My next book follows on from reading Black and British by David Olusoga. It is Precolonial Black Africa by Cheikh Anta Diop. I was looking for an overview of African history from an African perspective. Diop’s relatively short book focuses on West Africa. It turns out he is a very interesting figure in himself, building several political parties, doing research in history as well as physics and chemistry and having a university named after him. Some of his ideas on African history are controversial (you can see the wikipedia page relating to him here).

My next book follows on from reading Black and British by David Olusoga. It is Precolonial Black Africa by Cheikh Anta Diop. I was looking for an overview of African history from an African perspective. Diop’s relatively short book focuses on West Africa. It turns out he is a very interesting figure in himself, building several political parties, doing research in history as well as physics and chemistry and having a university named after him. Some of his ideas on African history are controversial (you can see the wikipedia page relating to him here).

The core of the controversy is two fold, one is his claim that ancient Egyptians were black, and the second is that there is a historical unity in West Africa civilisation with migration from the east of Africa populating the continent. The basis for this thesis relies quite heavily on similarities in totemic names across the region as well as cultural similarities. These days there is some support for the migration of populations out of the Nile basin to West Africa from DNA evidence.

Most of the discussion in this book is oriented around the area of West Africa where Diop grew up, in Senegal, with some mentions of Eygypt and Sudan. Diop draws parallels in the internal organisations across the empires of Ghana, Mossi, Mali and Songhai. The Empire of Ghana stretched beyond the boundaries of the modern country, and stood for 1250 years. Mossi was to the east and south, in the area of modern Burkino Faso, Mali and Songhai were a little to the north encompassing the modern Timbucktu. Looking at wikipedia these empires appear to have overlapped to a degree both in time and space. Precolonial Black Africa covers the period from about 300AD to the 17th century although it does not make much reference to dates.

There is almost no mention even of the area of Nigeria, a little to the east, or Southern Africa. I was nearly half way through the book before I realised that Sudan referred to two different places: Sudan the modern state in North East Africa, and the Sudan Empire which stretches across the southern margin of the Sahara in the West of Africa.

The books starts with a description of the caste system, emphasising the two-way nature of the system and contrasting it to a degree with the caste system in India.

Precolonial Black Africa contrasts Africa with Europe, in the period covered by the book Europe was based on city-states which evolved into feudal structures, with Roman geographical divisions, where defence from marauders by the lord in the castle was important. Land ownership was core of this political system whereas Africa evolved more along Egyptian lines which saw countries divided into regions with regional governance and no tradition of land ownership.

These empires were led by kings with a small cabinet of advisors who had both a regional responsibility and a specialism (like a minister for finance, or the army). Although not republics, nor democratic in the modern Western sense, Diop claims that these governments were more representative than their Western European equivalents of the time.

The technological expertise of the ancient Romans and Greeks was carried through the Middle Ages by the Arab world. It is no coincidence that Spain was once a technology leader, given the Muslim rule of Spain. Islamization of West Africa is a recurring theme of the book, and Arab writers feature regularly in the lists of sources for the early history of Africa. Islam was important in education through to the present day, this is in part responsible for slowed technological progress in the region. Islamic schools did not place a great emphasis on what they consider pagan history, nor so much on modern science.

Precolonial Black Africa covers technology relatively briefly, mentioning architecture and the Great Zimbabwe – a significant stone-built city in present day Zimbabwe whose early excavation was plagued by the then Rhodesian governments view that it could not be constructed by Black Africans. Coins, and metalworking are also mentioned – West Africa made relatively little use of the familiar coinage of European. Gold dust was used as currency, as were Cowrie shells. The Benin Bronzes dating from the 13th century demonstrate there was significant metalworking skill in West Africa (the Bronzes are currently in the news as the UK refuses to return them to Benin). Little of technology and writing seems to have survived from precolonial times, I suspect this is a combination of the environment which is not conducive to the preservation of paper (or even metal), successive colonisations by Islam and then Europeans and relatively little archaeological activity.Trade seemed quite significant across West Africa, even in the absence of conventional coinage.

The interesting thing reading this book is the contrast with flaws that Western history has had in the past, being focussed on great men, the idea of the natural superiority of the white man, and leaning heavily on Classical heritage for legitimacy. I suspect these points of view are generally not prevalent in modern academic history but they certainly hold sway with the current UK government and a coterie of right-wing historians. To a degree Diop suffers the same types of prejudices but from a different perspective – the superiority of the Black African. My view of African history is still heavily influenced by those old Western European foundations.

After a rocky start I came to enjoy this book, I found the book alien in a couple of respects firstly in its discussion of history from an African perspective, and also simply that it is African history. What I know of Africa is largely through a colonial lens.

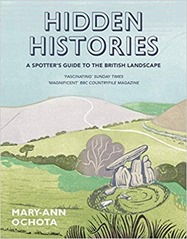

Hidden Histories: A spotter’s guide to the British Landscape

Hidden Histories: A spotter’s guide to the British Landscape