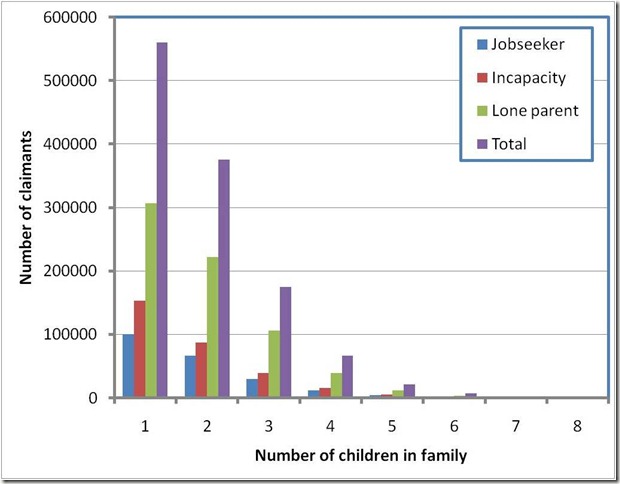

One of this mornings news items is on government plans to limit benefit to a family to the average wage, apparently regardless of the size of the family. This seems to be built around the idea that there are families out there with vast numbers of children who are milking the system to the cost of the rest of us. We can check this idea with numbers. The graph below shows the number of claimants broken down by number of children in the household, the final category is for families containing 8 or more children.

The heights of the columns are a lower bound on the fraction of benefit going to each group, an upper bound would be to multiply each column by the number of children but this would be an over-estimate since benefits don’t increase linearly with number of children. There are a little under 1000 families with 8 children or more. 90% of claimant families have less than four children.

These data tell us nothing about the circumstances of each of the families represented which will include the loss of parents, illness, job loss and all the other small disasters which can befall a family.

The data shown here are from Department of Work and Pensions via The Spectator (here).

Oct 07 2010

Children and numbers

Oct 03 2010

Book review: The History of the Royal Society of London by Thomas Sprat

In which I venture into original material, in the form of Thomas Sprat’s “History of the Royal Society of London, for the improving of Natural Knowledge“. Published in 1667, under the direction of the Royal Society which had first met in 1660, receiving their royal charter in 1662. I must admit to having attempted to read this book a couple of times before and failed; the copy I have is a facsimile of the original therefore written in early modern English with heavy use of the “long s” inevitably leading to an internal voice with a pronounced lisp! It’s probably useful to replace “History” with “Prospectus” in the title, to satisfy modern tastes. Despite it’s age the writing style is surprisingly readable to my modern eyes.

In which I venture into original material, in the form of Thomas Sprat’s “History of the Royal Society of London, for the improving of Natural Knowledge“. Published in 1667, under the direction of the Royal Society which had first met in 1660, receiving their royal charter in 1662. I must admit to having attempted to read this book a couple of times before and failed; the copy I have is a facsimile of the original therefore written in early modern English with heavy use of the “long s” inevitably leading to an internal voice with a pronounced lisp! It’s probably useful to replace “History” with “Prospectus” in the title, to satisfy modern tastes. Despite it’s age the writing style is surprisingly readable to my modern eyes.

Unlike any other book I have read the book starts with a dedication to the King, followed by a poem praising Francis Bacon (1561-1626). Bacon’s presence recurs throughout the book, Sprat clearly sees him as the intellectual godfather of the organisation. The book is divided into three sections; the first is a prehistory describing the state of natural knowledge before the Royal Society, the second section details the founding of the Society and the final section discusses the value of the knowledge the Society seeks.

The tour of prehistory is rapid; starting with the ancient priests who held knowledge to themselves, followed by the Greek philosophers (described as the Ancients) who Sprat feels were too fond of rhetoric in determining questions of knowledge and who he accuses of “hastiness”. The Romans receive relatively short shrift. Following the Roman Empire, Sprat sees the rise of the Church of Rome and a relatively barren period dominated by war, he cites here William of Malmsbury (1080-1143), an early English historian in support of this. He then bemoans the time spent by the Scholastics in what he considers pointless theology in the later period, presumably 1000-1500, William of Ockham falls into this group. Finally he comes to the recent era where he lists five groups involved in natural philosophising. Francis Bacon is cited reverentially once again, those taking on the philosophy of the ancients – tidying it up after it’s release from the abbeys in the Reformation, are less venerated. “Chymists” receive a mixed review with the more pedestrian welcomed but the alchemists, often seeking eternal life or some other fancy, are scorned. Isaac Newton, a later president of the Royal Society was a keen alchemist but by this time it was seen as not quite proper. He also comments on the coming of specialisation to different areas of science.

The founding fathers of the Royal Society started meeting in Doctor Wilkins lodgings in Wadham College, Oxford – it’s not stated explicitly when this started but it ended in around 1638 when the meetings moved to Gresham College in London. Sprat skims over the Civil War (1642-1651), although this period was clearly much on his mind in writing the book, then happily reports: “For the Royal Society had its beginning in the wonderful pacifick year of 1660”, the year of the Restoration when Charles II returned to the English throne. Sprat goes on to describe in some detail the guiding principles of the society, explicitly ruling out a teaching organisation citing the time required to do this and the potentially unhealthy Master-pupil relationship as damaging to the purposes of the Society. It is a principle of the new organisation that men of all religions and nations are welcome. This internationalism is a hallmark of modern science. Also highlighted is the idea that the Royal Society becomes a central repository for written information, the first of its kind. The Royal Society was funded from the subscriptions of it’s fellows, although they were open to public funding.

Sprat then provides a rather detailed description of how the Royal Society is constituted including how they go about their business in terms of doing and reporting experiments, I must admit to finding this a bit dull. It has the air of an organisational fanatic describing his perfect organisation, it’s questionable how closely the Royal Society managed to keep to this ideal. However, in his description of the processes of the Society we can see the genesis of the still used scientific literature, with the primary literature comprised of relatively short papers containing experimental results and theoretical developments based on those results. Charles II makes several appearances here, unsurprising given the recent granting of the Royal charter, but he also seems to have been moderately involved in the Society and had his own chemistry laboratory.

A substantial portion of the middle of the book is taken by a compilation of reports by the early Royal Society, these include:

- Answers returned by Sir Philberto Vernatti (Resident of Batavia in Java Major)

- A Method for making a History of the Weather by Mr Hook

- Directions for the Observations of the Eclipses of the Moon by Mr Rooke

- A Proposal for Making Wine by Dr. Goddard

- A Relation of the Pico Teneriffe

- Experiments of the Weight of Bodies increased in the Fire by Lord Brouncker

- Experiments of a Stone called Oculus Mundi by Dr Goddard

- An account of a Dog dissected by Mr Hook

- Experiments of the Recoiling of Guns by Lord Brouncker

- The History of the Making of Salt-Peter by Mr Henshaw

- The History of Making Gunpowder

- An Apparatus to the History of the Common Practices of Dy[e]ing by Sir William Petty

- The History of the Generation and ordering of Green Oysters Commonly called Colchester-Oysters

I shall write on these reports in a separate post.

The book ends with a lengthy rebuttal of various criticisms of the Royal Society, including how “experimenting” is entirely compatible with the Christian religion and specifically the Church of England; this is perhaps unsurprising given Sprat’s occupation as a churchman. In addition to this there is the appeal that experimental philosophy as demonstrated by the Royal Society can benefit the nation by improving its industry and trade, including such things as importing plants across the emire. It also defends the interest of the nobility in this area, claiming that their country estates are the ideal places to conduct such studies, whilst the lower orders go off to fight wars!

Reading this book was an unusual experience for me. In contrast to the modern histories I more usually read I felt much more obliged to ask questions like: Why is this person writing this book? Why was Bacon so important? Is this some reverence to a politically important forbearer? Why the need for the book at all? A book length defence of such an organisation only 5 years after its formation seems a bit odd.

Reading this has given me a taste for contemporary material, I think I might have to look into Pepys and some original scientific publications.

Further Reading

- Google Books version of the History of the Royal Society of London, for the improving of Natural Knowledge.

- My earlier blog posts on the Royal Society

- Image from the National Portrait Gallery

Oct 01 2010

Regulation and reward

This post is stimulated by an exchange on twitter as to why we are bothered about bankers being paid stacks, whilst seemingly less worried about football players and entertainers being paid similar amounts. This post fails to address that specific question.

Banks are rich because they handle money and take a little charge at each transaction, also they rent out money which attracts few overheads. Footballers and entertainers are rich because wealthy organisations realise that to sell a football team or a film requires a star. Doctors and lawyers are rich because they have rare skills that people are willing to pay well for, the costs of poor legal advice or poor medical advice are loss of wealth or life, respectively, and their lack becomes rapidly obvious.

Pay does not measure a person’s value. Pay measures how much money an employer believes an employee is worth to them, if the employer is also the employee this judgement may be flawed. In some cases this is easy to determine, in other cases it is not. If I look at the company I work in, higher salary goes with greater responsibility for people and greater budgets. In the case of patent attorneys, who are relatively well paid, then it goes with a marketable skill. Scientists doing science are paid acceptably, the company is clear that they are not paid more because there are not local jobs for scientists which pay better.

We’ve recently gone through repeated rounds of “How much are you paid compared to the Prime Minister”, exclusively directed at other public sector workers. This is ridiculous. It’s usually inaccurate as well: the typical figure quoted for the Prime Ministers salary is £142,500; however he will also receive an MP’s salary of £65,738. In addition to this he has use of an apartment in central London at Number 10 and a country house, Chequers. As Tony Blair has demonstrated, the Prime Minister can also expect substantial financial rewards on leaving the position, through speaking fees, directorships and so forth that are based largely on their position of former prime minister (see here and here). The Prime Minister is also entitled to receive half of his salary as pension after he has left office, although Gordon Brown waived this payment.

People make the money they can under the situations they find themselves. I’m sure we’ll all argue that that’s not we’d do personally but let’s assume that we’re all special. Do you own up if you’re under-charged or you receive more change than you deserve or if the electrician offers you a lower price for cash? Viewed in this light the MP’s expenses scandal is nothing unexceptional. Looking at what they were up to I can easily imagine that we’d find exactly the same distribution of abuses if the expenses scheme where I work were regulated in the same way. A whole bunch of people would claim to the limit in an entirely “legal” way; a few would claim less through incompetence in milking the system and a few would act in ways that were basically fraudulent.

What’s the message of this post?

In terms of regulation: don’t rely on the goodwill of man to obtain a favourable societal outcome. Although that might work for some chunk of the population it won’t for a substantial fraction and so the scheme will fail.

Sep 28 2010

Book review: The Map that Changed the World by Simon Winchester

These are some notes on “The Map that changed the World: The Tale of William Smith and The Birth of a Science” by Simon Winchester. It is the story of the creation, by William Smith, of the first geological map of England and Wales, and the first such map on this scale in the world. A geological map shows the distribution of different rock types on the earth’s surface. Sedimentary rocks are laid down in horizontal layers, known as strata, subsequently these layers may be deformed and distorted. Therefore the distribution of rock types on the surface is a slice this distorted underground structure. William Smith’s work went beyond simple mapping the surface by recording what went on under the surface.

These are some notes on “The Map that changed the World: The Tale of William Smith and The Birth of a Science” by Simon Winchester. It is the story of the creation, by William Smith, of the first geological map of England and Wales, and the first such map on this scale in the world. A geological map shows the distribution of different rock types on the earth’s surface. Sedimentary rocks are laid down in horizontal layers, known as strata, subsequently these layers may be deformed and distorted. Therefore the distribution of rock types on the surface is a slice this distorted underground structure. William Smith’s work went beyond simple mapping the surface by recording what went on under the surface.

William Smith was born in 1769, as the industrial revolution was getting under way. Enclosures, coal mining, canal building and drainage work were building blocks to Smith’s maps; as a young man he became involved in surveying as a result of enclosures around his birthplace of Churchill, near Oxford. Following this experience in surveying he became involved in coal mining in Somerset. Here he saw directly the strata beneath the surface and learnt their individual character. Then he was involved in surveying for a canal to link the Somerset coal mines to the main canal system. This combines surveying with geology, since the type of rock the canal goes over determines how easy it is to dig the canal and whether it leaks.

A key insight was that the fossils found within a strata could be used to exactly correlate two distinct outcrops – in the absence of fossils two outcrops might look very similar but actually belong to different strata. Secondly, strata always appeared in the same order: A always comes below B, which comes below C. In places, because subsequent distortion of the rock, this ordering may not be obvious. It was Smith who was responsible for “” which identified the order of strata occurring in England.

Fossils had become collectors items around the time of Smith’s birth. As a result of the increasing awareness of the fossils in the surroundings, sea animals many miles from the sea and fossils with no living counterparts, the biblical account of the creation of the earth was becoming increasingly shaky. In a sense it is geology that brought Darwin to his theory of evolution, the study of rocks makes it increasingly clear that the world is unimaginably old and that in this vast space of time there is room for evolution. In common with Darwin, Smith’s great work was a long time in preparation.

William Smith was dogged by financial problems, he had taken up a mortgage to buy a substantial estate whilst surveying for a canal and was then promptly sacked. Throughout his life he appears to have spent rather enthusiastically, sometimes simply to be seen as having an address in the right place. Ultimately William Smith went to debtor’s prison for a short period in 1819, a few years after his map had first been published. On his release he moved to Yorkshire where he worked on various minor projects in obscurity. He was later returned to the public eye to receive the first Wollaston Medal from the Geological Society of London, along with the recognition he deserved.

Earlier the Geological Society, under the presidency of George Greenough treated Smith shamefully: plagiarising a substantial chunk of his work on the geological map to produce their own version which was published not long after his, at lower cost. Furthermore they refused him admission to the society largely, it seems, on the basis of class. Smith had some previous experience of being plagiarised whilst in working in Bath, by a reverend! Although the subject of class arises a number of times through the book it doesn’t seem to have caused Smith huge impediment, aside from his initial contact with the Geological Society, throughout his life he worked with the landed gentry on various projects and it seems he was valued for this work. In addition he was apparently quite well known to Sir Joseph Banks – long time President of the Royal Society.

It’s striking that in addition to the Royal Society in London, the rest of the country was apparently riddled with philosophical societies, Bath is mentioned in particular in this regard but what really brought it home to me was mention of the Scarborough Philosophical Society, somewhere one wouldn’t now associate with such things.

The book is written in something of a docu-drama style with some sections reading a little like a novel, this is a mixed blessing to my mind – it enhances readability however it always leaves me with the fear that I’m being tricked into believing detail that doesn’t exist. I feel something of a connection to this work; I grew up on the Jurassic coast in Dorset (although this in a time before the marketing term had stuck) and did geology AO level whilst at school. It’s tempting to believe that England was the perfect spot for William Smith to be born: the geology of England is very varied and the industrial revolution provided a perfect excuse for detailed rummaging around in the rocks.

You can see the modern, interactive version of the geological map of Britain here.

Sep 20 2010

Wallpaper paste and the giant death ray

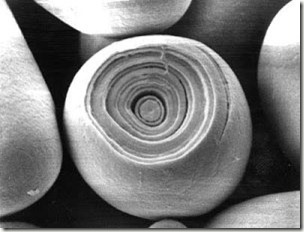

Nature is good a growing fancy structures. It takes air and water and turns them into sugar, a small molecule, which it then stitches together in chains to form starch and these starch chains arrange themselves into starch granules: organised structures with a diameter about that of hair, found in plants. The electron micrograph to the right* shows one that has been eroded to show some of its internal structure.I have my name on a couple of pieces of work on starch. I played a small part in the piece of work described here:

Nature is good a growing fancy structures. It takes air and water and turns them into sugar, a small molecule, which it then stitches together in chains to form starch and these starch chains arrange themselves into starch granules: organised structures with a diameter about that of hair, found in plants. The electron micrograph to the right* shows one that has been eroded to show some of its internal structure.I have my name on a couple of pieces of work on starch. I played a small part in the piece of work described here:

Waigh, T. A., I. Hopkinson, A. M. Donald, M. F. Butler, F. Heidelbach, and C. Riekel. “Analysis of the native structure of starch granules with X-ray microfocus diffraction.” MACROMOLECULES 30, no. 13 (June 30, 1997): 3813-3820. (pdf)

Tom Waigh was a PhD. student in the group I worked in, he was studying starch granule structure. This meant visits to the ESRF in Grenoble; source of mighty x-rays and a micro-focus beam-line, to do experiments. Tom had several days of beam-time, with experiments which essentially required continuous attention (a starch granule in the x-ray beam lasted 15 seconds), therefore a collection of warm bodies were required to press buttons and stuff through the night. Mike Butler and I stayed up late and pressed buttons. Florian Heidelbach and Christian Riekel designed and built the beam-line, and Athene Donald was the boss – supervising Tom’s PhD. and raising money to do the work. Starch granule structure is interesting and funding-worthy for several reasons: we eat lots of starch based things both natural like potatoes and not so natural, like Cheesy Wotsits; it’s used in processing paper and fabric and as a glue. There’s also work going to make plastics from starch, little extruded starch worms can also be found as a replacement for expanded polystyrene packing. Understanding starch granule structure is useful to people who run industrial processes, better knowledge of the granule structure leads to a better understanding of its processing properties which might lead to seeking out or breeding plants, which produce different sorts of starch granule, with different or better properties.There are two types of starch: amylose and amylopectin. Amylose makes shorter, less branched chains, whilst amylopectin makes longer branched chains. Starch granules are onion-like structures with alternating crystalline and amorphous regions. (Crystalline means nicely ordered, amorphous means not nicely ordered). Crystallisation in polymers is one of those puzzling things, how does all that long stringy polymer get folded up into such a nice neat structure. Blind physics is the answer, it’s broadly understandable but when I was active in the field it still wasn’t clear how it got started; once the nucleus of a crystal had formed, its growth was understandable but the formation of the nucleus was not so clear. X-rays tell us about the structure of things on very small length scales, since we’re interested in the variations in structure of an object only 0.1mm across we need to use an x-ray beam much smaller than this. The beam at the ESRF is only 0.002mm across so we can get a very detailed picture of the crystalline and amorphous regions of the starch granule. If you want to find the structure of a car by poking it with a stick, then you need a stick which is much smaller in diameter than the car. All we know of starch granule structure is summarised below:

The experimental procedure was entertaining: the starch granules were deposited on an electron microscope grid – a very fine wire mesh with numbers and letters allowing you to identify where you were on the grid. The starch granules were visible under a low power optical microscope, as were the numbers and letters. The numbers and letters were visible under the harsh stare of the x-ray beam but not the starch granules. So we would print out an optical micrograph, and take it off to the instrument hutch where we would get a shadowograph of the grid from the x-ray beam (sans starch granules). Then there would be a process of half-blind navigation, this was far from leisurely since once the x-ray beam was shining on the starch granule it lasted a few seconds before becoming irreversibly damaged. Once we’d found a starch granule we would take sets of closely spaced scattering patterns in a quest to discover the structure of the crystalline and amorphous bits of the granule. It was like Battleships but rather more sophisticated expensive. To make a microfocus beam line you take the output of a synchrotron – a big wide beam of x-rays and direct it down a cone – known as a capillary. At some point we decided to be cunning and reduce the power of the micro-focused x-ray beam by offsetting the capillary so that the incoming x-ray beam didn’t hit the open end fully. This failed, because it turns out the beam wobbles up and down very slightly. What we should have done was put the attenuators in, but we were a bit tired. These experiments didn’t solve the structure of the starch granule, they filled in another little corner of the big picture. This is how much of science works. The story of the starch granule structure is one of a repeating theme in nature: it can do subtle things with structure without a large machinery to make it happen.

Update: Athene Donald has written on her side of this story -“Am I having impact?” some nice detail on the origins of the work and the problem of impact. *Images from Braukaiser.com