This is a review of  Data Strategy by Bernard Marr. The proposition of the book is that all businesses are now data businesses and that they should have a strategy to exploit data. He envisages such a strategy operating through a Chief Data Officer and thus at the highest level of a company.

Data Strategy by Bernard Marr. The proposition of the book is that all businesses are now data businesses and that they should have a strategy to exploit data. He envisages such a strategy operating through a Chief Data Officer and thus at the highest level of a company.

It is in the nature of things that to be successful you feel that you have to be saying something new and interesting. The hook for this book is big data, or the increasing availability of data, is a new and revolutionary thing. To be honest, I don’t really buy this but once we’re over the hook the advice contained within is rather good.

Marr sees data benefitting businesses in three ways, and covers these in successive chapters:

- It can support business decisions – that’s to say helping humans make decisions;

- It can support business operations – this is more the automated use of data, for example, a recommender algorithm you might come across at any number of retail sites is driven by data and falls into this category;

- It can be an asset in its own right;

This first benefit of supporting business decisions is further sub-divided into data about the following:

- Customers, markets and competition

- Finance

- Internal operations

- People

The chapter on supporting business operations contains quite a lot of material on using sensors in manufacturing and warehouse operations but also includes fraud detection.

Subsequent chapters cover how to source and collect data, provide the human and physical infrastructure to draw meaning from it and some comments on data governance. In Europe this last topic has been the subject of enormous activity over the past couple of years with the introduction of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) which determines the way in which personal information can be collected and processed.

Following the theme of big data, Marr’s view is that the the past is represented by data in SQL tables whilst the future is in unstructured data sources.

My background is as a physical scientist, and as such I read this with a somewhat quizzical “You’re not doing this already” face. Pretty much the whole point of a physical scientist is to collect data to better understand the world. The physical sciences have never really had a big data moment, typically we have collected and analysed data to the limit of currently available technology but that has never been the thing itself. Philosophically physical sciences gave up on collecting “all of the data” long ago. One of the unappreciated features of the big detectors a CERN is their ability to throw away enormous quantities of data really fast. If you have what is a effectively a building sized CCD camera then it is the only strategy that works. This isn’t to say the physical sciences always do it right, or that they are directly relevant to businesses. Physical sciences work on the basis that there are universally applicable, immutable physical laws which data is used to establish. This is not true of businesses, what works for one business need not work for another, what works now need not work in the future.

Reading the book I kept thinking of A computer called Leo by Georgina Ferry, which describes the computer built by the J. Lyons company (who ran a teashop and catering business) in the 1950s. Lyons had been doing large scale data work since the 1920s, in the aftermath of the Second World War they turned to automated, electronic computation. From my review I see that Charles Babbage wrote about the subject in 1832 although he was writing more about prospects for the future. IBM started its growth in computing machinery in the late 19th century. So the idea of data being core to a business is by no means new.

The text is littered with examples of data collection for business good across a wide range of sectors. The Rolls-Royce’s engine monitoring programme is one of my favourites, their engines send data back to Rolls-Royce four times during each flight. This can be used to support engine servicing, and, I would imagine, product development. In the category of monetizing data American Express and Axciom are mentioned, they provide either personal or aggregate demographic information which can be used for targeted marketing.

Some entries might be a bit surprising, restaurant chains in the form of Dominos and Dickey’s Barbeque Pit are big users of data. Walmart also makes an appearance. This shouldn’t be surprising since the importance of data is a matter more of business scale than sector, as the Lyons company shows.

Marr repeatedly tells us that we should collect the data which answers our questions rather than just trying to collect all the data. I don’t think this can be repeated too often! It seems that many businesses have been sold (or built) Big Data infrastructure and only really started to think about how they would extract business value from the data collected once this has been done.

Definitely thought provoking, and a well-structured guide as to how data can benefit your company.

Chrysalis: Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis

Chrysalis: Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis Nabakov’s Favourite word is Mauve by Ben Blatt

Nabakov’s Favourite word is Mauve by Ben Blatt

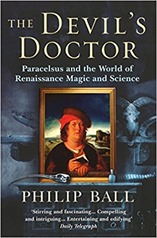

The Devil’s Doctor

The Devil’s Doctor