Reading the biography of Isambard Kingdom Brunel got me interested in engineers; Rolt, the author of the Brunel biography, mentioned the biographical writings of Samuel Smiles: in particular his “Lives of the Engineers”. This post is about one part of the full work: ”The Locomotive. George and Robert Stephenson” this edition was published in 1879 although the original was written in the years following George Stephenson’s death, around 1860. The title describes its contents. George Stephenson, although not the inventor of the first locomotive, was instrumental in making it a workable proposition and his son (Robert) continued in his fathers line of work, although died quite young.

Reading the biography of Isambard Kingdom Brunel got me interested in engineers; Rolt, the author of the Brunel biography, mentioned the biographical writings of Samuel Smiles: in particular his “Lives of the Engineers”. This post is about one part of the full work: ”The Locomotive. George and Robert Stephenson” this edition was published in 1879 although the original was written in the years following George Stephenson’s death, around 1860. The title describes its contents. George Stephenson, although not the inventor of the first locomotive, was instrumental in making it a workable proposition and his son (Robert) continued in his fathers line of work, although died quite young.

George Stephenson (1781-1848) was born and grew up around Newcastle-upon Tyne, at the time the area was riddled with coal workings. His father was employed as a fireman working on the pumping engine at Wylam colliery.

George is described as an inquisitive child very interested in nature, and constructing models of the machines he saw around him. He started working with the engines at the colliery as a child progressing to ever more responsible jobs at a range of collieries. Alongside this he did various bits of other work, such as shoe-last making and clock and watch repairs to bring more money in; paying to be taught to read and do arithmetic as he entered his late teens. I can’t help making a parallel with Joseph Banks who benefited from a more prosperous upbringing. It’s worth noting here that Samuel Smiles also wrote a book called “Self-help”, it’s clear he’s very much taken with George Stephenson as a self-made man, he is also very much taken with the entirely private nature of the enterprises he undertook.

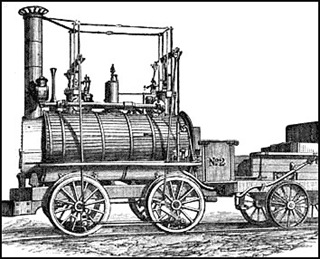

Steam engines had been used to pump water out of mineworkings since around 1710 with the invention of the steam engine by Thomas Newcomen. These were large, inefficient engines. The first attempts at making a traveling engine seemed to take place around 1769 by Cugnot in France with the first practical moving steam engines due to Richard Trevithick around the turn of the century (1800). In the meantime various miner owners were experimenting with modified roadways to ease the movement of large amounts of heavy stuff (ores, coal) from mine-head to waterway for onward transport. This started with the laying down of wooden roads, followed by metal plates (1738) and finally rails (1776). It’s intriguing to see how the coalescence of these elements around mineworkings led naturally to the invention of the locomotive. For the early railroads, such as the Manchester-Liverpool there was a very real question as to whether locomotives or horses should be used as moving force.

The Manchester-Liverpool line really is key here: it was built out of desperate need for better commercial communication between Liverpool (port) and Manchester (manufacturing centre). In common with many lines there was enormous opposition on the ground from landowners and canal owners. It is also here that the modern locomotive comes into being in the form of the “Rocket”, reliability and commercial viability being absolutely key. In common with Brunel, Stephenson also faced parliamentary committees scrutinising the appropriate railway bill. In early discussions Stephenson argued that the locomotives would not exceed a speed of 12 miles an hour, so as not to scare the parliamentarians. Early railway lines were built with goods in mind, but turned out to be immensely, surprisingly popular for the carrying of passengers. The alternative being slower, less comfortable horse-drawn carriages of much lower capacity. George Stephenson was also responsible for at least some of the initial surveying of routes.

The rate at which the rail network came into being is truly astounding. The Manchester–Liverpool was opened in late 1830 by 1843 there were lines linking London to Birmingham, Southampton, Bristol, Brighton and Dover. There were also lines from Liverpool to Manchester and Leeds and onwards to York and Middlesborough, there was also a line between Newcastle and Carlisle. Follow this there was a wild burst of speculative activity, with several hundred proposals to parliament for new lines in 1845 (maps here).

Also covered in this book is Robert Stephenson (1803-1859), George Stephenson’s son. George gave Robert the education that he wished for himself. Although Robert started his engineering career working in the Stephensons’ locomotive workshop, set up in Newcastle, prior to the building of the Manchester-Liverpool he went on to be involved in the surveying and planning of new railway lines. Most notably bridges such as the Britannia Bridge across the Menai Straits, the Victoria Bridge across the Lawrence Seaway and the High Level Bridge in Newcastle. These first two were both originally “tube” design but were modified in the case of the Victoria bridge to a trestle design and the Britannia bridge was destroyed by fire in 1970. The building of the railways necessitated a huge expansion in bridge building: big, strong, well-built bridges.

Overall an enjoyable read although I suspect Samuel Smiles does not comply with modern historical best practice, with his enthusiasm for self-help, and anecdotes shining through in a number of places. Nevertheless, I feel motivated to read some more of his biographical work of the engineers of the 18th and 19th century.

References

Full text of a number of Samuel Smiles books available here.