This is a post about how I record my research, I write it in the hope that others will reveal some of themselves and perhaps gain something from the writing. I write it because how exactly people work is something of a mystery.

This seems like something I’ve picked up slowly over many years rather than being taught it all in one big bang as an undergraduate. I suspect there may have been attempts to teach me this, but sometimes it takes getting it horribly wrong for you to learn stuff, like the importance of backing up your files.

Clearly scientific literature (including company internal reports) has always been important to my work. I wrote a little bit about scientific publication a while back (here). Generation 1 of my filing system was Windows 3.1’s Cardfile program which I used at the start of my PhD, for each paper I photocopied I typed the details onto an index card. I wrote a sequence number on the corner of each printed paper along with a couple of keywords which I also enter into whatever indexing system I’m using and filed it away in a filing cabinet, ordered by the sequence number. These days most papers are available as PDF and I file this in a directory with the sequence as the first part of the filename.

After Cardfile I moved on to Endnote, and currently I use Reference Manager which are more specialist pieces of software specifically designed for storing the details of publications and also formatting bibliographies in popular wordprocessing packages. Notes on the contents of a paper still get scribbled onto the paper copy in red ink…

These days Zotero and Mendeley both look like good free options for reference management. I haven’t switched to Zotero because it’s currently tied to the Firefox browser and I haven’t switched to Mendeley because I’m not absolutely certain what it is syncing to the Cloud and what other people can see of it there, exposing even the titles of internal company reports to outsiders is a Very Bad Thing. I also had some minor problems importing my legacy collection into Mendeley. Unlike previous iterations of such software Zotero and Mendeley both make reasonable attempts at extracting paper details from PDF files or webpages.

Stray bits of paper scribbled on at meetings I still haven’t really cracked, I try to write the date and a sequence number on any bit of paper I use, and some link to the project it relates too but this is unsatisfying. For many years I’ve considered scanning in bits of paper; our company photocopiers will e-mail scans of paper to you in PDF format and with harddisk space being so cheap now* it seems odd not to do this. All this means I still have a folder per project where bits of paper end up. And, truth be told, I still find it easier to comment on a bit of work by scribbling on a bit of paper.

I’ve started using OneNote a bit for odd note collecting, the OneNote metaphor is of a collection of notebooks, each notebook is divided into sections by tabs along the top of the page and each section is divided further into pages using tabs down the righthand side of the page. My main problem with OneNote is that it’s not possible to display your notes in date order, I seem to use it mainly for a jumping off point to other things.

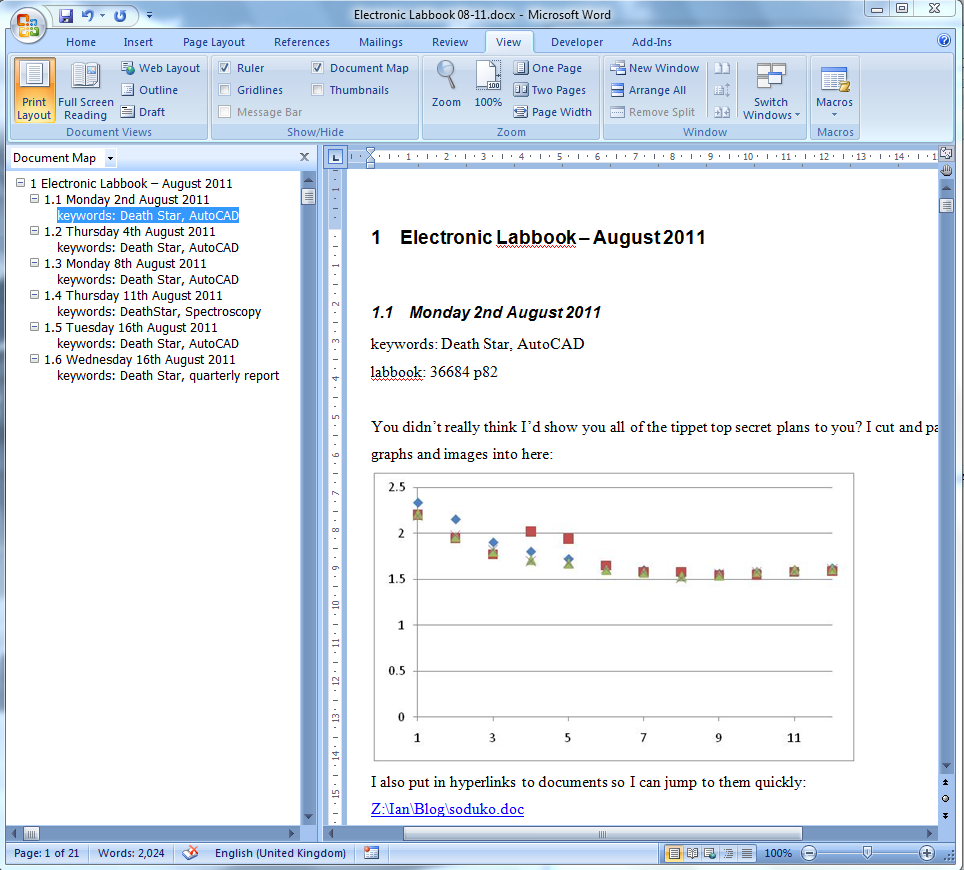

My lab books have been the core of my research since I started my PhD., in my loft there’s a sequence of about 20 of them. Some of my colleagues have fantastically neat lab books with diagrams and graphs carefully sellotaped in and orderly paragraphs describing the experiments done, I never really got that well organised but I did a fair job of adding to an index at the front of each one. I still use paper lab books today but at a reduced rate. I’ve switched to a system using Microsoft Word, for each month I have have a document which looks like the one below:

I can type things in, hyperlink to other documents and cut and paste graphs and pictures as well. I use the Document Map view and, by applying appropriate styling, I get quick links to each day with a view of the keywords for the day – in this instance, designing the Death Star in AutoCAD ;-) For each year I get 12 documents which I store in a folder for that year. The thing I haven’t got working in this system is nice keyword searching across multiple years.

I’ve worked on multiple projects throughout my career and I’ve come to the conclusion that trying to separate them for the purposes of lab books and references doesn’t work too well – you end up spending time working out which lab book / file you should be adding stuff to and with decent indexing it just isn’t necessary.

These days you can buy specialised electronic lab book software, it seems it is normally done at a large scale though rather than by individual which I can’t help thinking is not a good thing since we all have individual ways of working which will vary with both the work we do and our own personal ways of doing things.

Looking at my current electronic lab book it strikes me that WordPress could be used for the task. The thing that Word can’t do easily is to give me rapid links by category or date to any part of my labbook but it strikes me that WordPress does this pretty well if you put the appropriate widgets into the sidebar. I suspect any electronic lab book software is essentially a database with a front end, for WordPress the front-end is written in PHP. The benefit of WordPress is that it’s very widely used, with lots of plugins to provide new functionality and extending it is within the reach of most programmers.

Here endeth the world’s dullest blog post, comments on your own “ways of working” are most welcome!

*Except if you’re in a corporate environment, in which case the laws of every decreasing disk space cost seem to work differently.