Author's posts

Oct 06 2011

Ada Lovelace Day

The 7th October is Ada Lovelace Day, Finding Ada has encouraged me to write a timely post about women in science, technology engineering or mathematics (STEM), specifically it says:

Create content about a woman in STEM that you admire

Ada Lovelace lived 1815-1852, and is sometimes credited as the world’s first programmer for the notes she wrote on Charles Babbages’ analytical engine – a mechanical computing device which was never constructed. She is commemorated in the Ada programming language, developed for the US Department of Defence with reliability in mind.

To be honest I’ve never found scientific inspiration in long dead “heroic” individual scientists. Lately I’ve been reading rather more of the history of science; institutionally the position of women in science until at least the middle of the 20th century was pretty dire: the Royal Society, proud of its internationalism, religious and political intolerance did not admit its first female members until 1945. The first women were admitted to study at Oxford and Cambridge universities in the later half of the 19th century and they did not gain equal formal status with men until the middle of the 20th century. It’s always somewhat bemusing to hear criticisms of other country’s poor record on female education when we weren’t doing so well within living memory.

This is not to say there are no women in the history of science, just that they fitted into the social accepted roles of their times. For example, Marie-Anne Pierette Paulze, the wife of Antoine Lavoisier was clearly heavily and expertly involved in the conduct of his scientific experiments in the late 18th century. William’s sister, Caroline Herschel spent many evenings observing the heavens with him (and by herself), discovering several comets and being formally recognised for her work in her later years with medals from the Royal Astronomical Society (1828) and the king of Prussia (1846). In the late 17th century naturalist and artist Maria Sybilla Merian published several books based around her observations, particularly on the metamorphosis of butterflies, and drawings of flowers and insects both in Europe. Later in her life she spent two years in Surinam where she made a study of South American flora and fauna. I’m rather impressed with Merian, travelling and living in South America in the 17th century was pretty challenging stuff regardless of gender.

Sadly I had not got into the habit of posting on my book reading when I read a biography of Marie Curie: with Nobel Prizes in both physics and chemistry, she is outstanding even ignoring the challenges of doing science as a woman at the beginning of the 20th century.

Practically speaking I have been taught science along with many other subjects by women; Ms Pitman who taught me physics (and was sarcastic about the PE teachers), and Mrs Haas who taught me biology. This is not to ignore those whose names I can’t recall, my recall of anything dating back 25 years or so is vague these days! Looking back it seems women made their first impact in science in communication and teaching, see for example Mary Somerville and Émilie du Châtelet.

For me my education, my wonder, was as much to do with my family as my teachers.

Ultimately the woman in STEM who has most influenced me is my mum. She learnt to program on an Elliot 503 in the early sixties: 400 square feet of computer with substantially less processor power than the most lowly of today’s devices. She was later to work for the UK Atomic Energy Authority where she worked on PACE analogue computers, and mechanical calculators. All this is somewhat vague on my part because it is only now I have started to pay an interest in the day to day work she did before I was born.

Forty-one years ago my mum gave up her career when she became pregnant with me and even a few years later, when my brother and I had both started at school, a local employer refused to give her a job application form on the grounds that she was a mother.

As The Inelegant Gardener and I await our first child things are very different.

Oct 01 2011

British Wars–presented in fancy Javascript timeline format

Working my way through various bits of scientific history it becomes clear that what is going on outside the lab can have a profound impact on the protagonists. For the early years of the Royal Society the English Civil War and the Restoration had a big impact on the Fellows; the general feeling was “never again” and there was a search for stability and order. Later, in the 18th century, the American War of Independence and the subsequent wars arising from the French Revolution had an impact on The Lunar Men, impacting as it did on trade and their own radical politics. Lavoisier was to find the French Revolution terminal. In the 20th century, scientists were to play a large role in the Second World War; in codebreaking, radar and in building the atomic bomb. This followed a lesser role in the First World War, developing chemical weapons.

As someone whose formal education in history ended at the age of fourteen I thought I should get a feel for the wars going on around the people closer to my interests; this also seemed to be a good opportunity to play with whizzy Javascript timeline technology courtesy of Simile. It turns out the tricky bit is getting Javascript to run inside WordPress, I cheated a little by simply installing the Simile timeline plugin which fixed things in a way I don’t pretend to understand.

The timeline below is derived from a page in wikipedia entitled British Wars, I wanted to go back to the beginning of the 17th century so I supplemented that list with the linked “List of wars involving England”; Great Britain did not exist prior to the Acts of Union in 1707. You can slide the timeline backwards and forth by dragging it with the mouse.

Javascript timeline broken on upgrade to WordPress 3.5, you can see it here now.

I’ve colour coded the wars geographically as follows civil war: blue, Africa: brown, European:green, Americas:red, India:olive, SE Asia:black, New Zealand:purple and Middle East:orange, I have done this slightly erratically. During the 19th century we appear to have engaged in an awful lot of colonial conflicts around the world.

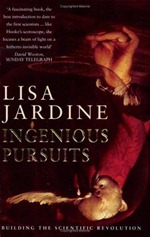

Developing this timeline I have experienced some of the shortcomings of the timeline presentation, I started off with the Cast of Characters in Lisa Jardine’s “Ingenious Pursuits”, entering their birth and death dates, but quickly found I had a rather ugly pile of people whose lives centred around 1680 with outliers before and after that time. Once I started on “British Wars” a second drawback becomes apparent: what is important and what isn’t? In a sense I gave up this decision to the compilers of the Wikipedia page, blindly adding all they had put in. This means the Cod Wars appears alongside the First World War implying some sort of equivalence. They also rate “The Troubles” in Northern Ireland as a war which I struggle to admit.

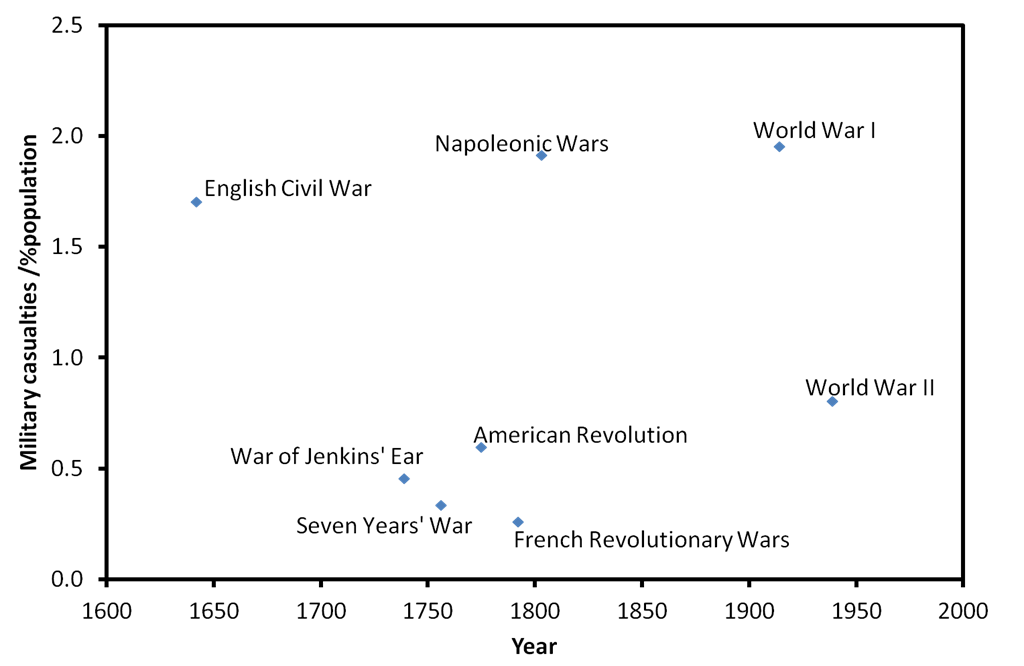

As a second exercise I tried working out how “important” a war was through numbers of military casualties, for this exercise the full list of British Wars is a bit long so again I left the deciding what was important to someone else, in this case a BBC History timeline, this finds a more manageable 10 major wars over the last 400 years or so. In fact it turns out that the Crimean and Boer Wars had relatively few military causalities, so I have omitted them. Below you can see the number of causalities for each war, expressed as a fraction of the population at that time. The casualty figures come from a combination of Wikipedia and Necrometrics, the population figures from the Historical Atlas.

This plot lumps together a whole sequence of conflicts from the first plot into “Napoleonic Wars”. I’ve always known that World War I was known as the war to end all wars, that the casualty figures were horrific, but hadn’t appreciated that the Napoleonic Wars were similar in scale compared to the size of the population. Similarly the English Civil War scores highly for casualties but even so is under-represented in this plot since I decided to use the military casualty figures rather than total deaths relating to the war i.e. including civilians and those who died of disease or famine.

This is a rather parochial view but it has got the sequence of wars Britain has undertaken into some sort of chronology for me.

Sep 25 2011

“Too much, too young”

Ed Miliband has decided to open the Labour conference with a policy! A policy to reduce the cap on tuition fees from £6000 to £9000, you can read all about it here, in the Observer. I wrote on my feelings on tuition fees back here.Miliband’s is a somewhat surprising move; Liberal Democrats battered by this issue, will be bemused to discover that all that ire could have been deflected by the simple expedient of only doubling the tuition fee cap, rather than tripling it. The BBC has helpfully been starting their reporting of this issue with the words “Labour, who introduced tuition fees and then tripled the cap…”.

The policy is to be paid for by not cutting corporation tax on banks, as it will be for all other companies, and by increasing the interest on the student loans for those earning more than Miliband believes his supporters will earn.

The policy odd for a couple of reasons:

- Is this seriously the most important policy area to address? I’d have thought ideas on “going for growth” would be far more important. Or maybe undoing one of those many “attacks” on vulnerable groups.

- It really doesn’t represent a change in principle to the policy being implemented now, just a fiddling with the cap.

- It’s quite transparently another attempt at a political kick at the Liberal Democrats.

My personal opinion on “going for growth” is that there is relatively little government can do to boost growth in the medium term, it can spend in the short term to produce a transient increase but with a deficit as high as ours then is this really a good idea? If we could reliably produce growth by policy, then don’t you think we might be a tiny bit better at predicting growth given known policy? As it stands predicts of GDP growth by pretty much anyone are about as good as could be expected by a monkey throwing sticks at a board.

To me the big problem for Labour is the quote later in the article:

He [Ed Miliband] insisted he would stick to his central message that the coalition is cutting too far and too fast, without providing more detail of where Labour would withhold funding.

An observer would be entirely justified in thinking that Labour’s policy is for no cuts, and tax-raising solely on banks and the unfeasible wealthy, both ultimately rather small sources of income even if you jack up rates to very high levels. Given this, and the “revelations” that the Labour top team fought like ferrets in a sack over deficit reduction before leaving power it is unsurprising that they have little economic credibility.

Sep 22 2011

Book review: Ingenious Pursuits by Lisa Jardine

““Ingenious Pursuits” by Lisa Jardine is the second book I have recently recovered from my shelves, first read long ago – the first being “The Lunar Men”. The book covers the late 17th and early 18th century, and is centred around members of the Royal Society in London but branching out from this group. It is divided thematically, with segues between each chapter.

““Ingenious Pursuits” by Lisa Jardine is the second book I have recently recovered from my shelves, first read long ago – the first being “The Lunar Men”. The book covers the late 17th and early 18th century, and is centred around members of the Royal Society in London but branching out from this group. It is divided thematically, with segues between each chapter.

My edition is illustrated with Joseph Wright of Derby’s “An experiment on a bird in the air pump”, painted in 1768. As a developing historical pedant this mismatch in dates has been irritating me!

The book opens with a chapter on Isaac Newton, the first Astronomer Royal John Flamsteed, Edmond Halley and the comet which would eventually take Halley’s name. It’s also an early example of an argument over “open data”, Flamsteed was exceedingly reluctant to give “his” data on the motions of planets to Newton to use in his calculations. Halley is pivotal in this, not so much through the scientific work he did, but through his work as a conduit between the prickly Newton and Flamsteed.

Robert Hooke features strongly in the second chapter alongside Robert Boyle; Hooke had originally been the wealthy Boyle’s pet experimenter – in particular he was operator for the “air pump”, a temperamental device for evacuating a glass vessel. The early Royal Society recognising his skills, persuaded Boyle to allow them to take him on as Curator of Experiments for the Society. Hooke was also involved with Christopher Wren in surveying London after The Great Fire, and designing many of the new buildings. In fact they also designed buildings with one eye to fitting experiments into them, particularly ones requiring a long uninterrupted drop. One sometimes gets the impression of a highly industrious Hooke implementing the vague imaginings of a series of aristocratic Society members. The constant battles with temperamental equipment will ring a bell with many a modern scientist. Robert Hooke is a central character throughout the book, Lisa Jardine has written a biography of him.

Hooke was also responsible for Micrographia a beautiful volume of images observed principally through a microscope, of insects and plants. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch civil servant and microscopist also supplied his microscopic observations to the Royal Society. It’s interesting that both Leeuwenhoek and later Jan Swammerdam, both based in the Netherlands, were very keen to communicate their results to the Royal Society in London. Interactions with the academiciens in Paris were more formal with another Dutchman, Christian Huygens, a central figure in the French group. Scientific discovery was already a highly international operation.

This was a period in which serious large scale surveying was first undertaken, the French started their great national survey under Cassini. The British, under the direction of Sir Jonas Moore, set up the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, where Flamsteed was employed. Timekeeping was a part of this surveying operation. Finding the latitude, how far you are between equator and pole, is relatively straightforward; finding your longitude – where you are East-West direction is far more difficult. One strategy is to use time: the earth turns at a fixed rate and as it does the sun appears to move through the sky. You can use this behaviour to fix a local noon time: the time at which the sun reaches the highest point in the sky. If, when you measure your local noon, you can also determine what time it is at some reference point Greenwich, for example, then you can find your longitude from the difference between the two times.

To establish the time at your reference point you can either use the heavens as a clock, one method is the timing of the eclipses of the inner moon of Jupiter (Io with a period of 1.8 days), or you can use a mechanical clock. In fact it’s from observations of these eclipses that the first experimental indications of a finite speed of light were identified by Ole Rømer. In the late 17th century the mechanical clock route was starting to become plausible: the requirement is to construct a timepiece which keeps accurate time over long sea journeys, at the equator (the worst case) a degree of longitude is 60 nautical miles and is equivalent to 4 minutes in time. Christian Huygens and Robert Hooke were both producing advances in horology, and would be in (acrimonious) dispute over the invention of the spring driven clock for some time. Huygens’ introduction of the pendulum clock in 1656 produced a huge improvement in accuracy, from around 15 minutes in a day to 15 seconds following further refinement of the original mechanism.

Ultimately the mechanical clock method would win out but only in the second half of the 18th century.This astronomical navigation work was immensely important to nations such as Britain, French and the Netherlands who would even collaborate over measurements in periods when they were pretty much at war. Astronomy wasn’t funded for “wow” it was funded for “where”.

Also during this period there was a growing enthusiasm for collecting things. At the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, Hendrik Adriaan Van Reede was to start adding more native plants to the local botanic garden on behalf of the Dutch East India Company. The Dutch built their commercial horticulture tradition in this period. In France, botany was only second to astronomy in the money it received from the Academie des Sciences. Again, plants were not collected for fun but for trade. In England Sir Hans Sloane was to start collecting; bringing chocolate back from the West Indies, which he marketed as milk chocolate, popular alongside another exotic botanical product: coffee. He was also to bring back the embalmed body of his employer for the trip, the Duke of Albemarle. Sloane was to continue collecting throughout his life, absorbing the collections of others by purchase or bequest – his collection was to go on to form the foundation of the British Museum collection. In Oxford Elias Ashmole, of Ashmolean Museum fame, was to acquire the collection of the planthunter John Tradescant under rather murky circumstances. The collectors of the time were somewhat indiscriminate and not particularly skilled at organising their rather personally driven collections. In their defence though there was no good taxonomy at the time so raw collecting was a start.

The final thematic chapter is largely about medicine, at the time medicine was in a pretty woeful state. Over the preceding years advances had been made in describing the structure of the human body and William Harvey had identified a function: the circulation of blood. However fixing it when it went wrong was not a strength at that time: surgeons “cutting for the stone” were becoming quite agile but there were few reliable drugs and a wide range of positively unhelpful practices.

The book finishes with an epilogue drawing parallels between the discovery of the structure of DNA, and the intense personal story around it, with the interactions between the people discussed previously at the heart of this book. There is also a “Cast of Characters” which provides a handy overview of the book (should I forget its contents again). Compared to The Lunar Men it is an easier read perhaps because it is more discursive around themes rather than providing great detail.

Footnote

My Evernotes on this book are here

Sep 17 2011

Photographing Chester

I’ve lived in Chester for 7 years but realised recently I have scarcely any photos of the city, so a few weeks ago I went off on a morning of indiscriminate photography using a Canon EF-S 10-22mm f3.5-4.5 on my Canon 400D. You can see the results of my labours on this and an earlier trip here.

The 10-22mm lens is a nice, very wide-angle lens but as you can see below it can produce some odd effects when used close-up to take picture of buildings. This can be seen in the picture of Chester Library shown below:

The library is housed in the old Westminster Coach and Motor Car Works, built around 1913-14 with a rather nice brick and terracotta front (see history here).

Aside from my usual problem of apparently having one leg shorter than the other, the verticals in the building converge. The “short-leg” problem can be fixed using Picasa, the aesthetic problem of converging verticals needs a different approach.

It’s worth pointing out that the image shown above is “correct” in the sense that the vertical lines of the building should converge because the top of the building is further away from the photographer than the bottom of the building. This problem is more severe when using a wide-angle lens. I want something that looks like the image below; what’s sometimes known as an “architectural projection”.

In the old days an architectural projection could be achieved using tilt-shift lenses or rather odd darkroom techniques. By the way, Cambridge in Colour, linked to for tilt-shift above is my first port of call for the mechanics of all manner of photographic things.

These days perspective corrections of this sort can be achieved using software, such as Hugin. Hugin is designed as a photostitching software but as a side-effect of this it needs to have all manner “projective geometry” knowledge. Projective geometry relates the real, 3D world to what will appear in a camera (a 2D projection of that world); it’s important in machine vision applications, computer graphics and in this sort of image processing.

The process of “correcting” converging verticals is described in a very good tutorial on the Hugin website. There is also a related perspective correction tutorial, this stops both horizontal and vertical lines from converging, this can have the effect of shifting you from an oblique view to a square on view (sort of). Applying this to my original image of the library we get this:

Which I find rather pleasing. This is Chester Town Hall, built in 1869, similarly treated:

Finally, the Blue Coat “Hospital” which was never a hospital but actually a school, it’s also a demonstration of the perspective correction pushed a little too far, something odd is going on with the dome tower. This is because the things I am applying a warp to are not all in the same plane.

It’s easy to grow familiar with a place, not realising it is a little bit special. Chester really is architecturally special although it’s at times like this I wish there was a filter for modern signage and vehicles. There are a number of black and white “timber framed” buildings, often these are “mock” dating back to the late 19th century:

Whilst others are genuinely old, such as the Bear and Billet Inn built in 1664:

Whilst others are genuinely old, such as the Bear and Billet Inn built in 1664:

The Three Old Arches is reputedly the oldest shop front in England:

And there are all manner of interesting little twiddly bits, I keep spotting more of these each time I visit now:

A load more of my photos of Chester here.

|

| Chester |