This time last year we had a photovoltaic solar power system installed, a few years after we had a thermal solar system installed. This post is an update on how we’ve got on with the photovoltaic solar system. This is facilitated by my weekly collection of electric, solar and gas meter readings – I suspect this data collection is a bit of a minority sport. A couple of months ago the company that the installed the system did offer me a fancy monitoring system… which cost about £1500!

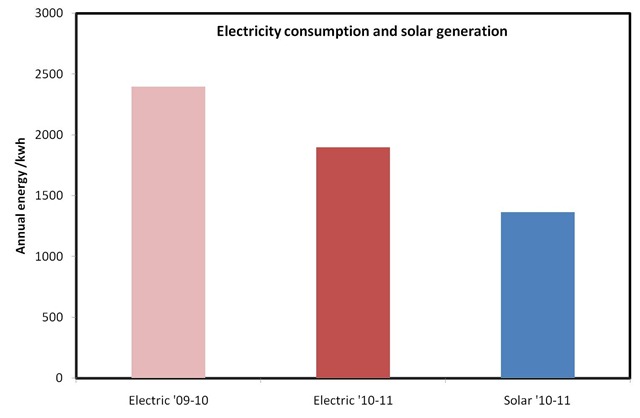

As my earlier blog post highlights the calculated output for our system, given the latitude and orientation of our roof and the peak capacity of our system is 1393kwh per year. The first meter reading was on 28th August 2010, as of 25th August 2011 the reading is 1362.9kwh. So the measured output is 98.5% of the predicted output – not bad at all! Our import from the grid for the same period was 1896.2kwh compared with an annual consumption of 2397.5kwh in the previous year. So a 20% reduction in consumption and generation of 57% of our pre-installation level. The difference here is because our peak generation (mid-late morning) does not match our peak usage (early evening), since we can’t store any electricity the excess goes onto the grid. These figures are illustrated graphically below:

We receive the feed-in tariff and payments for exported electricity from our supplier, npower. This seems to be a small scale operation since to set this up you interact with named individuals who don’t change! So far we’ve received two cheques from them for £105.29 for the period 16/9/10-04/03/11 and £174.38 for the period 4/3/11-21/5/11. I should probably go prod them about whether they want another meter reading.

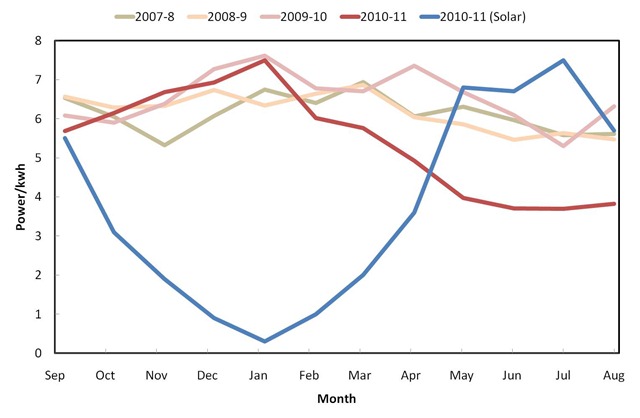

We can dig a little deeper into the data, below I show our monthly electricity consumption (red/green lines) from the grid for the last few years along with the last year of solar generation (the blue line).

Our electricity consumption has been fairly constant through the year with a hint of an increase during the deep winter months due to the shortening days and an increased use of electric lighting. Since about March this year our electricity consumption has been significantly reduced compared to previous years, offset by our solar generation. This pattern wasn’t maintained in the September / October / November last year – I think because I was at home (using electricity) for an extended period following an operation.

Our electricity consumption has been fairly constant through the year with a hint of an increase during the deep winter months due to the shortening days and an increased use of electric lighting. Since about March this year our electricity consumption has been significantly reduced compared to previous years, offset by our solar generation. This pattern wasn’t maintained in the September / October / November last year – I think because I was at home (using electricity) for an extended period following an operation.

The amount of solar generation varies smoothly through the winter months but seems to plateau during the summer. We did have a week of zero generation when the panels were covered in snow. I suspect in principle that the average power generation will vary sinusoidally through the year, since the variation in day length is sinusoidal, but that this can disturbed by “weather”, in particular the figure for May includes the very sunny Easter period without this boost the curve would have varied smoothly through the summer rather than plateauing.

In summary: we’ve generated almost exactly the amount of solar electricity we anticipated which amounts to nearly 60% of our annual consumption of electricity.