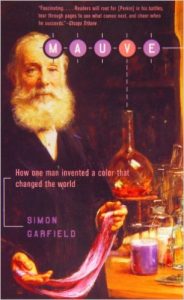

Mauve: How one man invented a color that changed the world by Simon Garfield is a biography of William Perkin. Who first synthesised the aniline dye, mauve, in 1856 at the age of 18.

Mauve: How one man invented a color that changed the world by Simon Garfield is a biography of William Perkin. Who first synthesised the aniline dye, mauve, in 1856 at the age of 18.

Synthetic dyes were to form the catalyst for the modern chemical industry, an area close to my heart since I worked at Unilever on fluorescent and “shader” dyes for the colouring of laundry and teeth. For my undergraduate degree and PhD I was close to organic synthesis labs but didn’t participant with any any enthusiasm (everything gets mixed up and you can poison, burn or explode yourself!).

The book starts with a trip by William Perkin to the United States in 1906, and a series of events to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of his discovery. It’s very reminiscent of similar celebrations on a visit of Lord Kelvin at around the same time. By the later years of his life he was lauded in his field, if not so much beyond it.

Chemistry as a subject was relatively unformed in the middle years of the 19th century. Lavoisier, Davy, Dalton and others had laid the foundations of the modern subject in the early years of the century but it looked nothing like it does today. Chemical formulae were understood but their structural meaning was still a mystery and certainly not liable to routine elucidation. There were chemical industries of sorts, such as the manufacture of gunpowder, the preparation of dyes and tanning. Coal gas was made from coal, producing a variety of by-products including coal tar.

Perkin was studying at the Royal College of Chemistry as an assistant to August Hofmann who was focused on the idea of synthesising quinine from coal tar. He had been encouraged in his scientific studies by Faraday, and Hoffmann had personally intervened with his father for him to study at the Royal College, who had a career in architecture in mind for him.

There is a superficial similarity in the chemical compositions of aniline, a component of coal tar, and quinine. At the time it seemed plausible to synthesis the one from the other. Quinine was highly valued as an antimalarial drug whose supply was very limited. In the end quinine was not to be synthesised until 1944 by Robert Woodward. The synthesis of useful analogues of natural compounds continues to be one of the driving forces in synthetic chemistry.

In 1856, whilst trying to make quinine, Perkin synthesised an attractive colour (mauve) that dyed silk. Such a discovery was not entirely novel or unknown, the colouring properties of coal tar derivatives had been observed before. However, Perkin saw commercial potential and approached a Scottish dye manufacturer, Robert Pullar for advice. At the time dyes such as madder, indigo and cochineal were derived from animal or vegetable matter and were expensive and unpredictable. The natural growth process meant you were never quite sure of the quality of product you were making, or using.

Colouring something is only half the story with dyes, it is also important that the dye sticks to the target and stays there after washing or exposure to light. The techniques and materials for achieving this depends on whether the target is cotton, silk, wool, paper or whatever. With a new class of dyes, new techniques were required. So alongside the colouring material Perkin also provided technical services to help his customers use the dyes he made.

The business was boosted when mauve became a fashionable colour, worn by Queen Victoria. Perkin grew his factory in Greenford, and ultimately sold it when he was 35 for around £100,000 (which appears to be something around £75million in current value). After this he seems to have focused on further research rather than any other commercial venture. His motivation for selling up seemed to be that German companies had become dominant in the production of dye. It was felt that they had better access to trained technical personnel, and their companies were more willing to spend money on research (a complaint still heard today). Then, as now, it was argued that the British were good at inventing but not exploiting.

From dyes the synthetic chemical industries expanded into new areas. In the first instance dyes were useful in themselves in preferentially staining different microscopic structures. It was then discovered that some of them had biological activity, such as methylene blue. And from the aniline dyes were synthesised the antibiotic sulfa drugs and then other, uncoloured medicines.

The synthetic adventure was to continue with synthetic polymers which, in common with mauve, started as an unpromising black sludge at the bottom of a reaction vessel.

The chemical industry in Britain was resuscitated by World War I. Britain found itself dependent on German companies for dyes for military uniforms and precursors to explosives at the onset of war. The strategy, repeated across many industries, was for government to take direct control with the resulting organisations continuing after the war. For the chemical industry this lead to formation of ICI, Imperial Chemical Industries. The manufacture of bulk chemicals has largely moved to China now and ICI broke up and was sold between the early nineties and 2010.

Mauve is an enjoyable read but lacks depth.