gt;

Once again I return to science. Lately I’ve been playing with some calculations of the diffusion of one thing into another. This is for work – can’t say what, it’s top secret ;-) I have to admit I’ve rather enjoyed it.

Once again I return to science. Lately I’ve been playing with some calculations of the diffusion of one thing into another. This is for work – can’t say what, it’s top secret ;-) I have to admit I’ve rather enjoyed it.

Diffusion calculations ultimately amount to an accounting exercise: this is true of much of physics. You have a bunch of stuff of some sort, and you want to calculate where your stuff will be at some time in the future. The stuff may be electric fields, magnetic fields, heat, molecules or atoms but the point is that new stuff can only be created or destroyed following simple rules and stuff will only travel from one place to another according to other simple rules. Largely it’s a problem of conservation – the amount of stuff is conserved, if stuff leaves one place it must turn up somewhere else.

For diffusion the stuff is molecules, for the purposes of these particular calculations the stuff is not created or destroyed. In the crudest case diffusion is just driven by different amounts of stuff in different places, this is enough to drive the redistribution of stuff since at the molecular level everything is jiggling around at random. If you start with more stuff in one place than another and jiggle it all around at random ultimately it ends up uniformly distributed.

Things can get a bit more complicated, for example you might be interested in your stuff moving into a different environment where it’s not so happy to be or your stuff might be reactive but this is just a smallish change in the basic rules. You also need to define an appropriate boundary condition – what your stuff was doing at one instant in time.

The rules and boundary conditions are expressed as a set of equations; these may have an analytical solution – that’s to say you can write down a further equation that specifies where everything is and when (which you can make into a pretty picture for the boss). Or you may have to carry out a numerical solution: divide time and space up into little pieces and apply the rules in small steps – this is an inelegant but frequently necessary method which, if done naively, can bite you on the arse. Or more technically: “exhibit undesirable numerical instability”.

It turns out that the analytical solution for my current problem can be found in Crank’s “Mathematics of Diffusion”, and so the main work was in making a story for those less interested in equations. The fundamental rules for diffusion are elegant and beautiful, the solutions for specific cases can be ugly and a bit hairy. This is where my skill comes in, to be honest I’m not that good at maths so I couldn’t solve the equations myself – but given a bit of time I can work out which equation is the solution to my problem and carry out calculations with it.

My original adventures with diffusion started in the mid-nineties whilst I was a postdoctoral researcher at the physics department in Cambridge – I was funded by Nestle to measure water diffusing into starch. They were interested in this because at the time they were making a KitKat icecream, which involved putting damp icecream next to crispy wafer with the entirely predictable outcome: the wafer went soggy even when the icecream was stored at –20oC. I spent 18 months or so doing experiments and calculations to demonstrate the very obvious which was if you want to stop your crispy wafer going soggy the best thing to do is coat it in something lardy and therefore water-repellent – chocolate is good! In the meantime I learnt a wide range of things about diffusion and experiments.

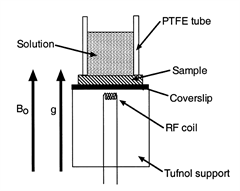

Water diffusing into starch turns out to be a more involved case from a modelling point of view because of the whole “going soggy” thing: basically the properties of the starch change with their water content so there’s feedback between how much water there is and how easy it is for more water to arrive. I did experiments to see where the water was in the starch. This was done using stray-field nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (STRAFI), which required the sample to be stuck on the end of a stick and shoved up the bore of a big magnet, hence the title of this post.

This is another illustration of scientific impact: the core results I relied on for my couple of weeks of calculation date back decades or even hundreds of years. The rules for diffusion were first formulated by Fick in 1855, and since then work has been on-going in solving the equations for ever more complex situations. The 18 months I spent 15 years ago meant that when I returned to it rather then spending several months getting acquainted I could drop pretty much straight in and get some useful results within a couple of weeks. It’s difficult to say what the financial impact for my company might be, with any luck it will save some people at the lab bench a bit of time because results that, are on the face of it, a little odd will have a clear explanation or it may turn out that the calculations show they should stop what they’re doing now because it will never work.

References

- Hopkinson, I., R. A. L. Jones, P. J. McDonald, B. Newling, A. Lecat, and S. Livings. “Water ingress into starch and sucrose : starch systems.” POLYMER 42, no. 11 (May 2001): 4947-4956.

- Hopkinson, I., R. A. L. Jones, S. Black, D. M. Lane, and P. J. McDonald. “Fickian and Case II diffusion of water into amylose: a stray field NMR study.” CARBOHYDRATE POLYMERS 34, no. 1 (December 5, 1997): 39-47.

- Crank, J. “The Mathematics of Diffusion” Oxford Science Publications.