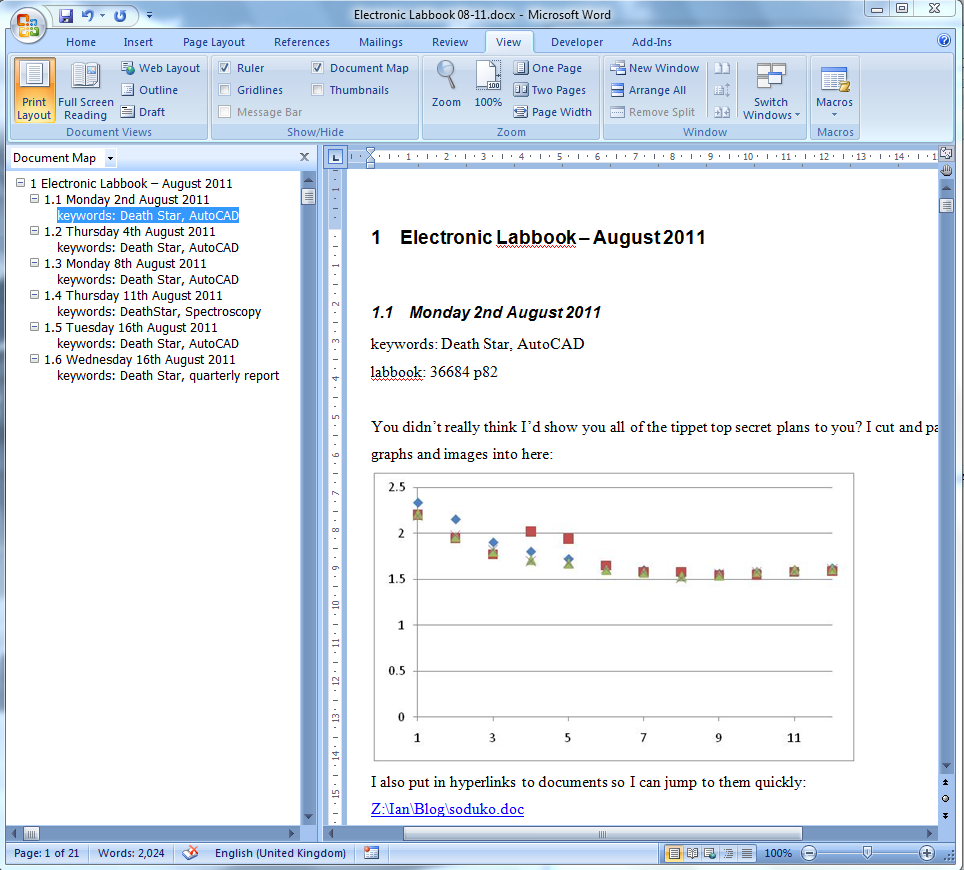

My lab books have been the core of my research since I started my PhD., in my loft there’s a sequence of about 20 of them. Some of my colleagues have fantastically neat lab books with diagrams and graphs carefully sellotaped in and orderly paragraphs describing the experiments done, I never really got that well organised but I did a fair job of adding to an index at the front of each one. I still use paper lab books today but at a reduced rate. I’ve switched to a system using Microsoft Word, for each month I have have a document which looks like the one below:

I can type things in, hyperlink to other documents and cut and paste graphs and pictures as well. I use the Document Map view and, by applying appropriate styling, I get quick links to each day with a view of the keywords for the day – in this instance, designing the Death Star in AutoCAD ;-) For each year I get 12 documents which I store in a folder for that year. The thing I haven’t got working in this system is nice keyword searching across multiple years.

I’ve worked on multiple projects throughout my career and I’ve come to the conclusion that trying to separate them for the purposes of lab books and references doesn’t work too well – you end up spending time working out which lab book / file you should be adding stuff to and with decent indexing it just isn’t necessary.

These days you can buy specialised electronic lab book software, it seems it is normally done at a large scale though rather than by individual which I can’t help thinking is not a good thing since we all have individual ways of working which will vary with both the work we do and our own personal ways of doing things.

Looking at my current electronic lab book it strikes me that WordPress could be used for the task. The thing that Word can’t do easily is to give me rapid links by category or date to any part of my labbook but it strikes me that WordPress does this pretty well if you put the appropriate widgets into the sidebar. I suspect any electronic lab book software is essentially a database with a front end, for WordPress the front-end is written in PHP. The benefit of WordPress is that it’s very widely used, with lots of plugins to provide new functionality and extending it is within the reach of most programmers.

Here endeth the world’s dullest blog post, comments on your own “ways of working” are most welcome!

*Except if you’re in a corporate environment, in which case the laws of every decreasing disk space cost seem to work differently.

Sep 10 2011

Don’t call me scum*

Scum. Goodbye NHS. Goodbye Lib Dems. RT

@skynewsbreak: MPs vote in favour of NHS reforms by a majority of 65

This was retweeted on timeline by a number of people on twitter on Wednesday last. As a Liberal Democrat this upsets me, I take it personally. According to Ben Goldacre, Evan Harris is okay, “good scum” presumably – the rest of us have obtained no exemption.

At roughly the same time my twitter feed was full of people decrying Ken Clarke for describing the rioters as a “feral underclass”, not so many were bothered about me being referred to as scum. Clarke had a point but he made it poorly. His point was that what we should be concerned that 75% of the rioters were already known to the police, our justice system had failed to rehabilitate them. It’s a useful example though: if you use language which offends you’ll find people will ignore your argument, assuming you simply don’t have one.

Interestingly Tony Blair was on the radio this morning, a man that lied in order to take us into war in Iraq and stood by as the country disintegrated, unwilling to persuade the US of the critical need for a post-war recovery plan. People on my timeline were upset but no one called him scum.

*It’s a reference to that fine film, Barb Wire.

Sep 10 2011

Medical ultrasound imaging

Alert readers will remember that I am in the process of becoming a father, and that the occasion of this announcement was the "dating scan" (Codename Beetle). In the UK, at least, this is an ultrasound scan targeted to take place at about 12 weeks pregnancy with a view to getting a more precise estimate of birth date from the size of the fetus, measured from “crown” to “rump”. Alongside this a nuchal fold measurement may be made to help test for Down’s Syndrome, it turns out this requires a cooperative fetus willing to assume just the right posture, Beetle wasn’t!

Alert readers will remember that I am in the process of becoming a father, and that the occasion of this announcement was the "dating scan" (Codename Beetle). In the UK, at least, this is an ultrasound scan targeted to take place at about 12 weeks pregnancy with a view to getting a more precise estimate of birth date from the size of the fetus, measured from “crown” to “rump”. Alongside this a nuchal fold measurement may be made to help test for Down’s Syndrome, it turns out this requires a cooperative fetus willing to assume just the right posture, Beetle wasn’t!

From a scientific point of view this is all really interesting: you can see inside people! In this instance, my wife.

The inside of a human is largely squidgy but different parts have different squidginess, in particular there is a nice contrast between the muscular wall of the womb and the liquid contents and again between the liquid contents of the womb and the fetus. Ultrasound is reflected when there are interfaces between things of different squidginess. There’s a direct analogy between this squidginess and the “impedance” of electrical components in things like hifi equipment, and the transmission of sound waves and the transmission of radio waves.

The scan starts off with the operator squirting generous quantities of lubricant onto the wife’s belly (in a hospital environment this gives me flashbacks to the Unexpected Prostate Examination Incident). The lubricant is to give good “impedance matching” between the ultrasound scanner and the swollen belly of the wife, without it the sound bouncing off the skin surface would be all you heard.

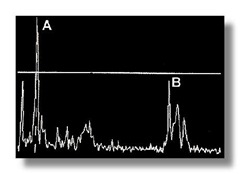

To build up an ultrasound image we listen for echoes. The ultrasound probe lets out a squeak and waits for echoes, the time taken for the echo to arrive tells you how far away the thing that created the echo. This is really obvious in the earliest ultrasound devices which worked in what is know as “A-mode”: sending out a single beam of sound in one direction and recording the sound that came back as a function of time. Typical data* shown below.

The echo marked A represents a structure closer to the surface than the echo marked B.

You can build up a proper image by scanning your beam of sound backwards and forwards to map out a fan, this is known as “B-mode” and is the type of imaging you will be most familiar with, the image at the top of the page is an example. It shows a vertical fan-shaped slice into the body, with features at the bottom of the scan further from the surface than those at the top.

In the old days moving the beam backwards and forwards was a mechanical process but modern scanners do it electronically with no moving parts. This is done with a “phased array” similar to those used in radar systems; a line of transmitters is fed signals with different phases (the sinusoidal sound waves are offset in time by different amounts) the result of this is a sound beam that can be steered backwards and forwards without physically moving any parts.

These days you can even get “4D” scans done. These use a square (2D) array of emitters to scan rapidly over an area, getting the third dimensions from the echo time and a fourth (time) dimension by being able to repeat the process rapidly. These scans are converted to a moving 3D surface (or “baby”) by thresholding the 3D data set and using computer graphics techniques to produce nice graphics. I must admit I find these images a bit creepy (the one on the right is not Beetle). Given my experience of image analysis, extracting a neat surface from the noisy data, in real time, is pretty tricky.

These days you can even get “4D” scans done. These use a square (2D) array of emitters to scan rapidly over an area, getting the third dimensions from the echo time and a fourth (time) dimension by being able to repeat the process rapidly. These scans are converted to a moving 3D surface (or “baby”) by thresholding the 3D data set and using computer graphics techniques to produce nice graphics. I must admit I find these images a bit creepy (the one on the right is not Beetle). Given my experience of image analysis, extracting a neat surface from the noisy data, in real time, is pretty tricky.

If I’d been paying attention I could probably have read the name of the particular ultrasound scanner used on my wife, but I had other things on my mind. As it was I could identify it because there’s an interesting looking coding on the sonograph (RAB-4-8L/0B) which turns out to be the serial number of a detector for the General Electric Voluson 730 devices. A quick bit of googling reveals a convincing looking image of the scanner, they cost something in the range £20k-£40k.

If I’d been paying attention I could probably have read the name of the particular ultrasound scanner used on my wife, but I had other things on my mind. As it was I could identify it because there’s an interesting looking coding on the sonograph (RAB-4-8L/0B) which turns out to be the serial number of a detector for the General Electric Voluson 730 devices. A quick bit of googling reveals a convincing looking image of the scanner, they cost something in the range £20k-£40k.

Ultrasound imaging utilises sound in the frequency range 2-18MHz although for the probe used for Mrs S’s scan the range is 4-8MHz wavelengths for such waves are 0.2-0.3mm which will be the maximum achievable spatial resolution. The lowest of these ultrasound frequencies is 100 times higher than the upper limit of human hearing at 20kHz, and 10 times higher than those used by bats and dolphins.

The velocity of sound waves in water is 1540m/s, for the purposes of this calculation humans are approximately water, the raster rate (speed at which the sound beam goes backwards and forwards) appears to have been 18Hz or once every 1/18th of a second). Given the speed of sound in Mrs S, we could actually image many metres into her – if required. This suggests that the speed sound is not a limiting factor in how fast we can do scans: the noise in the signal is the limiting factor. That’s to say the strength of the echoes we get back is rather weak and looking at the images they are mixed with a lot of noise.

Ultrasound machines are really rather high technology bits of kit, containing lots of interesting physics. I must admit having read up a bit – I want one to play with!

*”Typical data”, in scientific terms means “I’m going to claim this is typical but actually this is the best we collected”.

Sep 03 2011

Book review: The Lunar Men by Jenny Uglow

I read “The Lunar Men” by Jenny Uglow a few years ago, this was in a time before blogging so I’d forgotten the contents. I’ve recently reread it, my interest reawakened by my recent reading of the King-Hele biography of Erasmus Darwin. Darwin was a key member of the group of industrialists, inventors, doctors and experimenters based in the West Midlands which finally became the Lunar Society.

I read “The Lunar Men” by Jenny Uglow a few years ago, this was in a time before blogging so I’d forgotten the contents. I’ve recently reread it, my interest reawakened by my recent reading of the King-Hele biography of Erasmus Darwin. Darwin was a key member of the group of industrialists, inventors, doctors and experimenters based in the West Midlands which finally became the Lunar Society.

Uglow lists the principal Lunar men as John Whitehurst (1713-1788), Matthew Boulton (1728-1809), Josiah Wedgewood (1730-1795), Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802), Joseph Priestley (1733-1804), William Small (1734-1775), James Keir (1735-1820), James Watt (1736-1819), William Withering (1741-1799), Richard Lovell Edgeworth (1744-1817), Thomas Day (1748-1789), Samuel Galton (1753-1789).

It’s notable how many of the Lunar Men were Scots, in the mid-18th century England had two universities, Scotland had five.

It’s not until 1775 some 15 or so years after the core group had originally met that the Lunar Society is formalised. At the time arranging events to coincide with the full moon was not uncommon. Alongside the Royal Society there were numerous other local “Philosophical Societies” although I’m not clear of the details of these other groups it seems there was nothing exceptional about the Lunar Society in terms of the mix of people but they were rather exceptional people. They were proactive in seeking out new members, for example Withering was recruited on the death of William Small. As gradually the founding members died, the group dissolved in 1813.

Matthew Boulton, owner with John Fothergill of the Soho Manufactory, started as a maker of “toys” (which in this case means any number of small metal items) and non-ceramic ornaments but he collaborated with James Watt to make stream engines. He was later to set up the Soho Mint, which used patented pressing equipment to make high quality coins and medals in bulk.

James Watt made his first breakthrough in the design of steam engines in 1765 but it wasn’t until 1775 that they received a 25 year extension of the key patent and in 1776 they install their first engine in Cornwall. The revenue from these engines came in the form of a fee related to the cost savings on coal which the more efficient design of the Watt engine provided compared to the Newcomen atmospheric engines, introduced in the early 1700s. The protection and creation of patents was an important part of the Watt and Boulton business plan, they even supported Richard Arkwright, with whom they did not see eye to eye, in the protection of his patents for the cotton processing equipment at the heart of his factory. Patents are one route to deriving income from intellectual property, the newly formed Society of Arts offered another route: prizes, or premiums, for named topics which centred around manufacture.

On the face of it the presence of Josiah Wedgewood, a potter, in the group seems odd but reading the book it becomes obvious just how high-tech an industry the potteries were. Clay is not simply dug up from any old patch of ground and flung on a wheel – the correct raw materials must be selected and once this is done they must be processed properly before they can be formed into shapes. Even then it isn’t over: the process of applying glazes and firing the ceramics is far from straightforward. The ceramic industry was one of the high tech industries of its time, an 18th century Silicon Valley.

Boulton and Wedgewood were both in the business of mass producing desirable consumer goods and marketing them to the middle classes. They recruited excellent artists to produce designs, often based on classical themes and objects. Initially selling them to the very wealthy but with a view to mass production and the use of their aristocratic clients as promotional material. For Wedgwood the culmination of this was the creation of replicas of the Portland Vase.

Alongside the factories growing up in the Midlands came the canals with which the Lunar Men were heavily involved. The canals brought freight costs down from 10d per mile to 1.5d per mile. They started to replace the turnpike roads and river navigations, both enabled by acts of parliament which gave rights to maintain roads and rivers to corporation – along with the right to raise tolls. This previous incarnation of transport seems to have been initiated around 1650. By the mid-19th century a full-scale rail network was in place, replacing in turn the canals. The canals meant that raw materials could be moved around more cheaply, and that expensive (and delicate) manufactured goods could be shipped out.

The Lunar Men had a range of political views, although Uglow comments that scientific experimentation was more associated with Whigs than Tories. The manufacturers, Boulton and Wedgwood, were notably less radical most likely with an eye to maintaining the political support required to keep their businesses running, although Boulton in particular was pretty progressive in the treatment of his workforce. Many of the group were supportive of the French Revolution, American independence and the abolition of slavery. Priestley was a Dissenting preacher, and when the backlash against all manner of radical thought came his house was one of 30 or so properties singled out for attack during the 1791 Birmingham Riots, Withering’s house was also attacked.

The scientific context is quite different compared to today: public demonstrations of cutting edge science including electrical demonstrations were common and a group of educated gentlemen could make valuable contributions to science as amateurs doing the work in their spare time. Withering and Darwin fought over the discovery of digitalis as a well-defined medical material. Priestley was probably the most impactful “scientist” of the group being one of several who played a key role in the discovery of oxygen and it’s properties. Darwin was largely a “scientist” who suffered from having ideas before his time particularly with regard to evolution but also his ideas on meteorology were in advance of his time. Others in the group such as Watt and Keir were clearly entirely competent in scientific areas.

Strangely I found the King-Hele biography of Erasmus Darwin pretty much as informative on the Lunar men as this book and more readable – perhaps because it’s more difficult to write a compelling narrative around a, sometimes loose collective, compared to an individual. I am now intrigued about the evolution of factories in the 18th century and, more disturbingly, 18th century intellectual property rights.

Sep 02 2011

Friday rant

t-mobile get the pointy end of this because they come at the end of a day wherein I was assailed from all sides by idiocy.

18 months ago I became the proud father of Shiny, an HTC Desire phone on a contract for £20 per month, a novel experience for me. Shiny is mainly used as a internet access device rather than a speaky texty phone and I’ve been very happy with it.

So at the end of 18 months I am free of my original contract to t-mobile and can seek something cheaper, the key thing being unlimited* internet access. I look on the t-mobile website: it says they’ll offer me £6 off my contract going forward for a 12 month lock-in or some such. Carphonewarehouse, on the other hand, offers me a £10 per month SIM Only contract with t-mobile on monthly rolling basis, oddly 12 month contracts are £15. This, anyway, is a “no-brainer”, I get a monthly rolling SIM only contract with t-mobile contract for £10 which is less than the t-mobile renewal offer of £14. This requires a conversation with carphonewarehouse’s call centre which sounds a little cramped because I can hear my man Paul’s neighbour demanding a stapler and another having somewhat groundhog-day sounding conversation about “which shop did you get this better offer in?”

Anyway this is sorted, all I need to do is ring up t-mobile once my new SIM card is delivered and get my number transferred from my old account to my new one. Apparently this requires t-mobile to provide my PAC number to themselves (don’t ask me!).

Fail one is that on ringing the t-mobile 150 service I get a list of numeric options: I need option 2 but the service doesn’t recognise my many and creative ways of pressing the 2 key on my keypad. Actually it’s a softkey rather than an actual real key but it had 2 written on it so I pressed it.

By pressing 1 I get through to an actual person who establishes that I need transferring to their cancellation department – you see I currently have two contracts with t-mobile and I want to cancel the old one and transfer the number to the new one, as an interesting aside the chap at carphonewarehouse told me my credit rating is so good I can have 4 contracts! The person I’m talking to has a pleasant Irish accent although I can’t help thinking she is actually an Indian who has been trained to speak with an Irish accent to reassure me#.

After waiting on hold for a few minutes I get another person this time with a pleasant Welsh accent (proviso as above), anyway she tells me I “can’t” transfer my phone number from one t-mobile account to another. Now I’m a bit hardline on these things: I can transfer a number from a non-t-mobile account to a t-mobile account by invocation of the PAC number therefore logically I “can” do the described transfer therefore “can’t” actually means “won’t”. However, it turns out that I can convert my existing contract to a £5 per month contract equivalent to my new SIM only contract but with a 24 month contract period. Needless to say this was not visible on any website. We agree to do this.

So at the end of two rather complex phone calls I have reduced my phone bill from £20 per month to £5 per month (actually £6 with VAT). I do have a PhD, and whilst this may not endow me with great nouse, it does mean I’m not a dribbling idiot – yet to me this process has been ridiculously Byzantine and complex. It’s taken me two 20 minute phone calls to do what should be a couple of button presses.

I do feel sorry for the poor souls that inhabit these call centres because I’m actually a polite sort of chap but the wrangling I have to engage in does make even me a bit tetchy and they, through no fault of their own, get the pointy end of that.

Addendum

Wednesday and I’ve just had a chat with t-mobile again, because my online account info doesn’t match what I agreed on the phone on Friday, currently it indicates that my contract is for £8.51 per month exc VAT and that I don’t have the farcically named “unlimited” internet access I signed up for. They assure me that when I get my next bill it will be for £5 plus VAT and the required “unlimited”.

The problem here is that they’ve sent me several messages telling me how great their online account info system is, meaning I’ve gone off and looked at it. What they’re actually trying to do is hide how little they’re willing to charge me for a mobile phone contract. This is all explained nicely in Tim Harford’s book “The Undercover Economist“, the trick is to find out the maximum someone is willing to pay for a service and offer it to them, without prejudicing your efforts with other customers who have a higher maximum price. Price transparency would spoil this game.

Footnotes

*for values of internet access which are limited; actually how do they get away with describing limited internet access as “”unlimited”?

#Personally I don’t care that the call centre might be in India but I am offended that they feel the need to fake an accent to “reassure” me. It’s quite possible that t-mobile’s call centres are actually in England and I have maligned an Irish lady and a Welsh lady.