Author's posts

Apr 22 2011

L’Académie des Sciences

I’ve written a number of times on the Royal Society, Britain’s leading and oldest learned society, often via the medium of book reviews but also through a bit of data wrangling. This post concerns the Académie des Sciences, the French equivalent of the Royal Society. It has gone through several evolutions, and is has been one of five academies inside the Institut de France since its founding in 1795. As a physical scientist the names of many members of the Académie are familiar to me; names such as Coulomb, Lagrange, Laplace, Lavoisier, Fourier, Fresnel, Poisson, Biot, Cassini, Carnot …

The reason I’m interested in scientific societies is that, as a practitioner, I know they are part of the way science works – they are the conduit by which scientists* interact within a country and how they interact between countries. They are a guide to who’s hot and who’s not in science at a particular moment in time, with provisos for the politics of the time. As I have remarked before much of the “history” taught to scientists comes in the form of Decorative Anecdotes of Famous Scientists, this is my attempt to go beyond that narrow view.

The Académie des Sciences was founded in France in 1666 only a few years after the Royal Society which formally started in 1660. It appears to have grown from the group of correspondents and visitors to Marin Mersenne. In contrast to the Royal Society it was set up as a branch of government, directed by Jean-Baptiste Colbert who had proposed the idea to Louis XIV. The early Academy ran without any statutes until 1699 when it gained the Royal label. The Academy was based on two broad divisions of what were then described as mathematical sciences (astronomy, mathematics and physics) and “physical” sciences (anatomy, botany, zoology and chemistry) within these divisions were elected a number of academicians, and others of different grades. Numbers were strictly limited: in 1699 there were 70 members and even now there are only 236. Unlike the Royal Society, funded by member subscriptions, the Academy was funded by government – giving a number of generous pensions to senior academicians to conduct their scientific work.

The Academy avoided discussion of politics and religion, echoing the founding principles of the Royal Society, and was explicit in making links to foreign academics giving them the formal status of correspondent. This political neutrality was sustained through the French Revolution: although the Academy was dissolved for a few years at the height of the Terror and was subsequently reformed with essentially the same membership as before the revolution. Furthermore work on revising the French system of weights and measures carried on through the Revolution.

The Scholarly Societies Project has an overview of publications by- and about the Academy. The earliest scientific papers of the Academy appear in “Journal des Sçavans”, which commenced publication in 1665, shortly before the “Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society” and therefore the earliest scientific journal published in Europe. From 1699 a sequence of work is published in “Histoire de l’Académie royale des sciences” until 1797. Finally “Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences” has been published since 1835. Most of which are freely available as full-text digitized editions at Gallica (the French National Library).

The British government established the Longitude Prize in 1714, by act of parliament, to award the inventor of a simple and practical method for determining the longitude at sea. Subsequently Rouillé de Meslay invested a similar prize for the Academy, which commenced in 1720. This sequence of Academy prizes was awarded yearly to answer particular questions and alternated between subjects in the physical sciences and subjects in navigation and commerce. Those in commerce and navigation revolved around shipping: with questions on anchors, masts, marine currents and so forth. These prizes were open to all, not just members of the Academy. Subsequently the Academy became a clearing house for a whole range of prizes, these are described in more detail in “Les fondations de prix à l’Académie des sciences : 1714-1880” by E. Maindron.

In summary, although similar in their principles of supporting science, scientific communication and providing scientific support to the state and commerce the Royal Society and the Académie des Sciences differ in their internal structure and relationship with the state. The Academy being more closely aligned and funded by the state, certainly in formal terms, and rather more limited in its membership.

In common with the Royal Society the membership records of the Académie are available to play with and in common with the Royal Society they are in the form of PDF files which are a real pain to convert back into nicely structured data. I could engage in a lengthy rant on the inequities of locking up nice data in a nasty read-only format but I won’t!

Footnotes

- Image is “Colbert présente à Louis XIV les membres de l’Académie Royale des Sciences crée en 1667” by Testelin Henri (1616-1695)

- *Yes, Becky, I know you don’t want me to use “scientist” in reference to people living before the term was first coined in the 19th century ;-)

References

MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive is the best English language resource I’ve found on the Académie des Sciences. Winners of the Grand Prix can also be found on this site.

Apr 16 2011

The elephant in the room

In my last blog post I wrote about the AV referendum and party political self-interest. Before that I wrote about AV, preference and how parties hold their internal elections.

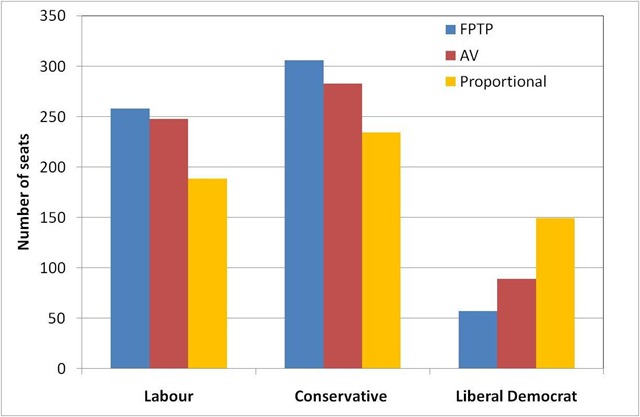

In this post I will just explain the chart at the top of the page.

It shows the number of parliamentary seats each of the three main national parties gained in the UK 2010 General Election under first-past-the-post (FPTP) – these are the blue bars. The red bars show the number of seats each party would expect to gain under Alternative Vote (AV), based on a mock election involving 13,000 people. Finally the yellow bars show the number of seats which would be obtained under a proportional system.

The proportional system, where the number of seats is proportional to the number of votes gained nationwide, is what I would call “fair”.

Labour and Tory parties both benefit significantly under the current FPTP system and proposed AV systems.

Apr 14 2011

Self-interest and electoral perversions

In this post I will argue that all of the political parties are arguing the case for AV in their own self-interest, this is very obviously what they are doing and admitting such will make a change.

I’d like to start with the electoral system as it stands today:

Two things are going on at an a general election: there are “local” elections in 650 constituencies which determine which individual represents each constituency in parliament and then there is the government formed as the result of this set of elections. Once elected to parliament MP’s represent their constituents interests but vote largely as whipped by their political party.

First past the post (FPTP) and Alternative Vote (AV) are both algorithms for determining local representation: they make no deliberate effort to make the output of a collection of constituencies proportional to the proportion of votes cast for a particular party across the country. The degree to which they give proportionality is dependent on the spatial distribution of voters for each party across the country and the locations in which electoral boundaries are drawn1. The current distribution of party support is not far off the point where it can give completely perverse results with the Liberal Democrats gaining the largest fraction of the popular vote and the fewest parliamentary seats and Labour gaining the smallest fraction of the popular vote and the largest number of parliamentary seats2.

The FPTP system acts to supress the formation of more than two political parties, this is known as Duverger’s law. You can see this in action in the UK, with the separation of the SDP from Labour in the early 1980’s, gaining a large fraction of the popular vote: approaching that of Labour, but nothing like the same number of seats3.

Best estimates for AV in a UK general election are that the Liberal Democrats will gain seats in a Westminster election and Labour and the Tories will lose some, it isn’t particularly clear who will lose most.

So moving on to the self-interest of parties:

The Liberal Democrats are in favour of AV because they will get more seats, this is OK because they will still have far fewer seats than their proportion of the vote should allow.

The Tories are against AV because they believe that they will lose seats to the Liberal Democrats for the same share of the vote, and that Labour-Liberal Democrat coalitions are more likely than Tory-Liberal Democrat coalitions. Wait! What?

Labour is split on AV, this is because some believe that Labour-Liberal Democrat coalitions are more likely than Tory-Liberal Democrat coalitions, and the Tories could be basically locked out of power for ever. Others in Labour, on the left of the party, believe that the Socialist utopia should be pure and that coalition is anathema and so oppose AV.

UKIP is in favour of AV because they believe that they will be first preference for a number of people who vote Tory tactically and second preference for a number of Tories. Their visibility will rise, even if it doesn’t lead to much increase in seats.

The Greens are in favour of AV because they believe they will pick up second preferences from Liberal Democrats and Labour.Their visibility will rise, even if it doesn’t lead to increased seats.

The BNP is against AV because it judges that it will not pick up second preferences from anyone. It decreases the likelihood of them gaining seats even if it increases the visibility of the party. The BNP is entirely visible already but for the wrong reasons.

Oddly those on either side of the debate are able to draw on arguments that match the self-interest of their parties. What is the non-aligned voter to make of this?

Footnotes

- Oxford is a nice example of this: across the two Oxford parliamentary seats (Oxford East and Oxford West and Abdingon) the number of votes for the three main parties are (LibDem: 41087, Tory: 33633, Lab: 27937. The two constituencies return a Labour and a Tory MP.

- Don’t believe me? Put Tory: 33.2%, Labour: 27.2%, LibDem: 27.7% Other: 11.9% into this BBC seat calculator. The actual result was Tory: 36.1%, Labour: 29.0%, LibDem: 23.0% Other: 11.9%

- The 1983 General Election. Vote share: Tory: 42.4% Labour: 27.6% SDP+Liberal Alliance: 25.4% Number of seats: Tory: 397 Labour: 209 SDP+Liberal Alliance: 23.

- Given 1-3, on what basis is it that we claim to live in a democracy?

Apr 11 2011

Yes to AV!

Alongside the local elections on the 5th May, we will all have an opportunity to vote in a referendum on voting reform*. The choice is between keeping the current system, First Past the Post (FPTP) or switching to the Alternative Vote (AV) system.

The Liberal Democrats use Single Transferrable Vote (STV) to elect their leaders. Labour uses straightforward AV. The Tories use a system to elect their leader which is substantially equivalent to AV: a ballot is taken with all candidates standing; if more than two candidates are standing then the last placed candidate is knocked-out and the ballot is repeated – this process is continued until only two candidates remain. In this two candidate election the candidate with most votes wins. The Tories could have used a straightforward FPTP system, but they didn’t: if they had then David Davies, not David Cameron, would have won the 2005 leadership election.

AV is substantially similar to this process of successive ballots but rather than a sequence of ballots, a single ballot is held with voters ranking candidates by preference. In common with the Tory system, the last candidate is eliminated after the first ballot but rather than return to the electorate for another round of voting the second preferences of the people who voted for the loser are inspected and votes redistributed accordingly. This process is repeated until one candidate has more than 50% of the votes.

The Tory leadership election is not identical to AV because the electorate can switch votes between rounds, whilst in an AV election the rankings are chosen and frozen at the time of the first (and only) ballot. With electorates of tens of thousands the Tory leadership system could not be used for parliamentary constituencies without substantially increased cost and time taken to conduct the election, I will assert that it would produce the same result as AV.

These political sophisticates have rejected FPTP as a method of choosing who represents them, why do so many of them not support the same for us?

AV will not bring great changes to our elections, the majority of constituencies would return the same MP under AV as they currently do under FPTP. The benefit of AV over FPTP is that tactical voting, where you attempt to encode your preferences with a single X by second guessing who everyone else will vote for, becomes largely irrelevant.

We are not being given a choice between FPTP and an ideal electoral system, we are not being asked whether AV is a perfect system for voting, we are being given a choice between FPTP and Alternative Vote. Personally I would prefer a system of proportional representation, but that isn’t on offer.

In the absence of a better choice I will vote “Yes to AV”!

*The BBC have apparently banned themselves from describing the choice of AV over FPTP as “reform”

Apr 09 2011

Book Review: The Chemist Who Lost His Head by Vivian Grey

Following on from “The Measure of All Things” my interest in Antoine Lavoisier was roused, so I went off to get a biography: “The Chemist who lost his head: The Story of Antoine Laurent Lavoisier” by Vivian Grey. This turns out to be a slim volume for the younger reader, in fact my copy appears to arrive via the Jenks East Middle School in Tulsa. As a consequence I’ve read it’s 100 or so pages in under 24 hours – that said it seems to me a fine introduction.

Antoine Lavoisier lived 1743-1794. He came from a bourgeoisie family, the son of a lawyer, and originally training as a lawyer. Subsequently he took up an education in a range of sciences. As a young man, in 1768, he bought into the Ferme Générale which was to provide him with a good income but led to his demise during the French Revolution. The Ferme Générale was the system by which the French government collected tax, essentially outsourcing the process to a private company. Taxes were collected from the so-called “Third Estate”, those who were not landed gentry or clergy. Grey indicates that Lavoisier was a benign influence at the Ferme Generale, introducing a system of pensions for farmers and doing research into improved farming methods. Through the company he met his future wife, Marie Anne Pierrette Paulz, daughter to the director of the Ferme – Antoine and Marie married in 1771 when she was 14 and he 28.

Lavoisier started his scientific career with a geological survey of France, which he conducted as an assistant to Jean Etienne Guettard between 1763 and 1767. This work was to be terminated by the King, but was completed by Guettard with Antoine Grimoald Monnet although Lavoisier was not credited. There seems to be some parallel here with William Smith’s geological map of the UK produced in 1815.

Through his geological activities Lavoisier became familiar with the mineral gypsum, found in abundance around Paris. He undertook a detailed study of gypsum which sets the theme for his future chemical research: making careful measurements of the weight of material before and after heating or exposure to water. He discovered that gypsum is hydrated: when heated it gives off water, when the dehydrated powder (now called plaster of Paris) is re-hydrated it forms a hard plaster. He wrote this work up and presented it to the Académie des Sciences – the French equivalent of the Royal Society, on which I have written repeatedly.

He was to present several papers to the Académie before being elected a member of this very elite group at the age of twenty-five, half the age of the next youngest member. Once a member he contributed to many committees advising on things such as street lighting, fire hydrants and other areas of civic interest, the Académie was directly funded by the King and more explicitly tasked with advising the government than the Royal Society was. Lavoisier was also involved in the foundation of the new metric system of measurement, which was the subject of “The Measure of All Things”. Lavoisier became one of four commissioners of gunpowder – an important role at the time. During his life he would have had contact with Joseph Banks – a long term president of the Royal Society, and also Benjamin Franklin – scientist and also United States Ambassador to France.

From a purely scientific point of view Lavoisier is best known for his work in chemistry: his approach of stoichiometry – the precise measurement of the mass of reactants in chemical reactions led to his theory of combustion which ultimately replaced the phlogiston theory. It is this replacement of phlogiston theory with the idea of oxidization that forms the foundation of Kuhn’s “paradigm shift” idea, so Lavoisier has a lot to answer for!

The portrait of Antoine and Marie Laviosier at the top of the page is by Jacques-Louis David painted ca. 1788. It strikes me as quite an intimate portrait with Marie pressed against Antoine, looking directly at the viewer whilst her husband looks at her. Marie played a significant part in the work of Lavoisier, as well as recording experiments and drawing apparatus (something that takes good understanding to do well), and assisting with correspondence and translation she was also responsible for publishing Mémoires de Chimie after his death. She was a skilled scientist in her own right. The equipment on the table and floor can be identified: on the floor is a portable hydrometer and a glass vessel for weighing gases. On the table are a mercury gasometer, and a glass vessel container mercury – likely illustrating the properties of oxygen and nitrogen in air.

Antoine Lavoisier was executed in 1794, for his part in the Ferme Générale. His execution is attributed, at least in part to the ire of Jean-Paul Marat, who Lavoisier had earlier blocked from membership of the Académie des Sciences. It seems Lavoisier had been warned by friends that his life was in danger but appeared to think his membership of the Académie des Sciences would protect him. Ironically Jacques-Louis David also painted “The Death of Marat”.

100 pages on Lavoisier was not enough for me, I’m going for “Lavoisier” by Jean-Pierre Poirier next – some fraction of which appears to be available online, but I’m going for a paper copy.