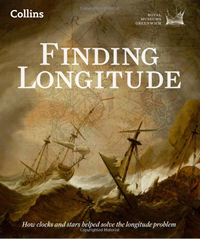

Much of my reading comes via twitter in the form of recommendations from historians of science, in this case I am reading a book co-authored by one of those historians: Finding Longitude by Richard Dunn (@lordoflongitude) and Rebekah Higgitt (@beckyfh).

Much of my reading comes via twitter in the form of recommendations from historians of science, in this case I am reading a book co-authored by one of those historians: Finding Longitude by Richard Dunn (@lordoflongitude) and Rebekah Higgitt (@beckyfh).

I must admit I held off buying Finding Longitude for a while since it appeared to be an exhibition brochure, maybe not so good if you haven’t attended the exhibition. It turns out to be freestanding and perfectly formed.This is definitely the most sumptuous book I’ve bought in quite some time, I’m glad I got the hardcover version rather than the Kindle edition.

The many photographs throughout the book are absolutely gorgeous, they are of the instruments and clocks, the log books, artwork from the time. You can get a flavour from the images online here.

To give some context to the book, knowing your location on earth is a matter of determining two parameters: latitude and longitude:

- latitude is your location in the North-South direction between the equator and either of the earth’s poles, it is easily determined by the height of the sun or stars above the horizon, and we shall speak no more of it here.

- longitude is the second piece of information required to specify ones position on the surface of the earth and is a measure your location East-West relative to the Greenwich meridian. The earth turns at a fixed rate and as it does the sun appears to move through the sky. You can use this behaviour to fix a local noon time: the time at which the sun reaches the highest point in the sky. If, when you measure your local noon, you can also determine what time it is at some reference point Greenwich, for example, then you can find your longitude from the difference between the two times.

Knowing where you are on earth by measurement of these parameters is particularly important for sailors engaged in long distance trade or fighting. It has therefore long been an interest of governments.

The British were a bit late to the party in prizes for determining the longitude, the first of them had been offered by Phillip II of Spain in 1567 and there had been activity in the area since then, primarily amongst the Spanish and Dutch. Towards the end of the 17th century the British and French get in on the act, starting with the formation of the Royal Society and Académie des sciences respectively.

One stimulus for the creation of a British prize for determining the longitude was the deaths of 1600 British sailors from Admiral Sir Cloudsley Shovell’s fleet off the Isles of Scilly in 1707. They died on the rocks off the Isles of Scilly in a storm, as a result of not knowing where they were until it was too late. As an aside, the surviving log books from Shovell’s fleet showed that for the latitude (i.e. the easier thing to measure), measurements of the sun gave a 25 mile spread, and those from dead reckoning a 75 mile spread in location.

The Longitude Act was signed into law in 1714, it offered a prize of £20,000 to whoever produced a practicable method for determining the longitude at sea. There was something of the air that it was a problem about to be solved. The Board of Longitude was to judge the prize. The known competitor techniques at the time were timekeeping by mechanical means, two astronomical methods (the lunar distance method, and the satellites of Jupiter) and dead-reckoning. In fact these techniques are used in combination, mechanical timekeepers are simpler to use than the astronomical methods but mechanical timekeepers needed checking against the astronomical gold standard which was the only way to reset a stopped clock. Dead-reckoning (finding your location by knowing how fast you’d gone in what direction) was quick and simple, and worked in all weathers. Even with a mechanical timekeeper astronomical observations were required to measure the “local” time, and that didn’t work in thick cloud.

There’s no point in sailors knowing exactly where they were if maps did not describe exactly where the places where they were going, or trying to avoid. Furthermore, the lunar distance method of finding longitude required detailed tables of astronomical data which needed updating regularly. So alongside the activities of the longitude projectors, the state mechanisms for compiling charts and making astronomical tables were built up.

John Harrison and his timepieces are the most famous part of the longitude story. Harrison produced a series of clocks and watches from 1730 and 1760, in return he received moderate funding over the period from the Board of Longitude, you can see the payment record in this blog post here. Harrison felt hard done by since his final watches met the required precision but the Board of Longitude were reluctant to pay the full prize. Although meeting the technical specification in terms of their precision were far from a solution. Despite his (begrudging) efforts, they could not be reliably reproduced even by the most talented clock makers.

After Harrison’s final award several others made clocks based on his designs, these were tested in a variety of expeditions in the latter half of the 18th century (such as Cook’s to Tahiti in 1769). The naval expedition including hydrographers, astronomers, naturalists and artists became something of a craze (see also Darwin’s trip on the Beagle). As well as clocks, men such as Jesse Ramsden were mass producing improved instruments for navigational measurements, such as octants and sextants.

The use of chronometers to determine the longitude was not fully embedded into the Royal Navy until into the 19th century with the East Indian Company running a little ahead of them by having chronometers throughout their fleet by 1810.

Finding Longitude is a a good illustration of providing the full context for the adoption of a technology. It’s the most beautiful book I’ve read in while, and it doesn’t stint on detail.

The Shock of the Old

The Shock of the Old