This is less of a book review and more some notes on music theory as it applies to the guitar. It is based on Music Theory: Everything you ever wanted to know but were afraid to ask by Tom Kolb from the Hal Leonard Guitar Method series.

This is less of a book review and more some notes on music theory as it applies to the guitar. It is based on Music Theory: Everything you ever wanted to know but were afraid to ask by Tom Kolb from the Hal Leonard Guitar Method series.

I’ve been playing guitar for a couple of years, and I found myself increasing asking why I am doing things and how are songs constructed. What notes belong with which chords?

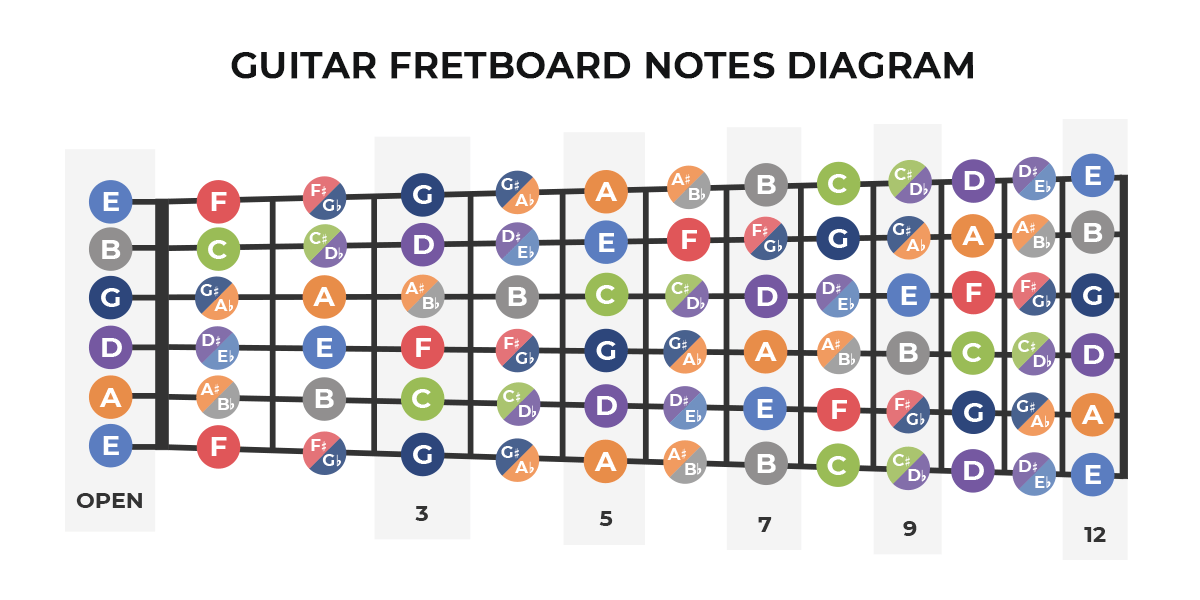

The book starts with a tour of the fretboard, the version below is from the Youcisian website, I use Youcisian app for learning guitar – it’s great.

Kolb recommends learning the fretboard by picking a note and playing it up and down the fretboard at all locations. I have a new toy to help with this – a Polytune 3 tuner pedal!

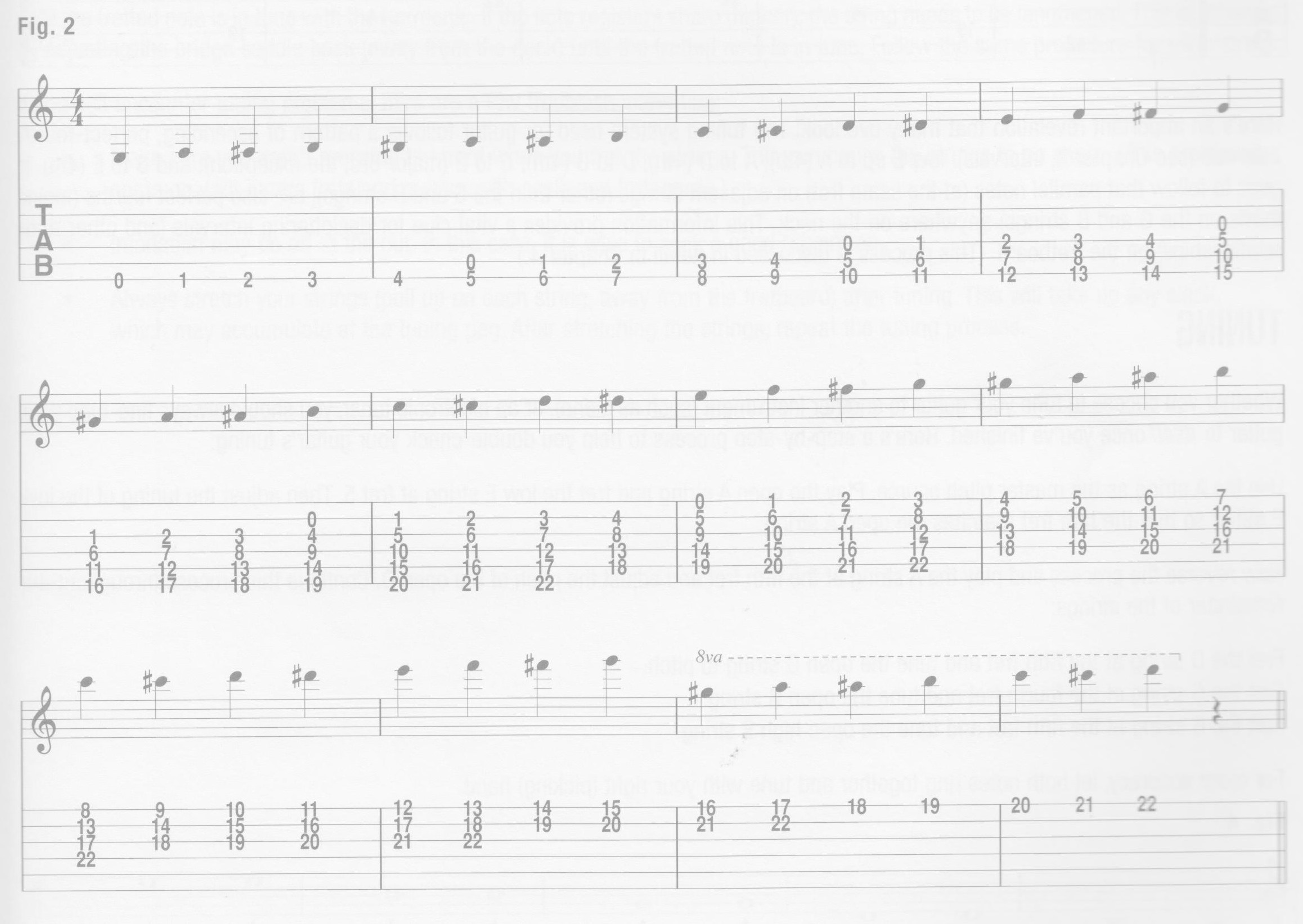

I particularly liked the figure showing how notes on the traditional stave matched up to locations in guitar tab notation.

P5 Figure 2 – how notes are repeated in traditional music notation and tabs

The observation that that the 5th fret on one string is the same note as the open note on the next string, except G to B when it is the fourth fret. This allows you to tune a guitar to itself, It seems like a useful cross-check. There was also a section on tuning using harmonics. I sort of got this working on my acoustic, I found I needed to watch a video: Justin Guitar – How to Tune Your Guitar using Harmonics to understand what I was trying to achieve.

The second chapter is on traditional musical notation, I feel I should know this but it isn’t a priority.

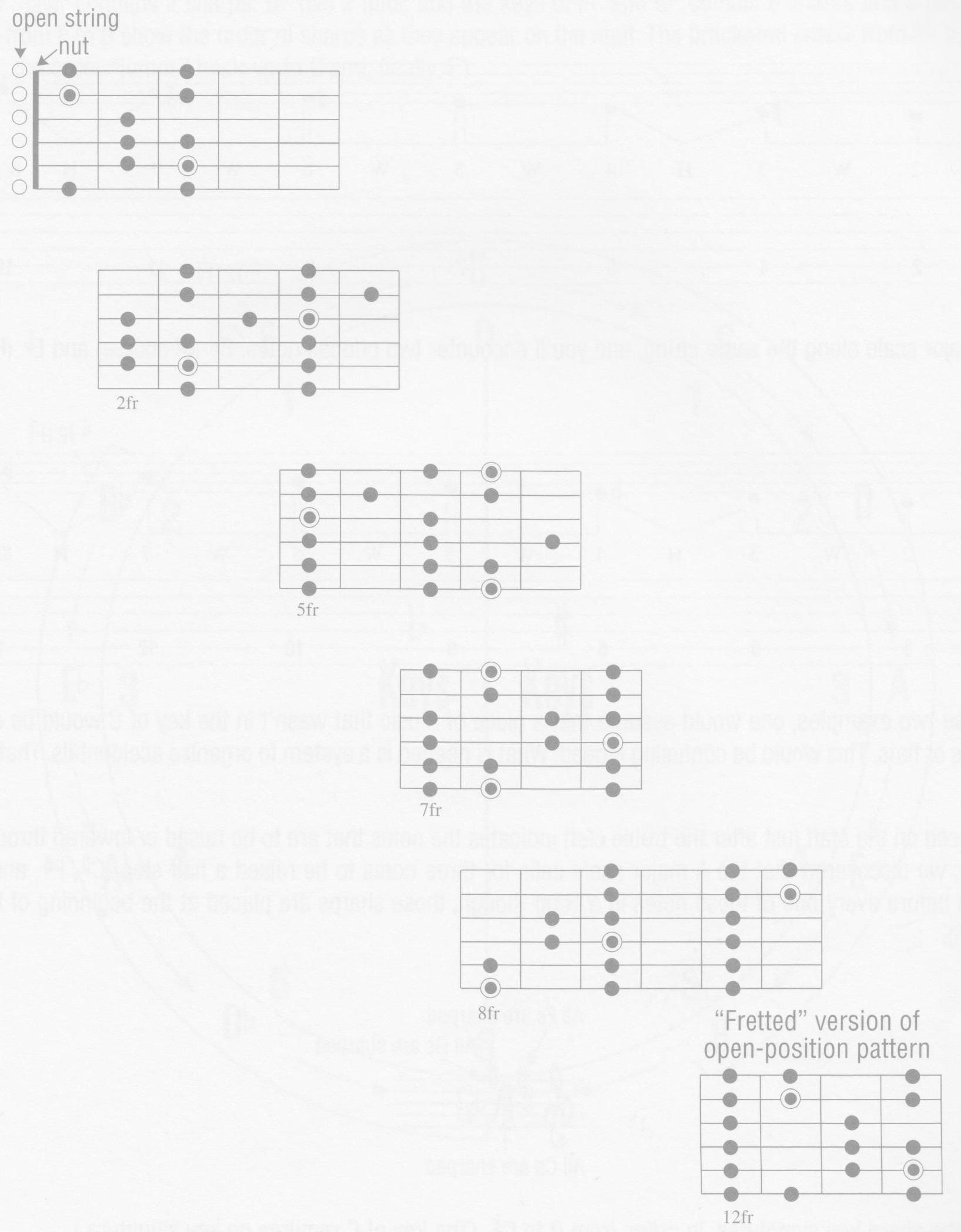

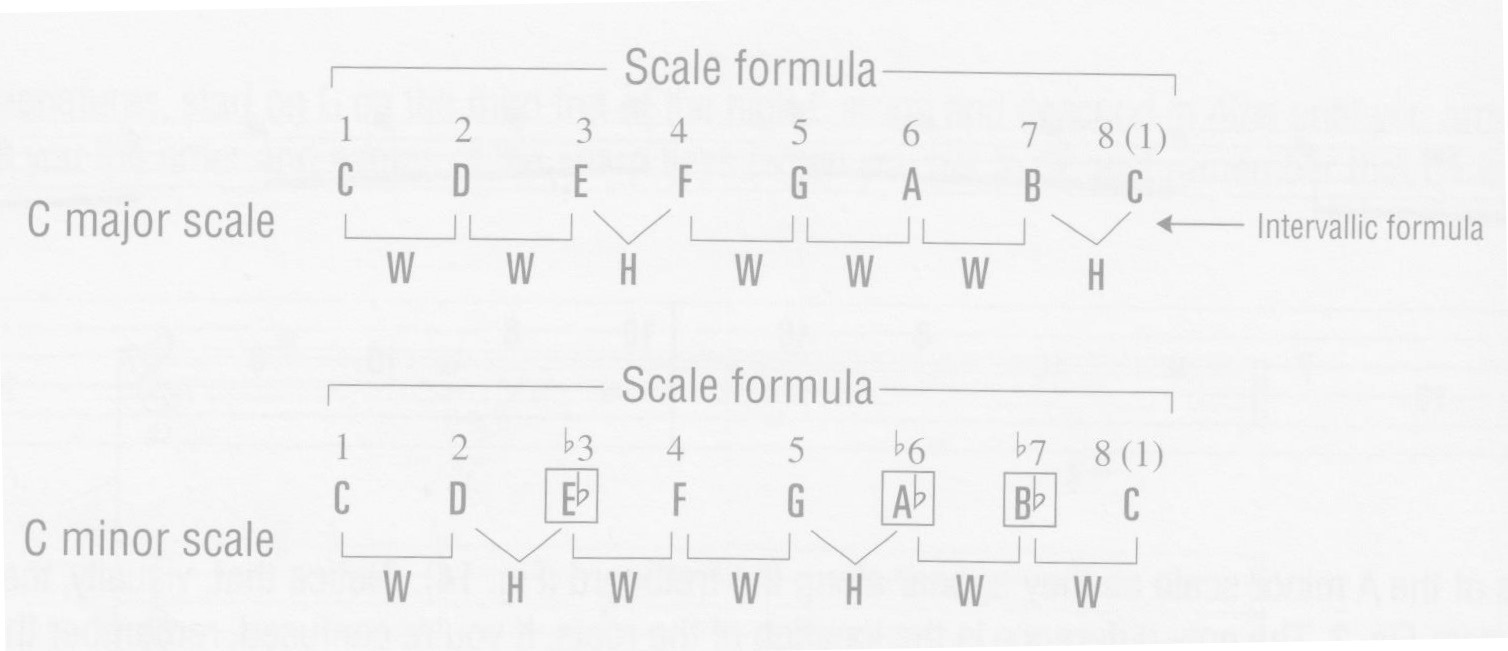

Chapter 3 is about scales and key signatures, there is an algorithm for generating the notes in a major scale. Figure 3 on p17 shows the C major scale in 5 locations on the fretboard.

Page 17 – figure 3 the C Major Scale at different locations on the fretboard

There is similar expression to generate minor scales.

Page 22 Figure 15 shows how the scale formula for major and minor scales compare.

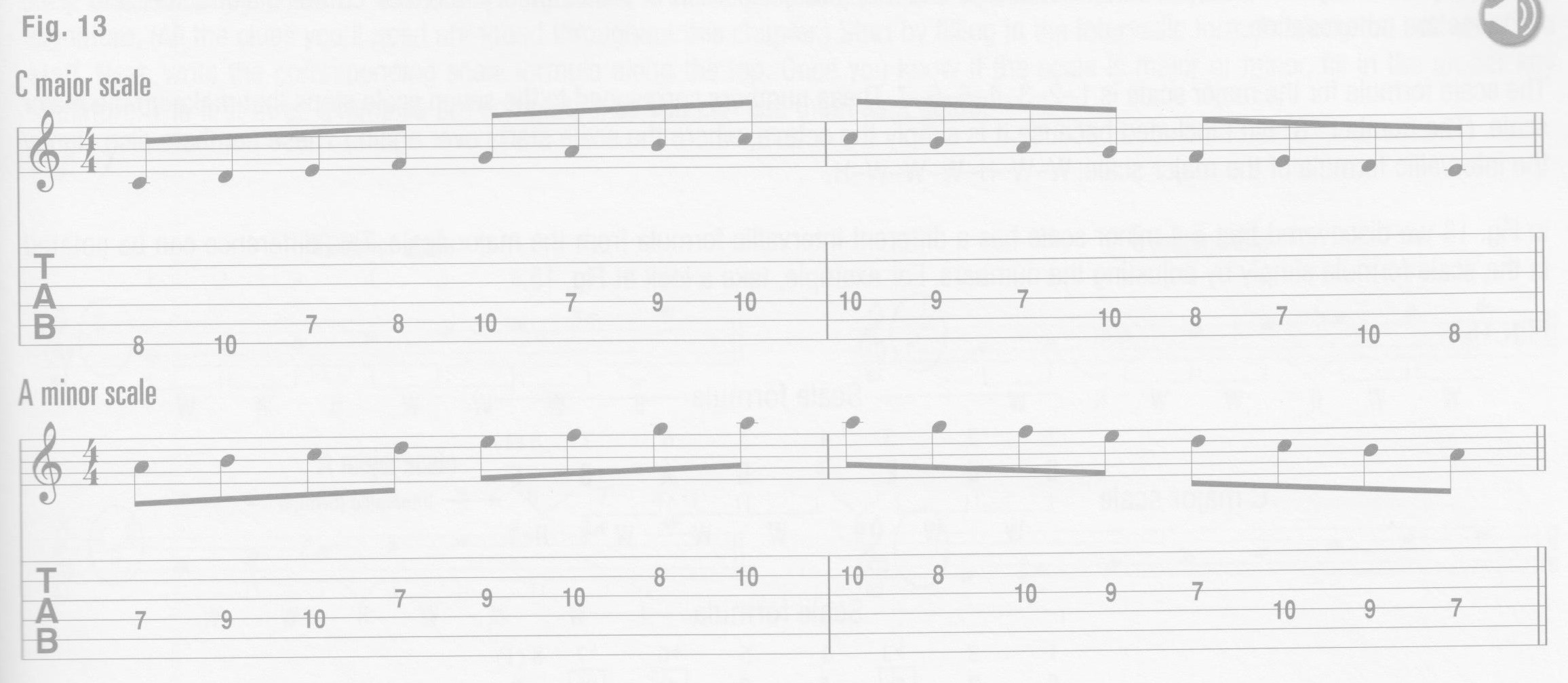

Figure 13 (p21) shows how the C major and A minor scale compare

P21 figure 13 the C major and A minor scales compared

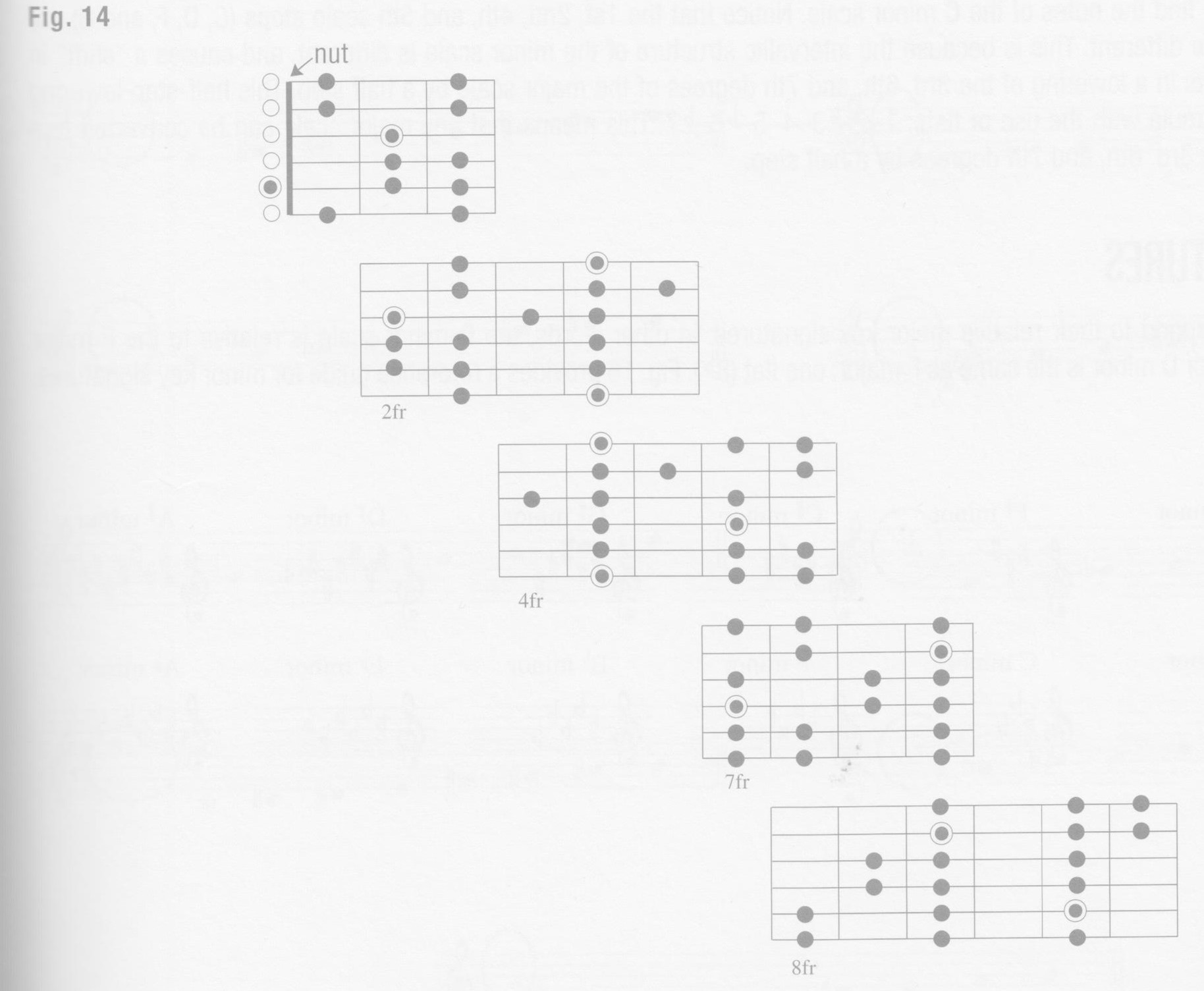

P21 figure 14 the A minor scale at different locations on the fretboard

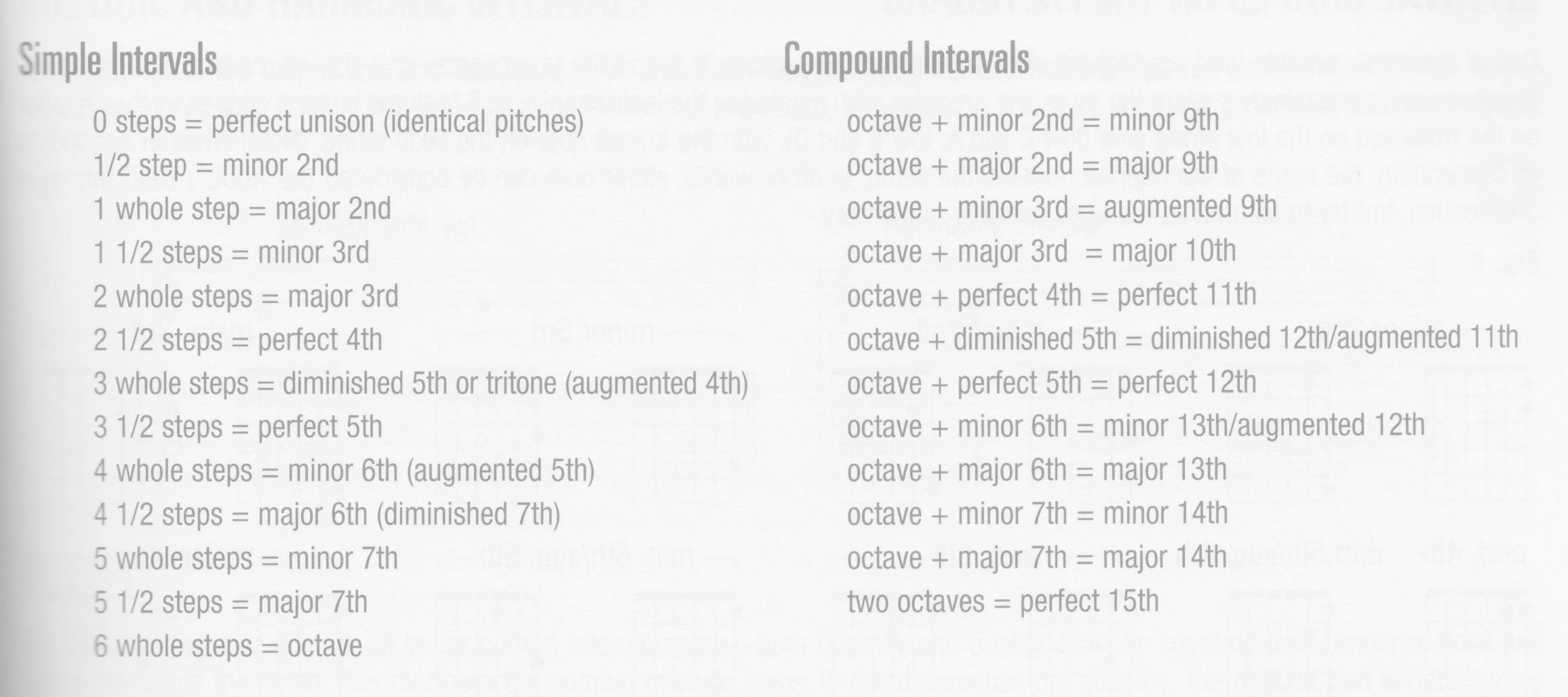

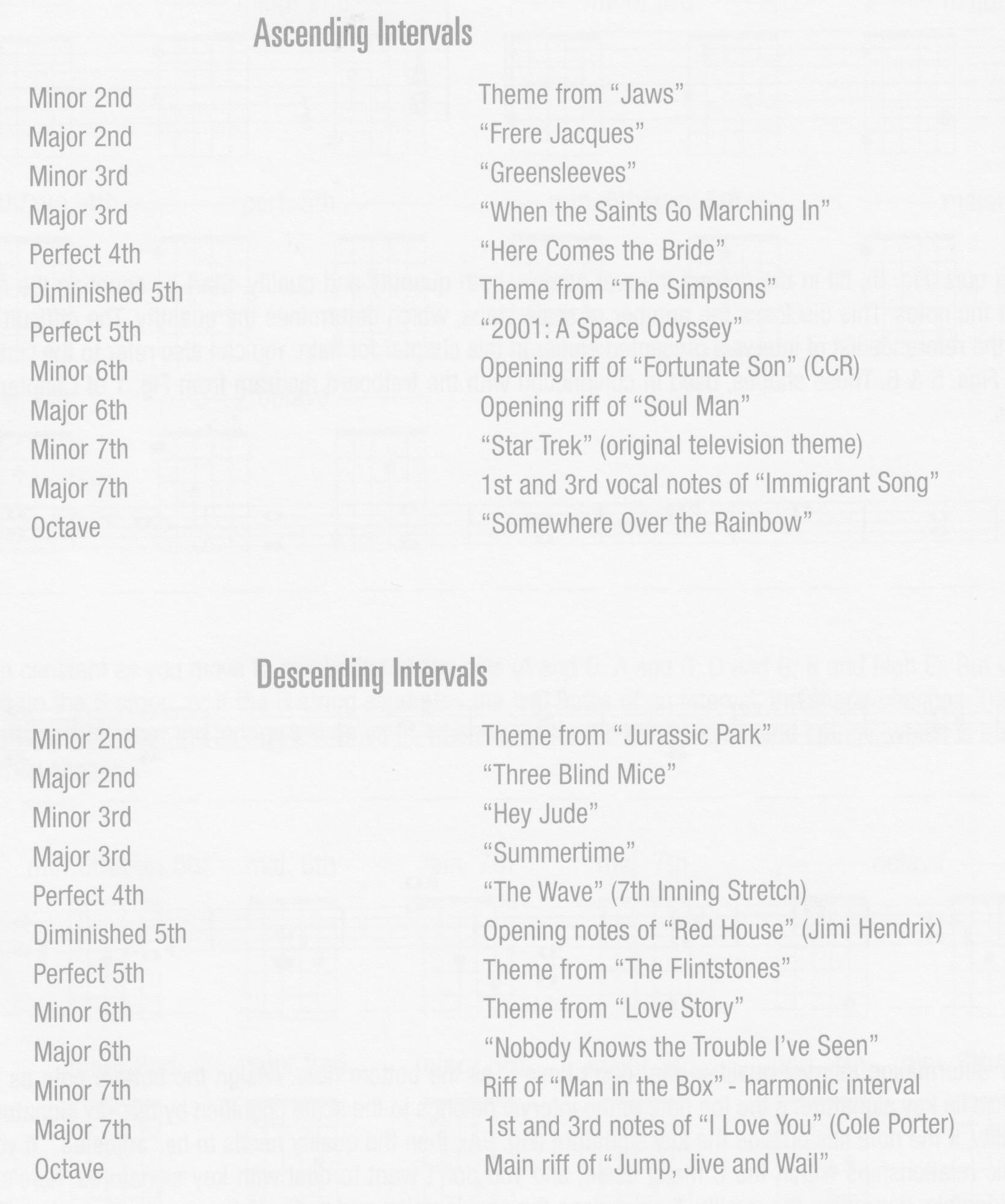

Chapter 4 talks about intervals (steps between notes) and their names. The names of the intervals are listed.

P25 table of interval names

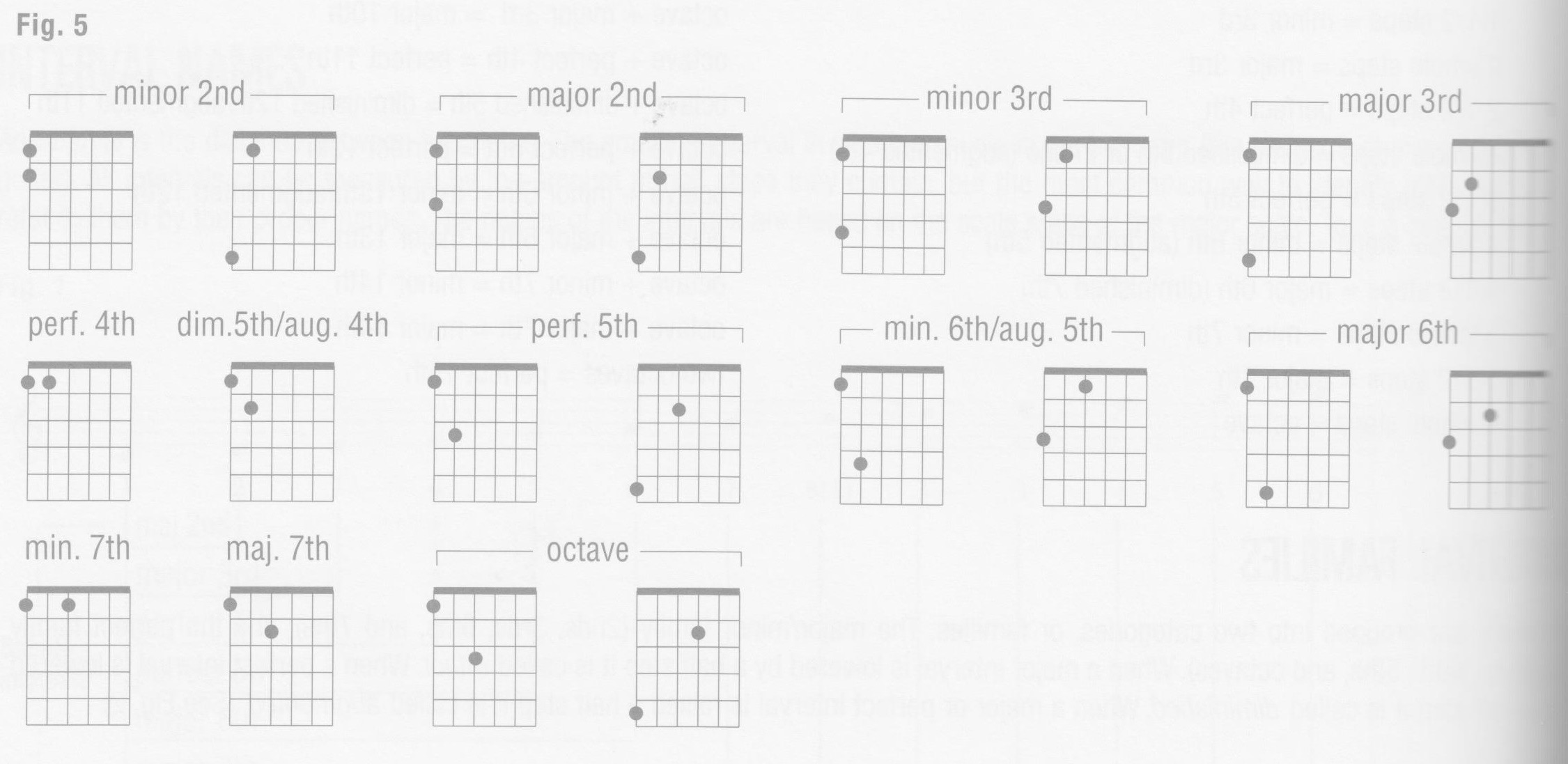

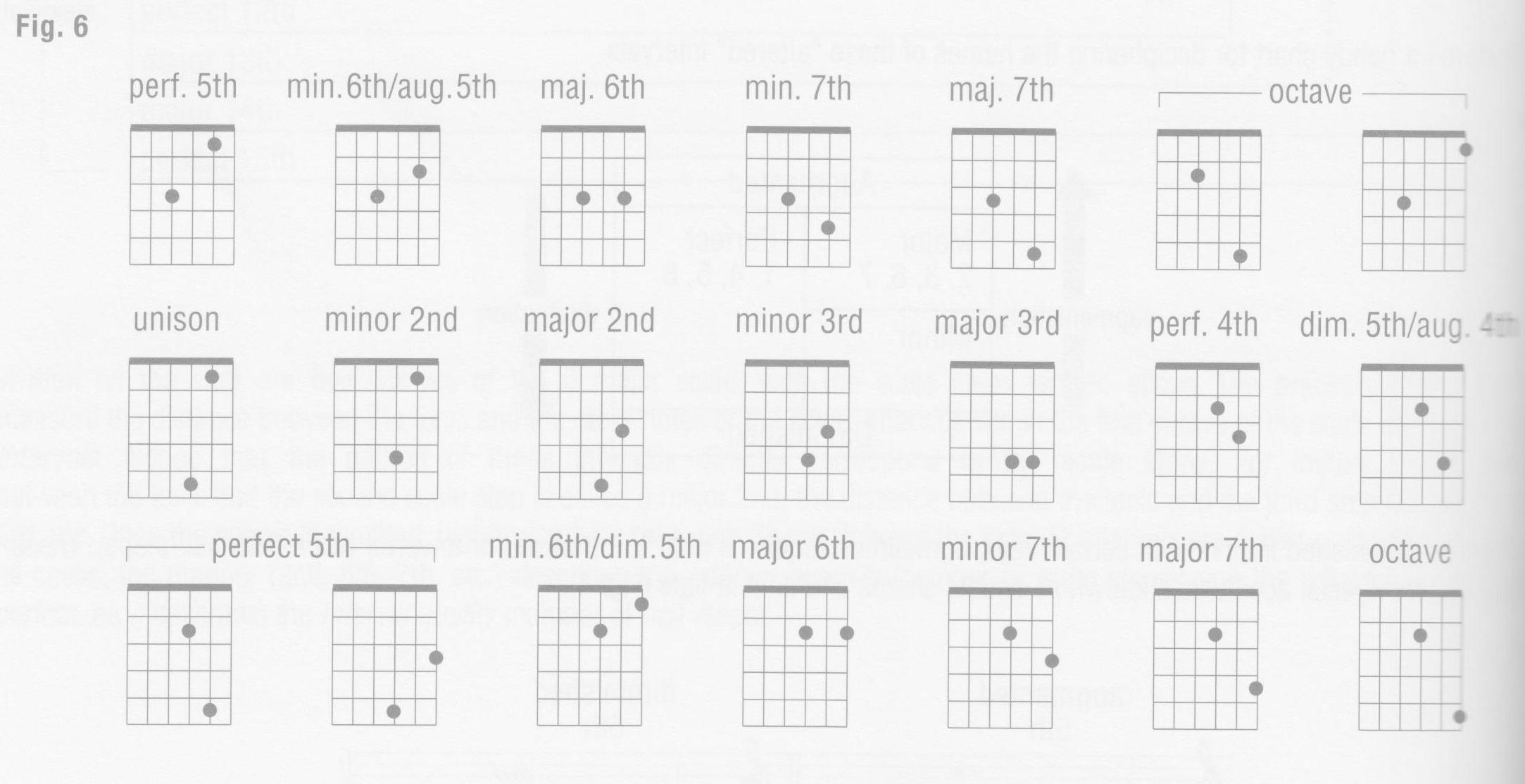

Each fret on the guitar corresponds to 1/2 a step. The different intervals form different patterns on the fretboard, these patterns are moveable but they change around the G-string because the interval to the G-string is four steps rather than 5.

P26 figure 5 interval shapes on the top strings

P26 figure 6 interval shapes on the bottom strings

P28 A list of popular songs illustrating the intervals

Chapter 5 introduces us to triads which form the basis of chords. The pattern for major triads is 1-3-5 and that for minor triads is 1-flat 3-5. Augmented triads are 1-3-sharp 5 and diminished triads are 1- flat 3 – flat 5

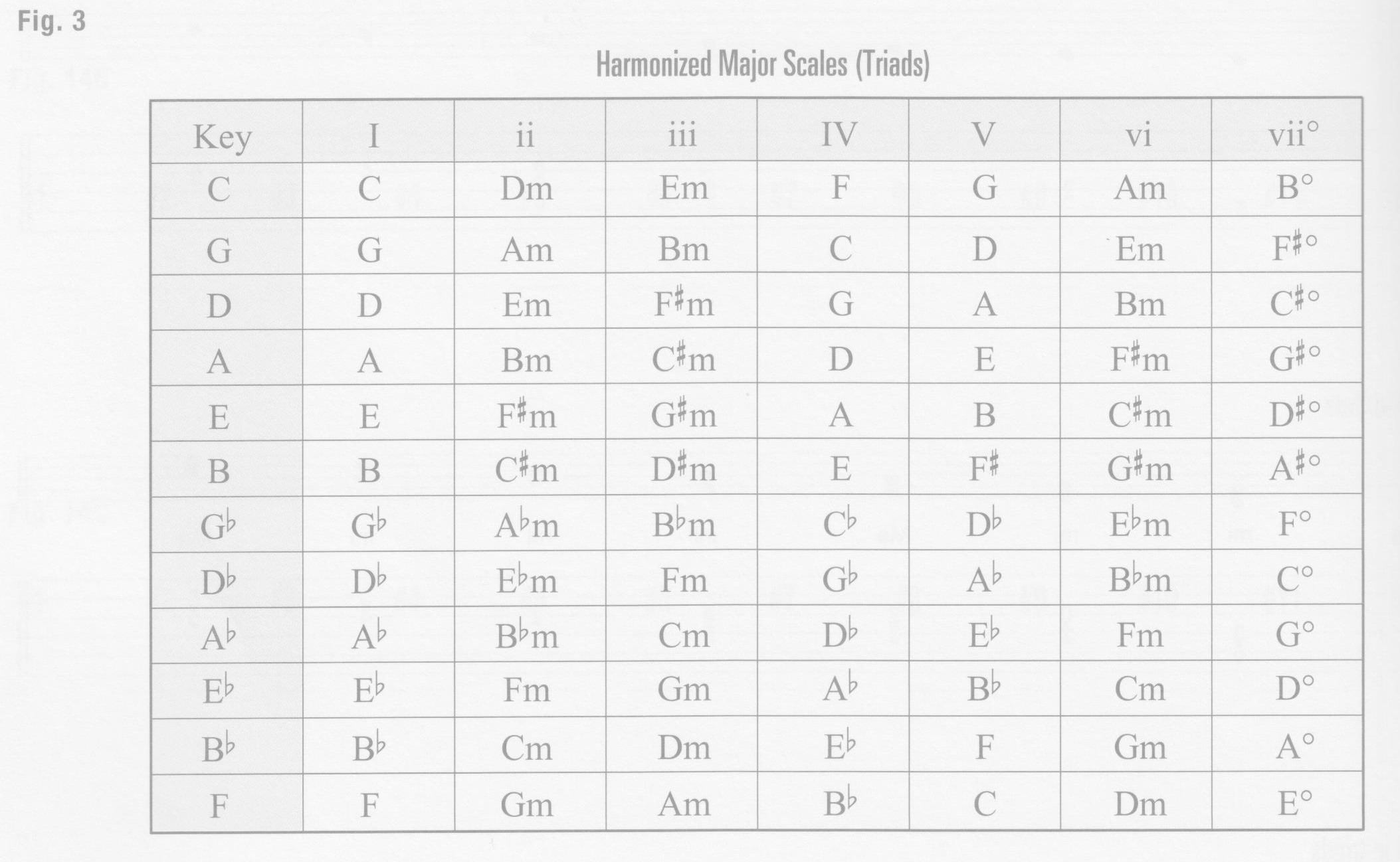

Chapter 6 – harmonizing the major scale chords are related to scales via the process of harmonisation. The chords of a scale are given Roman numerals with the case indicating whether they are major or minor chords, and a o superscript indicating the diminished vii chord. The chords for the major scales are shown in the figure below

P36 Figure 3 Harmonized major scales

Jazz, blues and other music styles use 7th chords which add a seventh to the 1-3-5 pattern. This produces a harmonized chord table which looks like the above but with a 7 added to each chord! Actually the I and IV chords get a maj7 and the V chords just a 7.

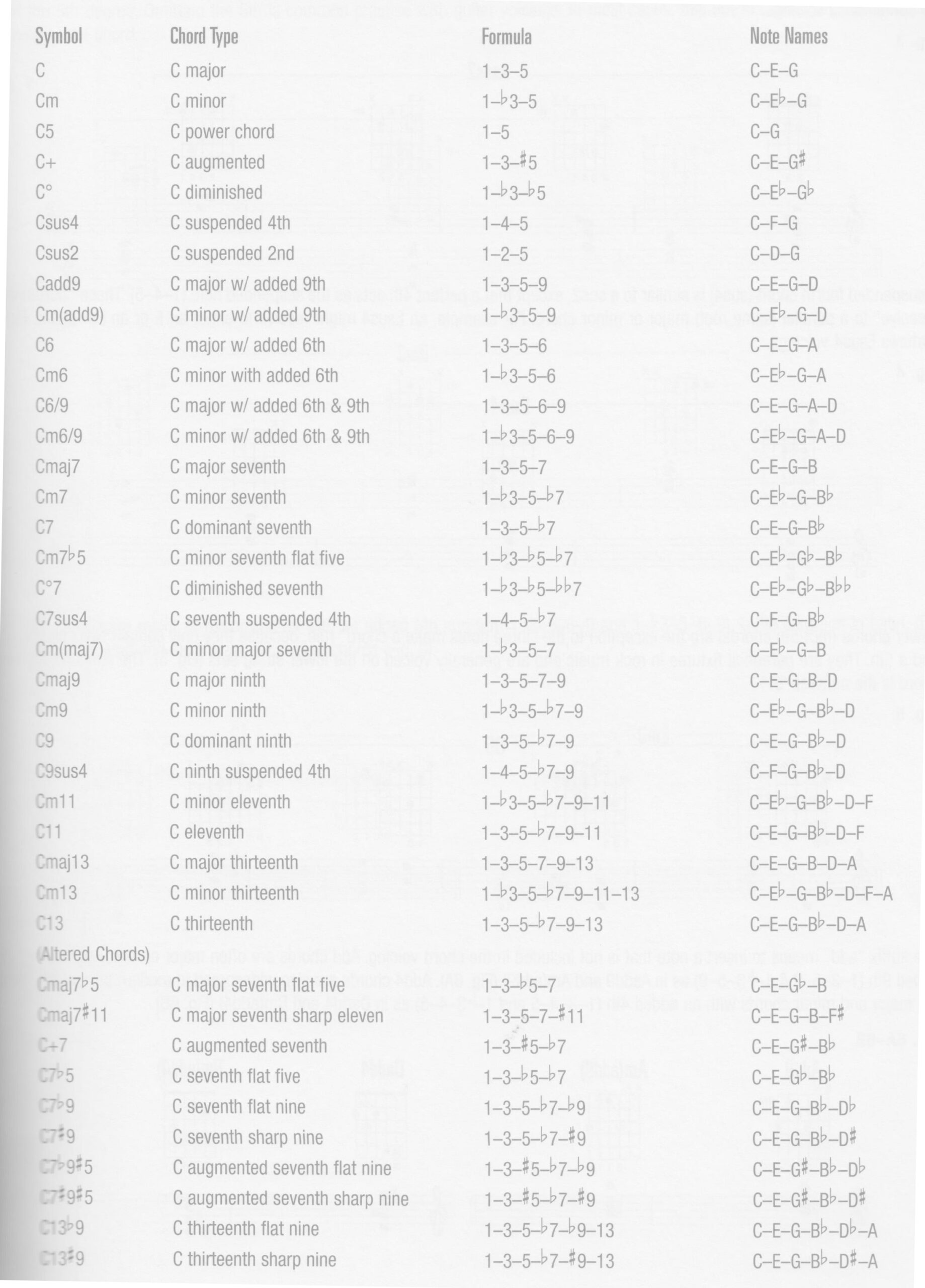

Chapter 7 following on from the harmonized major scale get to construct a whole load more chords with different names by modifying the basic 1-3-5 formula.

P41 Chord names

Power chords are unusual in that they are comprised of only two notes 1-5, the rest are three or more. This does not say anything about the voicings of a chord, the exact notes on the fretboard which are played. Slash chords are sometimes just simplified names for chords which have a complex formal names. There are polychords, indicated by one chord name over another, like a fraction which suggest two chords played together they are not very relevant to guitarists.

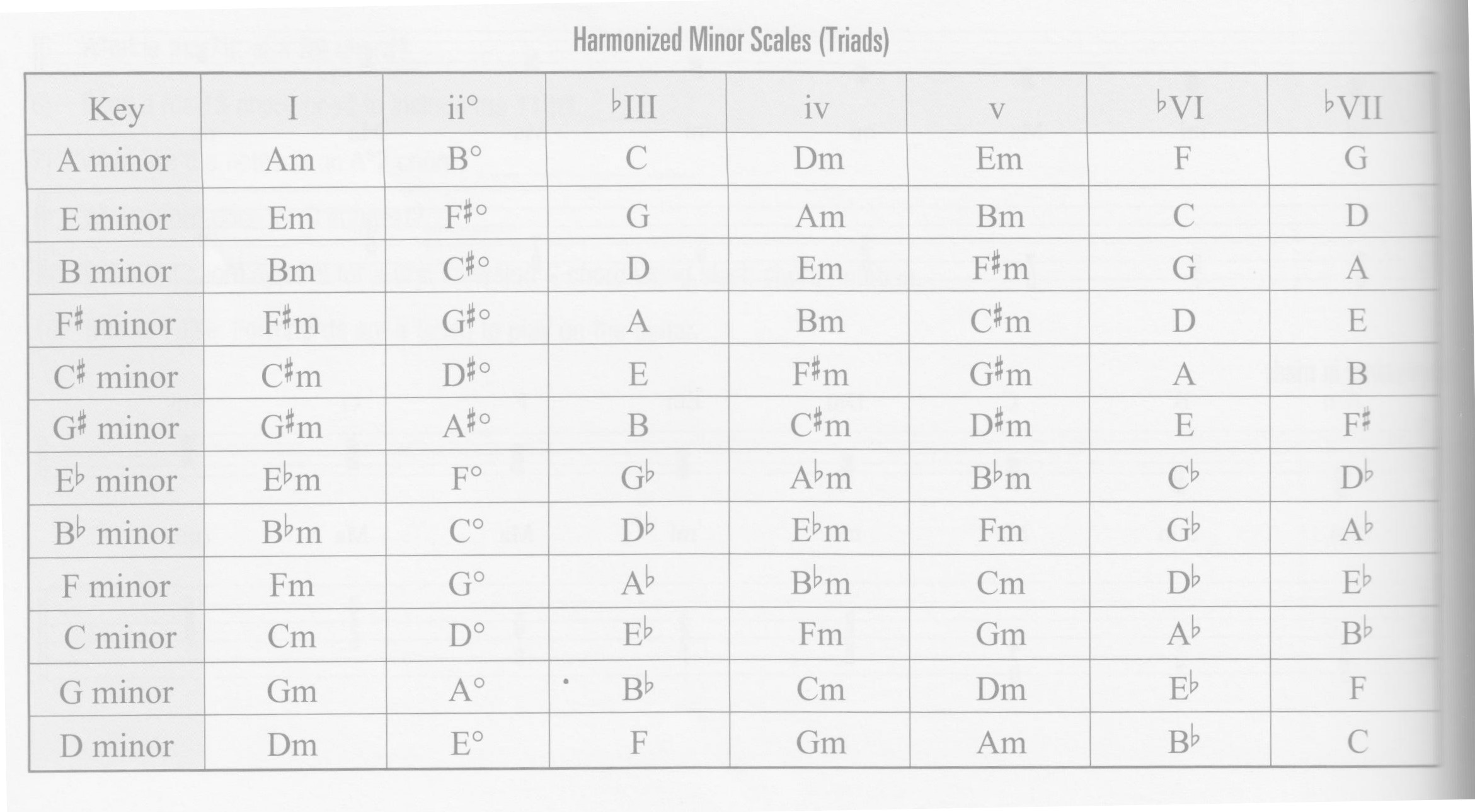

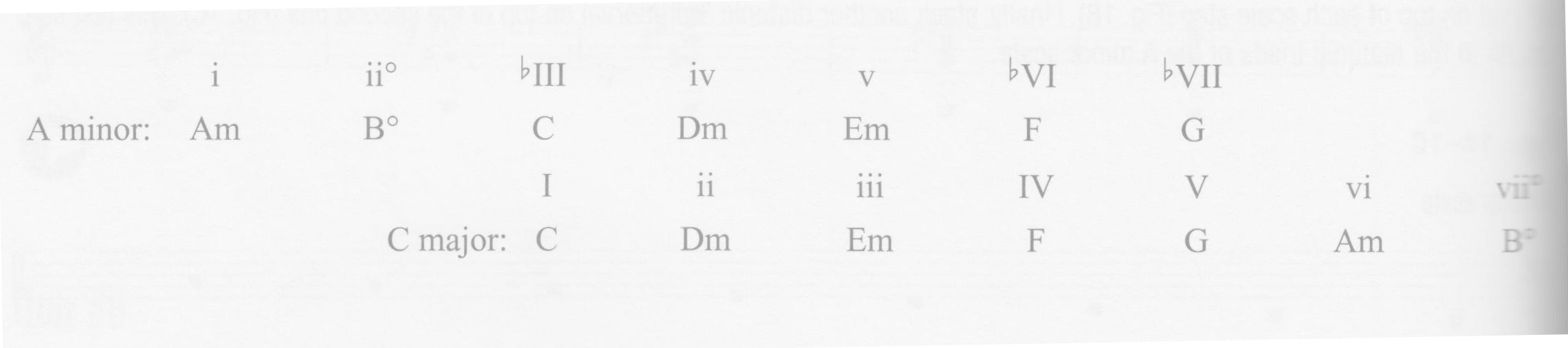

Chapter 8 – we can repeat the exercise of harmonising the major scale for the minor scale. This changes the pattern of major and minor chords. Relative scales such as C major and A minor use the same chords but they take different roles in the chord number sense.

P50 Figure 3 shows how the Roman numerals and chords of the A minor and C major scale relate.

P50 Figure 4 shows the harmonised minor scale

Chapter 9 if we know the scale a set of chords belongs to in a song them we can play notes from that scale as a solo over it. Progressions often start and end on the I chord so we can use that as a clue, and the V chord is distinctive too this seems to be because it is the "dominant" chord. Popular music often sticks with one key centre but other forms of music such as jazz can switch from key centre to key centre but they usually return to the original key centre.

Chapter 10 – the blues doesn’t follow the same scheme as discussed to this point. There are a number of different standard blues progressions based around the I, IV and V chords. The blues makes a lot of use of the minor pentatonic scale

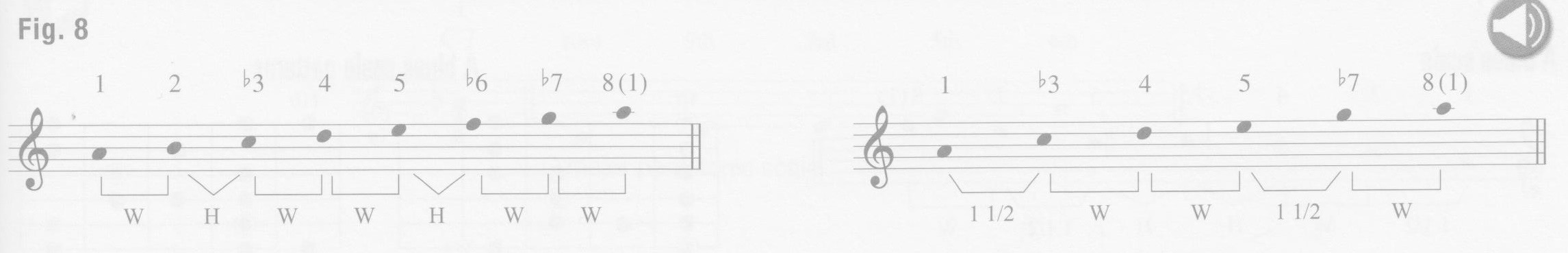

P63 Figure 8 Formula for the pentatonic scale along with the major scale for comparison

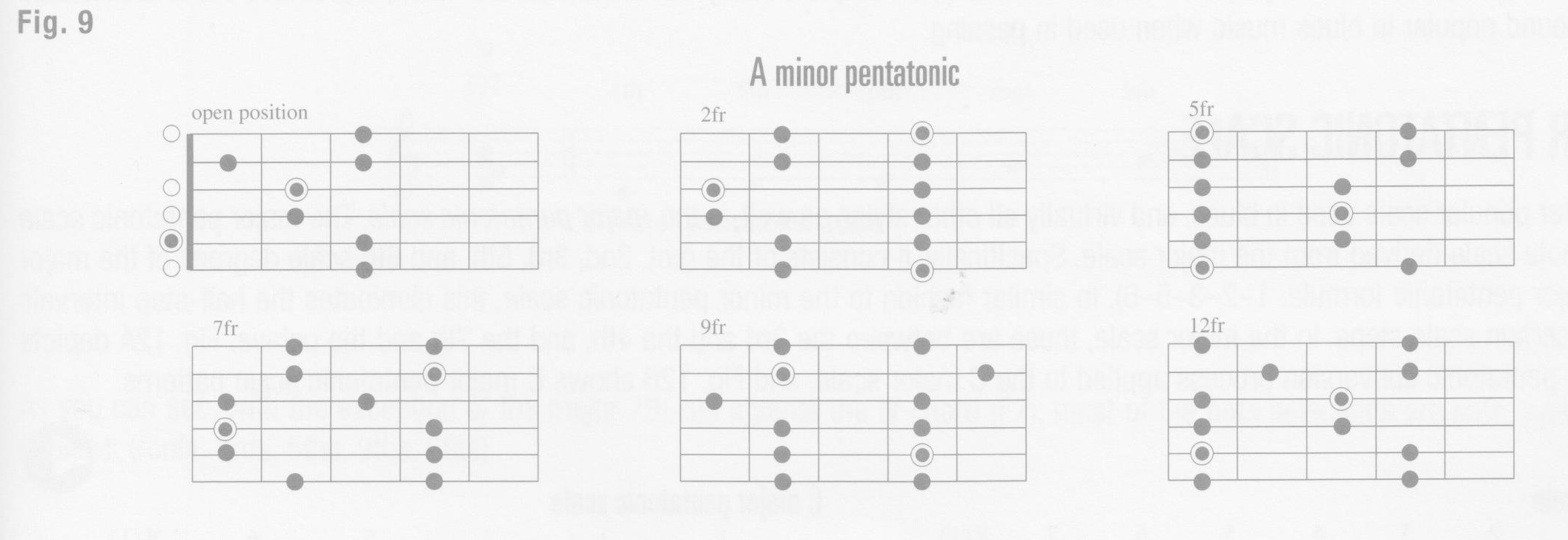

P63 figure 9 A minor pentatonic scale at different positions on the fretboard

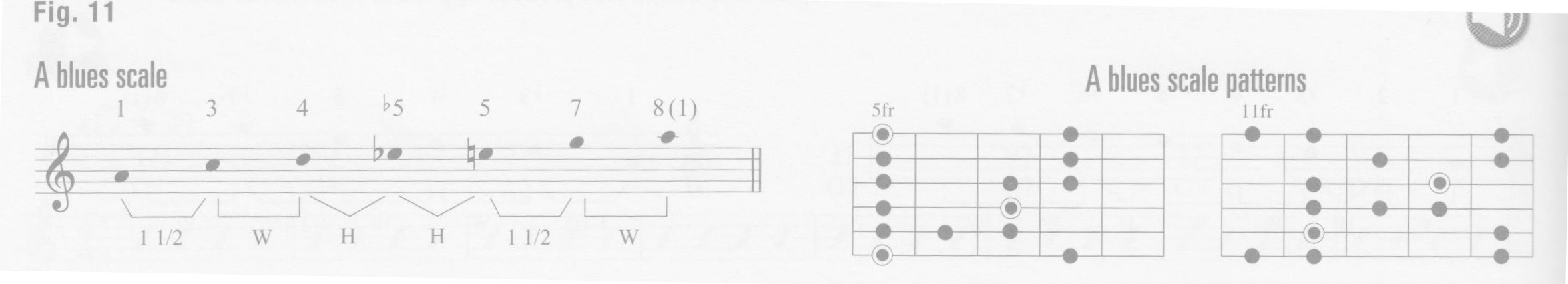

The blues scale has a different formula again, handily the formula and the scale at the 5th and 11th frets are shown in the same figure for the A blues scale. We should play notes from this scale of the A7(I), D7(IV) and E7(V) chords.

P64 Figure The blues scale formula with positions on the fretboard.

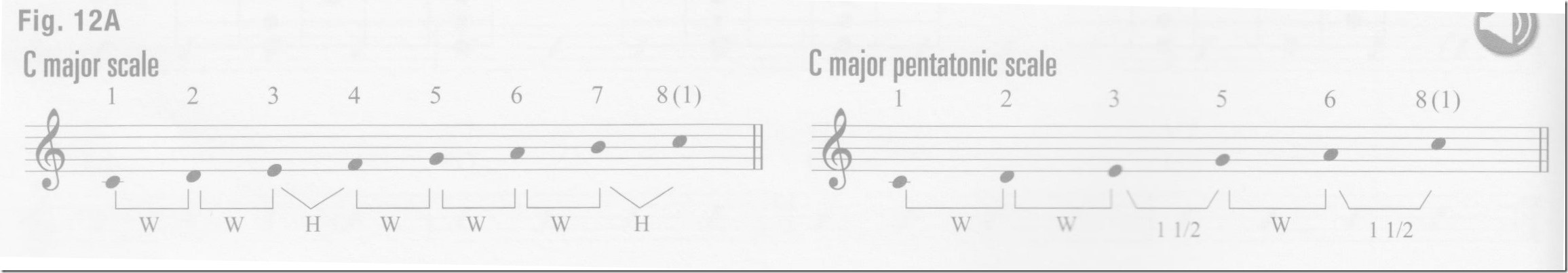

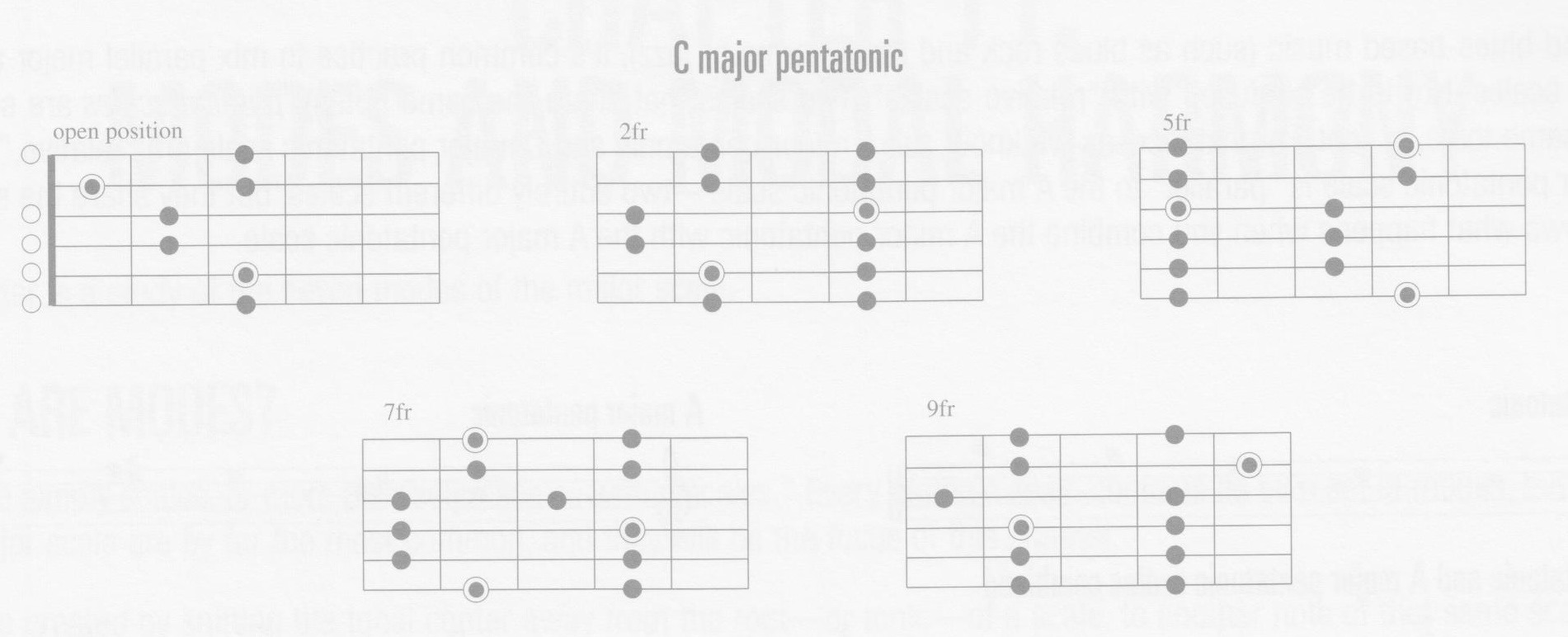

There is also a major pentatonic scale.

P64 Figure 12A The formula for the C major scale and the C major pentatonic scale, compared

P65 Figure 12B The C major pentatonic scale at different places on the fretboard.

To make matters more confusing it is not uncommon to mix the major and minor pentatonic scales with the same root together (parallel scales)!

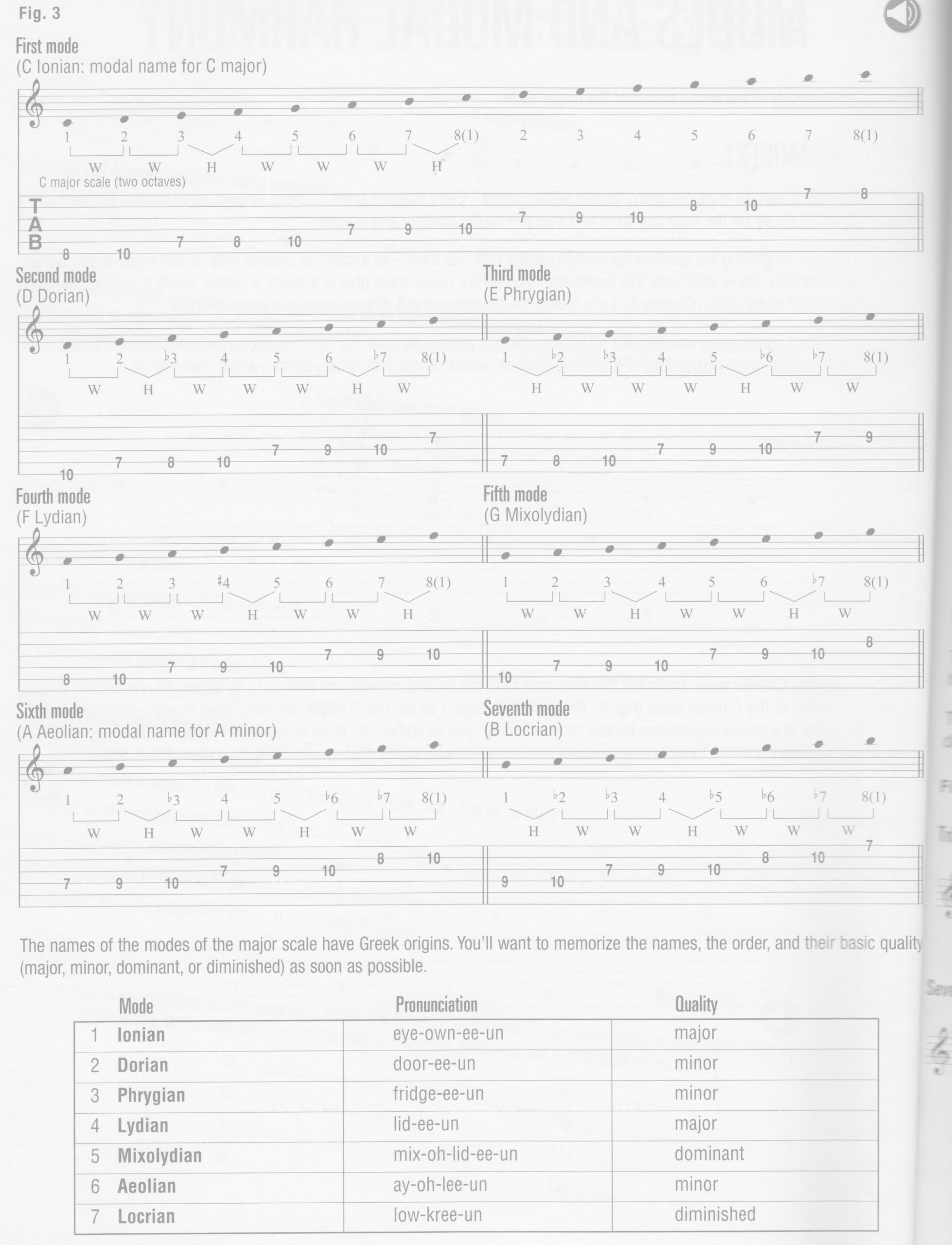

Chapter 11 covers the modes of a scale. Modes of a scale use the same sequence of notes but with a different starting note because they use the same notes they differ from the scale starting at that note. The modes have names Ionian, Dorian, Phyrgian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian and Locrian.

P68 Figure 3 the modes of the C major scale and their notes on the fretboard

The chapter covers each mode, showing formula (notes), construction, category (major, minor etc), differentiating scale degree. chord types, harmony (Roman chord numerals), and common progressions as well has patterns on the fretboard.

Chapter 12 other scales and modes, this starts with an encyclopaedia of further scales, such as the whole tone scale and chromatic scale, showing information similar to that shown for the standard modes. This chapter includes information on arpeggios and how chords relate to scales.

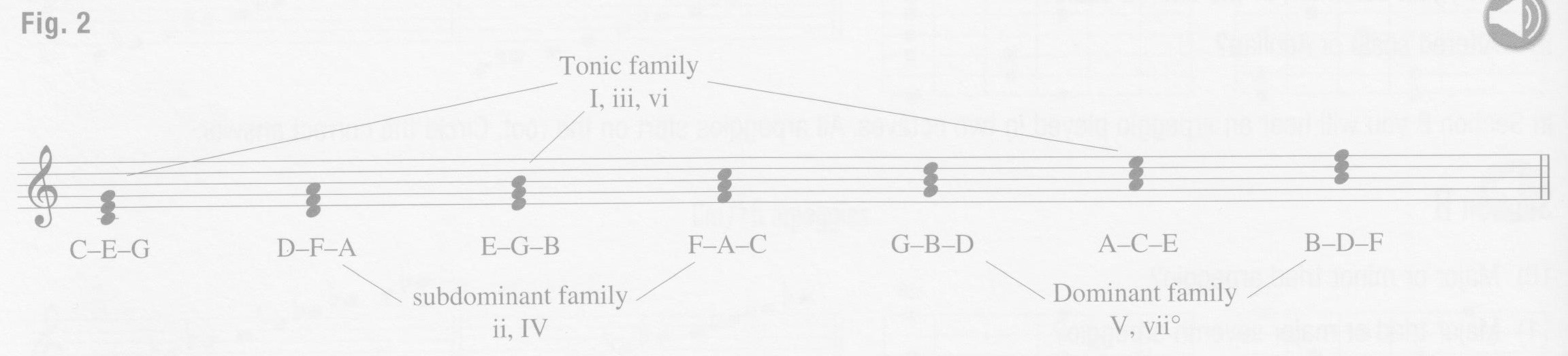

Chapter 13 chord substitution and reharmonization. These appear to be ways of modifying chords, either by changing or adding a note or by substituting chords in a progression. What chords can be substituted for which depends on the family the chord lies in (Tonic, subdominant, dominant). This is one of those places where the function of chords are hinted at, tonic being something that "resolves" the key, IV chords move away from the tonic and V chords move towards it.

P88 Figure 2 Chord families illustrated for the C major scale.

I find it useful to think in terms of computer code, what information do I need to generate the fretboard, scales and chords.

- Fundamentally we need the notes A-A#-B-C-C#-D-D#-E-F-F#-G-G#

- From the notes we can generate the fretboard given there is a half step per fret and the notes on the open strings (E-A-D-G-B-E) – it would be interesting to know which octave a note sits in;

- Using the scale formula I can generate the major, minor, major pentatonic, minor pentatonic and blues scales from the notes;

- Given the harmonisation of a scale I can get the chords in the scale;

- Given the chord compositions (i.e. 1-3-5) I can generate the notes in a chord and the names of the chords;

- There’s probably an interesting exercise in generating chord voicings and scoring them for playability and sound;

- Finally, we can calculate the modes of a scale;

Missing from Music Theory is much description of the "function" chords, these are hinted at in terms of returning to the root chord and resolving tension. Chord progressions and song structure are also not covered.

It seems like the next steps are looking at some of the songs in my songbooks, or tabs on Songsterr and working out which chords are being used and hence which scales, and what the chord progressions are. I should also be able to work out which scales riffs come from. It would be good to learn about song structure too.