Author's posts

Dec 22 2010

Christmas Calendar 2010

For the past few years I’ve been making my own calendars, as a Christmas present. As best I can I use photos taken in the stated month. This year half of them are taken by Mrs SomeBeans and half by me.

The cover image – A Caiman Lizard, living at Chester Zoo

January – our house in the snow, and the dark – a small amount of white balance fiddling required to reduce the orange cast from the sodium street lights.

February – ski-ing in Westendorf in the Austrian Tyrol

March – A hellebore, Mrs SomeBeans will have taken this one

April – some sandstone from the Sandstone trail, this will be from close to Frodsham.

May – Allium and a bee, bees are difficult to photo because they move around so much

June – The bark of the Strawberry tree

July – A lilac-breasted roller at Chester Zoo, a photograph from a works day out

August – A building at Trentham Gardens – for some reason this makes me think of India

September – Helenium, Mrs SomeBeans making good use of the macro lens she allowed me to buy!

October – A gilded water-buffalo at Biddulph Grange, every garden needs one

November – Witch hazel leaves taking their autumn colour

December – Frost, fog and weak sun by the Shropshire Union Canal

Dec 19 2010

What’s on the end of the stick?

gt;

Once again I return to science. Lately I’ve been playing with some calculations of the diffusion of one thing into another. This is for work – can’t say what, it’s top secret ;-) I have to admit I’ve rather enjoyed it.

Once again I return to science. Lately I’ve been playing with some calculations of the diffusion of one thing into another. This is for work – can’t say what, it’s top secret ;-) I have to admit I’ve rather enjoyed it.

Diffusion calculations ultimately amount to an accounting exercise: this is true of much of physics. You have a bunch of stuff of some sort, and you want to calculate where your stuff will be at some time in the future. The stuff may be electric fields, magnetic fields, heat, molecules or atoms but the point is that new stuff can only be created or destroyed following simple rules and stuff will only travel from one place to another according to other simple rules. Largely it’s a problem of conservation – the amount of stuff is conserved, if stuff leaves one place it must turn up somewhere else.

For diffusion the stuff is molecules, for the purposes of these particular calculations the stuff is not created or destroyed. In the crudest case diffusion is just driven by different amounts of stuff in different places, this is enough to drive the redistribution of stuff since at the molecular level everything is jiggling around at random. If you start with more stuff in one place than another and jiggle it all around at random ultimately it ends up uniformly distributed.

Things can get a bit more complicated, for example you might be interested in your stuff moving into a different environment where it’s not so happy to be or your stuff might be reactive but this is just a smallish change in the basic rules. You also need to define an appropriate boundary condition – what your stuff was doing at one instant in time.

The rules and boundary conditions are expressed as a set of equations; these may have an analytical solution – that’s to say you can write down a further equation that specifies where everything is and when (which you can make into a pretty picture for the boss). Or you may have to carry out a numerical solution: divide time and space up into little pieces and apply the rules in small steps – this is an inelegant but frequently necessary method which, if done naively, can bite you on the arse. Or more technically: “exhibit undesirable numerical instability”.

It turns out that the analytical solution for my current problem can be found in Crank’s “Mathematics of Diffusion”, and so the main work was in making a story for those less interested in equations. The fundamental rules for diffusion are elegant and beautiful, the solutions for specific cases can be ugly and a bit hairy. This is where my skill comes in, to be honest I’m not that good at maths so I couldn’t solve the equations myself – but given a bit of time I can work out which equation is the solution to my problem and carry out calculations with it.

My original adventures with diffusion started in the mid-nineties whilst I was a postdoctoral researcher at the physics department in Cambridge – I was funded by Nestle to measure water diffusing into starch. They were interested in this because at the time they were making a KitKat icecream, which involved putting damp icecream next to crispy wafer with the entirely predictable outcome: the wafer went soggy even when the icecream was stored at –20oC. I spent 18 months or so doing experiments and calculations to demonstrate the very obvious which was if you want to stop your crispy wafer going soggy the best thing to do is coat it in something lardy and therefore water-repellent – chocolate is good! In the meantime I learnt a wide range of things about diffusion and experiments.

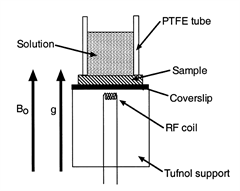

Water diffusing into starch turns out to be a more involved case from a modelling point of view because of the whole “going soggy” thing: basically the properties of the starch change with their water content so there’s feedback between how much water there is and how easy it is for more water to arrive. I did experiments to see where the water was in the starch. This was done using stray-field nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (STRAFI), which required the sample to be stuck on the end of a stick and shoved up the bore of a big magnet, hence the title of this post.

This is another illustration of scientific impact: the core results I relied on for my couple of weeks of calculation date back decades or even hundreds of years. The rules for diffusion were first formulated by Fick in 1855, and since then work has been on-going in solving the equations for ever more complex situations. The 18 months I spent 15 years ago meant that when I returned to it rather then spending several months getting acquainted I could drop pretty much straight in and get some useful results within a couple of weeks. It’s difficult to say what the financial impact for my company might be, with any luck it will save some people at the lab bench a bit of time because results that, are on the face of it, a little odd will have a clear explanation or it may turn out that the calculations show they should stop what they’re doing now because it will never work.

References

- Hopkinson, I., R. A. L. Jones, P. J. McDonald, B. Newling, A. Lecat, and S. Livings. “Water ingress into starch and sucrose : starch systems.” POLYMER 42, no. 11 (May 2001): 4947-4956.

- Hopkinson, I., R. A. L. Jones, S. Black, D. M. Lane, and P. J. McDonald. “Fickian and Case II diffusion of water into amylose: a stray field NMR study.” CARBOHYDRATE POLYMERS 34, no. 1 (December 5, 1997): 39-47.

- Crank, J. “The Mathematics of Diffusion” Oxford Science Publications.

Dec 12 2010

Nevil Maskelyne and Maiden-pap

This post is about Nevil Maskelyne and his 1775 measurements of the Scottish mountain, Schiehallion (know locally at the time as Maiden-pap), made in order to determine the mass of the earth. My interest in this was stimulated by the Gotthard Base Tunnel breakthrough, since the precision of drilling seemed pretty impressive (8cm horizontal, 1cm vertical see here). There’s a technical explanation of the surveying here. You may wonder how these two things are related.

This post is about Nevil Maskelyne and his 1775 measurements of the Scottish mountain, Schiehallion (know locally at the time as Maiden-pap), made in order to determine the mass of the earth. My interest in this was stimulated by the Gotthard Base Tunnel breakthrough, since the precision of drilling seemed pretty impressive (8cm horizontal, 1cm vertical see here). There’s a technical explanation of the surveying here. You may wonder how these two things are related.

It’s all about gravity: gravity is the force exerted by one object on another by virtue of their masses. The force is proportional to the masses of the two objects multiplied together divided by the distance between the centres of the two objects squared. This is Isaac Newton’s great insight, although he only applied it to the orbits of celestial bodies. The mass of an object depends on both its density and its volume.

Maskelyne measured the mass of Schiehallion by looking at the deviation of a plumb line from vertical. The problem for the Gotthard Tunnel is that, if you’re surveying underground, measuring the vertical could be hard because if the density of the rocks around you is different in different directions then a plumb-line will deviate from vertical. Actually it’s probably not a huge problem for the Gotthard Base Tunnel, the deviations Maskelyne measured were equivalent to about 1cm over the 14km length of the Gotthard Base Tunnel sections. Furthermore Maskelyne was looking at an isolated mountain: density of about 2500kgm-3 surrounded by air: density about 1kgm-3, under the Alps the variations in density will be far smaller. So we can relax – density variations probably won’t be an important effect. Although it’s interesting to note that the refraction of light by air is significant in the Gotthard Tunnel survey.

Oddly, Newton didn’t consider Maskelyne’s measurements possible, thinking that the force of gravity was insignificant for objects more mundane than worlds. However he demonstrated that for a largish mountain (3 miles high and 6 miles wide) there would be a deviation of the plumb line from vertical of “2 arc minutes”. Angles are measured in degrees (symbol:o) – there are 360o in a circle. Conventionally, if we wish to refer to fractions of a degree we talk about “minutes of arc”, there are 60 minutes in a degree; or even “seconds of arc” – there are 60 seconds of arc in 1 minute of arc. 1 second of arc is therefore 1/1,129,600th of a circle. At the time of Newton’s writing (1687) this deviation of 2 minutes of arc would have been measurable.

Why is measuring the mass of a mountain a job for the Astronomer Royal, as Nevil Maskelyne was at the time? Measuring how much a plumb line is deflected from the vertical is not simple because normally when we want to find vertical we use a plumb line (crudely a string with a weight at the end). The route out of this problem is to use the stars as a background against which to measure vertical. Maskelyne’s scheme was as follows:

- Find a mountain which stands isolated from it’s neighbours, with a ridge line which runs East-West and is relatively narrow in the North-South direction. This layout makes experiments and their analysis as simple as possible.

- Measure the deviation of a plumb line against a starry background at two points: one to the north of the ridgeline and one to the south (the plumb line will deviate in opposite directions at these two locations).

- Carefully survey the whole area, including the location of the the two points where you measured the plumb line and the size and shape of the mountain.

- Calculate the mass of the mountain from the survey of its size and shape (which gives you it’s volume) and the density of the rocks you find on the surface.

- From the mass of the mountain and the deviation of the plumb line you can work out the density, and therefore mass, of the earth

Measuring the location of stars to the required accuracy is a tricky business since they appear to move as the earth turns and the precision of the required measurement is pretty high. I worked out that using the 3m zenith sector (aka “telescope designed to point straight up”) the difference in pointing direction is about 0.1mm for the two stations – this was measured using a micrometer – essentially a a fine-threaded screw where main turns of the thread only add up to a small amount of progress. The ground survey doesn’t have such stringent requirements, although rather more time was spent on this survey than the stellar measurements.

Reading the 1775 paper that Maskelyne wrote is illuminating: at one point he lists the various gentleman who have visited him at his work! The work was paid for by George III who had provided money to the Royal Society for Maskelyne to measure the “transit of Venus”, some cash was left over from this exercise and the king approved it’s use for weighing the earth.

The value for the density of the earth that Maskelyne measured 235 years ago is about 20% less than the currently accepted value – not bad at all!

References

- The wikipedia article is good, including history and physics of the measurements (equations for those that want): http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schiehallion_experiment

- This presentation to the Royal Philosophical Society in Glasgow in 1990 has a lot of historical background: http://www.sillittopages.co.uk/schie/schie90.html

- Maskelyne’s initial paper “An account of observations made on the mountain Schehallien for finding its attraction” Phil. Trans., 1775, 65, 500-542 is surprisingly readable, and provides details of the experimental measurements. The final analysis of the data was published later.

- Map of Schiehallion on Bing (OS mode): http://bit.ly/g1tufF

Dec 05 2010

27 days to power in May

This is a joint review of the books “22 days in May” by David Laws and “5 days to power” by Rob Wilson on the negotiations to form the Coalition government following the May 2010 General Election. The Laws book is his personal account of those negotiations, and his subsequent brief period in office. The Wilson book is drawn more widely, although he is a Conservative MP. The title of this blog post is a search engine unfriendly mashup of the two titles.

The Liberal Democrats started planning for negotiations in the event of a hung parliament towards the end 2009, this was done secretly by Danny Alexander, David Laws, Chris Huhne and Andrew Stunell on the direction of Nick Clegg. Their consensus, pre-election, was that depending on electoral arithmetic a coalition with Labour or a “confidence and supply” with Tories were the best outcomes for the hung parliament regime where no party had an overall majority. However, Chris Huhne argued that coalition with the Tories was better than “confidence and supply”. Confidence and supply means that the junior party supports the senior for votes of confidence, and for budgetary votes. Huhne argued that under these circumstances LibDems would get all of the blame for difficult government decisions which they supported, without any say over policy. The Tories set up a similar group approximately two weeks before the election comprising William Hague, Ed Llewellyn, George Osborne and Oliver Letwin. Labour apparently did no group planning, their negotiating team comprised Lord’s Mandelson and Adonis (a former LibDem), Ed Balls, Ed Miliband and Harriet Harman. The civil service also seems to have been very well prepared to support negotiations and had a strong preference for coalition over other forms of government. There are strong hints that the civil service were deeply concerned at the prospect of a minority government, or a “confidence and supply” agreement would be bad for confidence in the economy.

The 2010 general election gave the Tories 306 seats, Labour 258, Liberal Democrats 57 and other parties 28 seats (including 8 DUP, 6 SNP, 5 Sinn Fein). This would give a Lib-Lab pact a majority over the Conservatives of 8 seats but with 28 votes with smaller parties so not technically a majority. A Tory-LibDem coalition gives 363 seats, with a majority over Labour of 105. Such a pact can take a rebellion (i.e. MPs of the coalition voting against it) of 35, in theory a Lib-Lab coalition could take no rebellion. In practice the 5 Sinn Fein MPs would likely not vote and the SNP would be unlikely to vote with Tories, except if there was something in it for Scotland.

This electoral maths suggest to me that the only real choice was what form the agreement with the Tories should take: no agreement – likely leading to a new election, “confidence and supply” or full coalition. Coalition with Labour looked really hairy in terms of numbers of seats but there was a lot of enthusiasm in the Liberal Democrats and some enthusiasm in Labour for this. The generation of LibDem MPs who had entered the parliament opposing Tory governments (Paddy Ashdown, Vince Cable, Charles Kennedy, Don Foster etc) were particularly keen. Gordon Brown was keen to form a coalition, and from the Labour team Mandelson and Adonis. Clearly from a negotiating point of view the fact that a coalition with Labour was feasible was a strong card to play.

Steve Richards, in The Independent, prefers to characterise the Coalition agreement between LibDem and Tory as the result of a take over by Orange Book Liberal Democrats, against the will of the party. This seems to misunderstand the internal workings of the party: both the parliamentary party (Commons and Lords) and the federal executive were consulted at the time on how negotiations should progress. They also voted on the outcome, as did the wider membership at a special conference held shortly thereafter. Many of these would be people just like me who would have been nervous of coalition with Tories, and many would have initially preferred coalition with Labour. However, ultimately all of these groups voted emphatically for coalition with the Tories. One striking thing in the whole process was the amount of time the LibDems spent on internal consultation – Labour apparently did none of this, and in the Tory party it was cursory and ad hoc.

Dec 03 2010

This makes me angry

This makes me angry:

Instead nice, gentle Nick Clegg has secured the position of Britain’s most hated man. He has been burnt in effigy by student rioters. Police have told him that he must no longer cycle to work for fear of physical attack. Excrement has been shoved through the letter box of his Sheffield constituency home, from which his family may now have to move for safety reasons.

I can hear the Labour apologists winding themselves up for response already: “Was his family in residence when the shit was pushed through the letter box? Have you got a crime number for that? It’s terrible, but you know he betrayed the people who trusted in him. Moving out of the home is just theatrical.” The president of the National Union of Students, Aaron Porter, Labour party member, decries the “betrayal”, the breaking of a pledge. Anyone like odds on how likely it was that he voted for the Liberal Democrats? Let’s face it: he didn’t, he didn’t vote for the party that he’s excoriating for not implementing the policy he didn’t vote for, the only party to oppose tuition fees. All those Labour folk, talking of the “betrayal”, they didn’t vote against tuition fees either. “Satirical” they say of David Mitchell advocating pissing through Nick Clegg’s letterbox , it isn’t satirical if someone’s actually done it.

As the riots progress an army of armchair revolutionaries bemoan the violence of the police, as buildings are smashed up. “The police should simply keep the protesters moving on, so they don’t cause any trouble”. “The police are stupid”, they say, “I could manage a large crowd of protesters, some intent on violence, much better than them. That’s why I’m sitting here tweeting about it.” “The police van was bait, because every right-thinking person when they see an unattended police van thinks: “Fuck me, I better smash the crap out of that”.”

I used to think it was the Tories who felt power was their divine right but now I know it’s Labour. Len McCluskey, leader of Unite, a Labour affiliated union calls for demos to topple the government, speaking approvingly of the poll tax riots. John McDonnell, Labour MP, says:

I know the Daily Mail will report me again as inciting riots yet again. Well, maybe that is what we are doing.

Beaten in an election, they use weasel words to get people out on the street smashing stuff up. “These cuts aren’t what people voted for, they voted, but they didn’t vote for this. They really meant to vote for Labour, the party who repeatedly reneged on promises to introduce fairer voting. The party who said they were going to reduce the deficit by making cuts, but now only have a blank piece of paper; who can magically make the deficit painlessly go away.”

For the first time in 60 years Liberal Democrats are in government, they are in government at a time when the country faces the largest budget deficit it has had in many decades, it is a crap time to be in government. They are taking hard decisions that Labour would not have the guts to take. For some this is a “betrayal”, they’ll happily contribute to an atmosphere that means a family gets shit pushed through the letterbox of their home, and a columnist in a respected paper can applaud it.

But more than ever before I am proud to say “I agree with Nick”.