Author's posts

Sep 03 2011

Book review: The Lunar Men by Jenny Uglow

I read “The Lunar Men” by Jenny Uglow a few years ago, this was in a time before blogging so I’d forgotten the contents. I’ve recently reread it, my interest reawakened by my recent reading of the King-Hele biography of Erasmus Darwin. Darwin was a key member of the group of industrialists, inventors, doctors and experimenters based in the West Midlands which finally became the Lunar Society.

I read “The Lunar Men” by Jenny Uglow a few years ago, this was in a time before blogging so I’d forgotten the contents. I’ve recently reread it, my interest reawakened by my recent reading of the King-Hele biography of Erasmus Darwin. Darwin was a key member of the group of industrialists, inventors, doctors and experimenters based in the West Midlands which finally became the Lunar Society.

Uglow lists the principal Lunar men as John Whitehurst (1713-1788), Matthew Boulton (1728-1809), Josiah Wedgewood (1730-1795), Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802), Joseph Priestley (1733-1804), William Small (1734-1775), James Keir (1735-1820), James Watt (1736-1819), William Withering (1741-1799), Richard Lovell Edgeworth (1744-1817), Thomas Day (1748-1789), Samuel Galton (1753-1789).

It’s notable how many of the Lunar Men were Scots, in the mid-18th century England had two universities, Scotland had five.

It’s not until 1775 some 15 or so years after the core group had originally met that the Lunar Society is formalised. At the time arranging events to coincide with the full moon was not uncommon. Alongside the Royal Society there were numerous other local “Philosophical Societies” although I’m not clear of the details of these other groups it seems there was nothing exceptional about the Lunar Society in terms of the mix of people but they were rather exceptional people. They were proactive in seeking out new members, for example Withering was recruited on the death of William Small. As gradually the founding members died, the group dissolved in 1813.

Matthew Boulton, owner with John Fothergill of the Soho Manufactory, started as a maker of “toys” (which in this case means any number of small metal items) and non-ceramic ornaments but he collaborated with James Watt to make stream engines. He was later to set up the Soho Mint, which used patented pressing equipment to make high quality coins and medals in bulk.

James Watt made his first breakthrough in the design of steam engines in 1765 but it wasn’t until 1775 that they received a 25 year extension of the key patent and in 1776 they install their first engine in Cornwall. The revenue from these engines came in the form of a fee related to the cost savings on coal which the more efficient design of the Watt engine provided compared to the Newcomen atmospheric engines, introduced in the early 1700s. The protection and creation of patents was an important part of the Watt and Boulton business plan, they even supported Richard Arkwright, with whom they did not see eye to eye, in the protection of his patents for the cotton processing equipment at the heart of his factory. Patents are one route to deriving income from intellectual property, the newly formed Society of Arts offered another route: prizes, or premiums, for named topics which centred around manufacture.

On the face of it the presence of Josiah Wedgewood, a potter, in the group seems odd but reading the book it becomes obvious just how high-tech an industry the potteries were. Clay is not simply dug up from any old patch of ground and flung on a wheel – the correct raw materials must be selected and once this is done they must be processed properly before they can be formed into shapes. Even then it isn’t over: the process of applying glazes and firing the ceramics is far from straightforward. The ceramic industry was one of the high tech industries of its time, an 18th century Silicon Valley.

Boulton and Wedgewood were both in the business of mass producing desirable consumer goods and marketing them to the middle classes. They recruited excellent artists to produce designs, often based on classical themes and objects. Initially selling them to the very wealthy but with a view to mass production and the use of their aristocratic clients as promotional material. For Wedgwood the culmination of this was the creation of replicas of the Portland Vase.

Alongside the factories growing up in the Midlands came the canals with which the Lunar Men were heavily involved. The canals brought freight costs down from 10d per mile to 1.5d per mile. They started to replace the turnpike roads and river navigations, both enabled by acts of parliament which gave rights to maintain roads and rivers to corporation – along with the right to raise tolls. This previous incarnation of transport seems to have been initiated around 1650. By the mid-19th century a full-scale rail network was in place, replacing in turn the canals. The canals meant that raw materials could be moved around more cheaply, and that expensive (and delicate) manufactured goods could be shipped out.

The Lunar Men had a range of political views, although Uglow comments that scientific experimentation was more associated with Whigs than Tories. The manufacturers, Boulton and Wedgwood, were notably less radical most likely with an eye to maintaining the political support required to keep their businesses running, although Boulton in particular was pretty progressive in the treatment of his workforce. Many of the group were supportive of the French Revolution, American independence and the abolition of slavery. Priestley was a Dissenting preacher, and when the backlash against all manner of radical thought came his house was one of 30 or so properties singled out for attack during the 1791 Birmingham Riots, Withering’s house was also attacked.

The scientific context is quite different compared to today: public demonstrations of cutting edge science including electrical demonstrations were common and a group of educated gentlemen could make valuable contributions to science as amateurs doing the work in their spare time. Withering and Darwin fought over the discovery of digitalis as a well-defined medical material. Priestley was probably the most impactful “scientist” of the group being one of several who played a key role in the discovery of oxygen and it’s properties. Darwin was largely a “scientist” who suffered from having ideas before his time particularly with regard to evolution but also his ideas on meteorology were in advance of his time. Others in the group such as Watt and Keir were clearly entirely competent in scientific areas.

Strangely I found the King-Hele biography of Erasmus Darwin pretty much as informative on the Lunar men as this book and more readable – perhaps because it’s more difficult to write a compelling narrative around a, sometimes loose collective, compared to an individual. I am now intrigued about the evolution of factories in the 18th century and, more disturbingly, 18th century intellectual property rights.

Sep 02 2011

Friday rant

t-mobile get the pointy end of this because they come at the end of a day wherein I was assailed from all sides by idiocy.

18 months ago I became the proud father of Shiny, an HTC Desire phone on a contract for £20 per month, a novel experience for me. Shiny is mainly used as a internet access device rather than a speaky texty phone and I’ve been very happy with it.

So at the end of 18 months I am free of my original contract to t-mobile and can seek something cheaper, the key thing being unlimited* internet access. I look on the t-mobile website: it says they’ll offer me £6 off my contract going forward for a 12 month lock-in or some such. Carphonewarehouse, on the other hand, offers me a £10 per month SIM Only contract with t-mobile on monthly rolling basis, oddly 12 month contracts are £15. This, anyway, is a “no-brainer”, I get a monthly rolling SIM only contract with t-mobile contract for £10 which is less than the t-mobile renewal offer of £14. This requires a conversation with carphonewarehouse’s call centre which sounds a little cramped because I can hear my man Paul’s neighbour demanding a stapler and another having somewhat groundhog-day sounding conversation about “which shop did you get this better offer in?”

Anyway this is sorted, all I need to do is ring up t-mobile once my new SIM card is delivered and get my number transferred from my old account to my new one. Apparently this requires t-mobile to provide my PAC number to themselves (don’t ask me!).

Fail one is that on ringing the t-mobile 150 service I get a list of numeric options: I need option 2 but the service doesn’t recognise my many and creative ways of pressing the 2 key on my keypad. Actually it’s a softkey rather than an actual real key but it had 2 written on it so I pressed it.

By pressing 1 I get through to an actual person who establishes that I need transferring to their cancellation department – you see I currently have two contracts with t-mobile and I want to cancel the old one and transfer the number to the new one, as an interesting aside the chap at carphonewarehouse told me my credit rating is so good I can have 4 contracts! The person I’m talking to has a pleasant Irish accent although I can’t help thinking she is actually an Indian who has been trained to speak with an Irish accent to reassure me#.

After waiting on hold for a few minutes I get another person this time with a pleasant Welsh accent (proviso as above), anyway she tells me I “can’t” transfer my phone number from one t-mobile account to another. Now I’m a bit hardline on these things: I can transfer a number from a non-t-mobile account to a t-mobile account by invocation of the PAC number therefore logically I “can” do the described transfer therefore “can’t” actually means “won’t”. However, it turns out that I can convert my existing contract to a £5 per month contract equivalent to my new SIM only contract but with a 24 month contract period. Needless to say this was not visible on any website. We agree to do this.

So at the end of two rather complex phone calls I have reduced my phone bill from £20 per month to £5 per month (actually £6 with VAT). I do have a PhD, and whilst this may not endow me with great nouse, it does mean I’m not a dribbling idiot – yet to me this process has been ridiculously Byzantine and complex. It’s taken me two 20 minute phone calls to do what should be a couple of button presses.

I do feel sorry for the poor souls that inhabit these call centres because I’m actually a polite sort of chap but the wrangling I have to engage in does make even me a bit tetchy and they, through no fault of their own, get the pointy end of that.

Addendum

Wednesday and I’ve just had a chat with t-mobile again, because my online account info doesn’t match what I agreed on the phone on Friday, currently it indicates that my contract is for £8.51 per month exc VAT and that I don’t have the farcically named “unlimited” internet access I signed up for. They assure me that when I get my next bill it will be for £5 plus VAT and the required “unlimited”.

The problem here is that they’ve sent me several messages telling me how great their online account info system is, meaning I’ve gone off and looked at it. What they’re actually trying to do is hide how little they’re willing to charge me for a mobile phone contract. This is all explained nicely in Tim Harford’s book “The Undercover Economist“, the trick is to find out the maximum someone is willing to pay for a service and offer it to them, without prejudicing your efforts with other customers who have a higher maximum price. Price transparency would spoil this game.

Footnotes

*for values of internet access which are limited; actually how do they get away with describing limited internet access as “”unlimited”?

#Personally I don’t care that the call centre might be in India but I am offended that they feel the need to fake an accent to “reassure” me. It’s quite possible that t-mobile’s call centres are actually in England and I have maligned an Irish lady and a Welsh lady.

Aug 30 2011

Photovoltaic solar power – one year on

This time last year we had a photovoltaic solar power system installed, a few years after we had a thermal solar system installed. This post is an update on how we’ve got on with the photovoltaic solar system. This is facilitated by my weekly collection of electric, solar and gas meter readings – I suspect this data collection is a bit of a minority sport. A couple of months ago the company that the installed the system did offer me a fancy monitoring system… which cost about £1500!

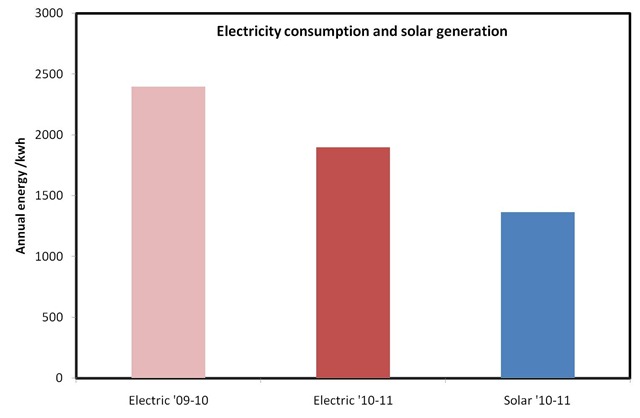

As my earlier blog post highlights the calculated output for our system, given the latitude and orientation of our roof and the peak capacity of our system is 1393kwh per year. The first meter reading was on 28th August 2010, as of 25th August 2011 the reading is 1362.9kwh. So the measured output is 98.5% of the predicted output – not bad at all! Our import from the grid for the same period was 1896.2kwh compared with an annual consumption of 2397.5kwh in the previous year. So a 20% reduction in consumption and generation of 57% of our pre-installation level. The difference here is because our peak generation (mid-late morning) does not match our peak usage (early evening), since we can’t store any electricity the excess goes onto the grid. These figures are illustrated graphically below:

We receive the feed-in tariff and payments for exported electricity from our supplier, npower. This seems to be a small scale operation since to set this up you interact with named individuals who don’t change! So far we’ve received two cheques from them for £105.29 for the period 16/9/10-04/03/11 and £174.38 for the period 4/3/11-21/5/11. I should probably go prod them about whether they want another meter reading.

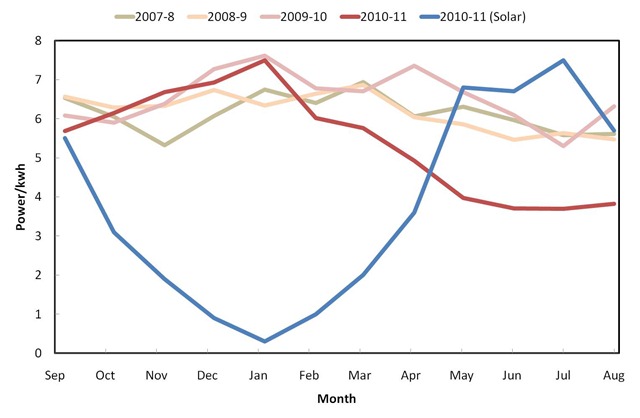

We can dig a little deeper into the data, below I show our monthly electricity consumption (red/green lines) from the grid for the last few years along with the last year of solar generation (the blue line).

Our electricity consumption has been fairly constant through the year with a hint of an increase during the deep winter months due to the shortening days and an increased use of electric lighting. Since about March this year our electricity consumption has been significantly reduced compared to previous years, offset by our solar generation. This pattern wasn’t maintained in the September / October / November last year – I think because I was at home (using electricity) for an extended period following an operation.

Our electricity consumption has been fairly constant through the year with a hint of an increase during the deep winter months due to the shortening days and an increased use of electric lighting. Since about March this year our electricity consumption has been significantly reduced compared to previous years, offset by our solar generation. This pattern wasn’t maintained in the September / October / November last year – I think because I was at home (using electricity) for an extended period following an operation.

The amount of solar generation varies smoothly through the winter months but seems to plateau during the summer. We did have a week of zero generation when the panels were covered in snow. I suspect in principle that the average power generation will vary sinusoidally through the year, since the variation in day length is sinusoidal, but that this can disturbed by “weather”, in particular the figure for May includes the very sunny Easter period without this boost the curve would have varied smoothly through the summer rather than plateauing.

In summary: we’ve generated almost exactly the amount of solar electricity we anticipated which amounts to nearly 60% of our annual consumption of electricity.

Aug 27 2011

Living in code

Eric Schmidt, chairman of Google is in the news with his comments at the MacTaggart Lecture at the Edinburgh International Television Festival. The headline is a general criticism of the UK education system but what he actually said was more focussed on technology and in particular IT education: bemoaning the fact that computer science was not compulsory and what of it that there was about the use of software packages rather than how to code.

I was born in 1970, and learnt to program sometime in the early 80s. I can’t remember exactly where but I suspect it was in part at the after-school computer club my school ran. A clear memory I have is of an odd man who’d brought in a TRS-80 explaining that a FOR-NEXT loop was an instruction for a computer to “go look up its bottom” – this was at a time before CRB checks. My first computer was a Commodore VIC-20, Clive Sinclair having failed to deliver a ZX81 and the BBC Micros being rather more expensive proposition than my parents were willing to afford.

Many children of the early 80s cut their teeth programming by typing in programs from computer magazines; a tedious exercise which trained you in accurate transcription and debugging. Even at that time the focus of Computer Studies lessons was on using applications rather than teaching us to program although I do remember watching the BBC programmes on programming which went alongside the BBC Micro. As I have mentioned before, programming is in my blood – both my parents were programmers in the 60s.

About 10 years ago I was teaching programming to undergraduate physicists, from a class of 50 only 2 had any previous programming experience. The same is true in my workplace, a research lab where only a small minority of us can code.

Knowing how to code gives you a different mindset when approaching computer systems. Recently I have been experimenting with my company reports database. The reports are stored as PDF files; I was told the text inside them was not accessible – now to me that sounds like a challenge! After a bit of hacking I’d worked out how to extract the full text of reports out of the PDF files but then code that once worked stopped working. This puzzled me, so I checked the text that my program was pulling from the database and instead of being a PDF file, it was a message saying “Please don’t do that"!

At the moment I’m writing a program that takes an address list file, checks to see if the addressees have a mobile phone number and if they do uploads it to an SMS service, spitting out into a separate file those that do not have a mobile phone number. To me this is a problem that has an obvious programming solution, for the people who generate the address list it’s a bit like black magic.

These days we are surrounding by technology bearing code, just about every piece of electrical equipment in my house has code in it, but it seems that ever fewer of us have been inducted into the magic of writing our own code. These days there’s just so much more fun to be had from programming: there are endless online data sources and our phones and computers have so many programmable facilities built into them.

At what age can I teach my child Python?

Aug 24 2011

The British sport of bashing the bankers

It’s very popular these days to blame the “bankers” for the recession, and indeed “bash the bankers”. No doubt some of this enthusiasm is down to the fact that “bankers” sounds a bit like “wankers”, and many gain a simple pleasure from this recognition.

Finance (or banking) meant that I could afford to buy a house costing £50,000 with a salary of only £25,000 (this was some time ago!), and investment means that companies wishing to grow can do so without having to painstakingly build up cash reserves by trading. Dealing in these investments is what will help pay for my retirement through my pensions – this is true for both my Universities Superannuation Scheme and my company pension. Insurance helps us to cope with financial shocks we could not otherwise bear, the premiums for this insurance are often invested so reducing the amount of the premiums.

Banking is a mild confidence trick, it generates extra cash on the basis of anticipated future income. The crash happened because banks lent to people who, it turns out, couldn’t realistically be expected to provide that future income. On realising this the banks found they had promised the provision of rather more money than they had access to and flapped around trying to call that money in. More specifically, in the US, banks were giving mortgages to people who didn’t have jobs but who could “afford” a mortgage because “of course” the value of the properties was always going to increase and so the interest on the mortgage would be covered by the rising house value. This scheme worked because these dodgy mortgages were bundled up together and then traded. The bundling reduces the risk, as long as there is no systematic shock that effects all of the mortgages in the bundle.

The bank bailout was not a cash gift in the sense that you might give me £50 for my birthday, it was money to give the banks confidence to keep lending out money which many of us need to live in the manner to which we have become accustomed. In a way the current lending targets for banks are perverse: we’re in the position we are in now because the banks lent more generously than was wise – now we’re encouraging them to lend more than they would otherwise wish.

The bank hardest hit by the crash in the UK was Northern Rock, not a bank engaging in particularly aggressive or exotic trading, rather one that gave the opportunity of owning a house to rather more people than it was strictly wise to do so. In retrospect you could see the seeds of this over-lending 10 years ago, when I was offered a mortgage 4x joint salary, or when you saw all those programs featuring people in their twenties who had £20,000 and above on credit card bills built up on purchases they didn’t need and couldn’t afford.

This isn’t to say the financial sector is without faults: they have a habit of selling products to people who don’t need them (like that mortgage protection plan you sold me Cheltenham and Gloucester), they invent financial abstractions which no-one has a hope in hell of understanding and, because they preside over large money flows, they are able to pay themselves very nicely by extracting a small charge from those vast flows whilst many people are not doing so well.

For me this is personal: my brother has worked in the IT departments of several investment banks, currently the town where I live is facing the possibility of 3,500 job loses because the Bank of America may be closing its credit card handling centre. I don’t want the 3,500 or the one to lose their jobs.

It’s easy for politicians to piggy-back on this enthusiasm for banker bashing but we should be aware that many of the things we take for granted are built with the support of the financial industry.