Author's posts

Feb 07 2011

Hinterglemm

|

| A view up the Saalbach-Hinterglemm valley, Hinterglemm is in the distance |

Mrs SomeBeans and I have been skiing again, staying in Hinterglemm in the SkiCircus area of Austria. Hinterglemm is the upper of the two main villages in a valley running east-west, Saalbach is the larger village and gets more sun but the lifts are spread out around the village. We went with Inghams, flying from Manchester to Salzburg, the transfer time is about 2 hours, with a stops at Zell am See and Saalbach which are both relatively close. Salzburg airport can’t really cope with the number of package tour flights it gets in a short period.

Conditions last week were fantastic, for the first four days of our holiday we didn’t see a single cloud, temperatures were fairly low but there was no new snow during the week. Skiing was best between about 8:30am-10am before most people, other than the locals, had got out on the slopes. I suspect getting up at 7:30 every morning is not most people’s idea of a holiday.

Hinterglemm has a lot of lift capacity out of the village, a short gondola ride takes you to a set of four chairlifts on the south-facing side of the valley and two longer gondolas take you to summits on the north facing side of the valley. The link to Saalbach on the south side of the valley is a bit odd: from Saalbach it an an old 3-seater chair lift, followed by a long t-bar drag lift and an old 2-seater chair lift. The return from Hinterglemm the link is a bit easier but still involves a short t-bar. A nice range of skiing with some big wide pistes, pistes through trees and a few long black runs on the north-facing side of the valley which we didn’t try out. The area is pretty well linked up with some circular routes, and the ability to get to pretty much anywhere in the linked are in a couple of hours at most.

We stayed at the Hotel Glemmtalerhof in a large north-facing room looking towards the Reiterkogelbahn which could have accommodated 5 people. The hotel is right in the middle of the village with only a short (~200m) walk to either the Reiterkogelbahn taking you onto the south-facing slopes or the Unterschwarzachbahn taking you to the north-facing slopes. Food was fabulous and overall a good hotel. Drawbacks were that is was a bit noisy, since it sat on the middle of the village and there seemed to be an awful lot of smoking being done in the reception, cafe and bar area. Across the valley, right next to the Reiterkogelbahn, was the Hotel Alpine Palace Wolf which looked very posh and maybe worth a go in future.

Some of the other guests were a little odd: Sunday night as Gala dinner night featured a dessert buffet, which they ate from copiously pretty much all the way through the meal. Mrs SomeBeans, qualified to teach food hygiene, observed sufficient prodding and sniffing of the desserts that she preferred not to partake.

Once again we were plagued by “other people”. This time the party who didn’t realise that “Boarding at gate 7” meant: “get on the plane”, and one of whose children spent the flight gently pummelling my back through the seat back – I was calm since I decided to treat it as a free massage!

Overall a very good holiday with some fabulous skiing: this trip was unusual in that we were able to travel in term time – normally we are restricted to school holidays. I suspect the lift system in SkiCircus copes fairly well with February half-term, so might give it a go then next year.

A selection of photos:

|

| This is “twinkly snow”, as you ski past it the ice crystals twinkle. |

|

| Mrs SomeBeans and I on a chairlift, we’re a bit camera shy |

|

| Great snowfields near the top of a mountain |

|

| The Leoganger Steinberge, a panoramic view from Wildenkarkogel |

|

| Looking towards Hinterglemm,invisible over the edge, with pretty clouds and icicles |

|

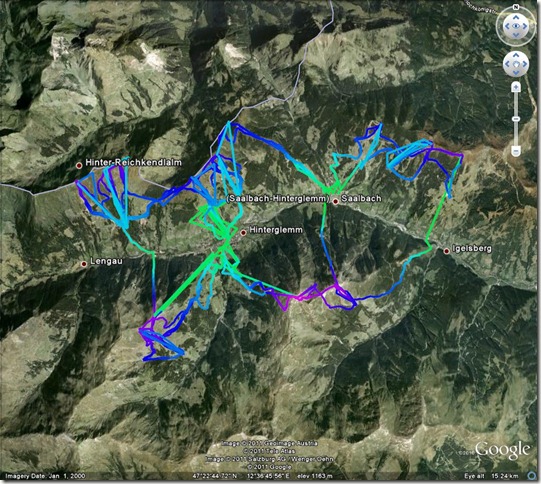

| Obviously I captured GPS data, we covered about 180 miles in 7 days including uplift |

More photos here, along with captions.

Feb 06 2011

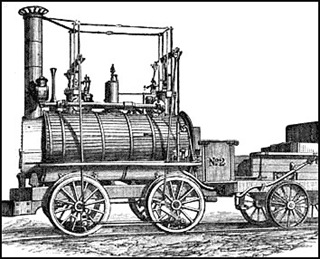

Book review: Lives of the Engineers by Samuel Smiles

Reading the biography of Isambard Kingdom Brunel got me interested in engineers; Rolt, the author of the Brunel biography, mentioned the biographical writings of Samuel Smiles: in particular his “Lives of the Engineers”. This post is about one part of the full work: ”The Locomotive. George and Robert Stephenson” this edition was published in 1879 although the original was written in the years following George Stephenson’s death, around 1860. The title describes its contents. George Stephenson, although not the inventor of the first locomotive, was instrumental in making it a workable proposition and his son (Robert) continued in his fathers line of work, although died quite young.

Reading the biography of Isambard Kingdom Brunel got me interested in engineers; Rolt, the author of the Brunel biography, mentioned the biographical writings of Samuel Smiles: in particular his “Lives of the Engineers”. This post is about one part of the full work: ”The Locomotive. George and Robert Stephenson” this edition was published in 1879 although the original was written in the years following George Stephenson’s death, around 1860. The title describes its contents. George Stephenson, although not the inventor of the first locomotive, was instrumental in making it a workable proposition and his son (Robert) continued in his fathers line of work, although died quite young.

George Stephenson (1781-1848) was born and grew up around Newcastle-upon Tyne, at the time the area was riddled with coal workings. His father was employed as a fireman working on the pumping engine at Wylam colliery.

George is described as an inquisitive child very interested in nature, and constructing models of the machines he saw around him. He started working with the engines at the colliery as a child progressing to ever more responsible jobs at a range of collieries. Alongside this he did various bits of other work, such as shoe-last making and clock and watch repairs to bring more money in; paying to be taught to read and do arithmetic as he entered his late teens. I can’t help making a parallel with Joseph Banks who benefited from a more prosperous upbringing. It’s worth noting here that Samuel Smiles also wrote a book called “Self-help”, it’s clear he’s very much taken with George Stephenson as a self-made man, he is also very much taken with the entirely private nature of the enterprises he undertook.

Steam engines had been used to pump water out of mineworkings since around 1710 with the invention of the steam engine by Thomas Newcomen. These were large, inefficient engines. The first attempts at making a traveling engine seemed to take place around 1769 by Cugnot in France with the first practical moving steam engines due to Richard Trevithick around the turn of the century (1800). In the meantime various miner owners were experimenting with modified roadways to ease the movement of large amounts of heavy stuff (ores, coal) from mine-head to waterway for onward transport. This started with the laying down of wooden roads, followed by metal plates (1738) and finally rails (1776). It’s intriguing to see how the coalescence of these elements around mineworkings led naturally to the invention of the locomotive. For the early railroads, such as the Manchester-Liverpool there was a very real question as to whether locomotives or horses should be used as moving force.

The Manchester-Liverpool line really is key here: it was built out of desperate need for better commercial communication between Liverpool (port) and Manchester (manufacturing centre). In common with many lines there was enormous opposition on the ground from landowners and canal owners. It is also here that the modern locomotive comes into being in the form of the “Rocket”, reliability and commercial viability being absolutely key. In common with Brunel, Stephenson also faced parliamentary committees scrutinising the appropriate railway bill. In early discussions Stephenson argued that the locomotives would not exceed a speed of 12 miles an hour, so as not to scare the parliamentarians. Early railway lines were built with goods in mind, but turned out to be immensely, surprisingly popular for the carrying of passengers. The alternative being slower, less comfortable horse-drawn carriages of much lower capacity. George Stephenson was also responsible for at least some of the initial surveying of routes.

The rate at which the rail network came into being is truly astounding. The Manchester–Liverpool was opened in late 1830 by 1843 there were lines linking London to Birmingham, Southampton, Bristol, Brighton and Dover. There were also lines from Liverpool to Manchester and Leeds and onwards to York and Middlesborough, there was also a line between Newcastle and Carlisle. Follow this there was a wild burst of speculative activity, with several hundred proposals to parliament for new lines in 1845 (maps here).

Also covered in this book is Robert Stephenson (1803-1859), George Stephenson’s son. George gave Robert the education that he wished for himself. Although Robert started his engineering career working in the Stephensons’ locomotive workshop, set up in Newcastle, prior to the building of the Manchester-Liverpool he went on to be involved in the surveying and planning of new railway lines. Most notably bridges such as the Britannia Bridge across the Menai Straits, the Victoria Bridge across the Lawrence Seaway and the High Level Bridge in Newcastle. These first two were both originally “tube” design but were modified in the case of the Victoria bridge to a trestle design and the Britannia bridge was destroyed by fire in 1970. The building of the railways necessitated a huge expansion in bridge building: big, strong, well-built bridges.

Overall an enjoyable read although I suspect Samuel Smiles does not comply with modern historical best practice, with his enthusiasm for self-help, and anecdotes shining through in a number of places. Nevertheless, I feel motivated to read some more of his biographical work of the engineers of the 18th and 19th century.

References

Full text of a number of Samuel Smiles books available here.

Jan 25 2011

Deficit reduction through growth

This blog post seeks to answer the question: what economic growth rate does the UK need to sustain in order to reduce the deficit to zero?

This seems like a relevant question at the moment, and I’ve not seen a straightforward calculation of the answer – so I thought I’d give it a go myself. The idea being that even if the end result is not particularly informative the thinking behind getting the end result is useful.

The key parameter of interest here is the gross domestic product (GDP): the amount of goods and services produced in a year in the UK; it’s a measure of how wealthy we are as a nation, how it increases with time is a measure of economic growth. Also important are the deficit (how much the government’s annual spending exceeds its income) and debt (how much the government is borrowing).

Inflation means that the GDP can appear to grow each year with no increase in real economic activity, therefore I decided to use “inflation adjusted” GDP figures. I also preferred to use annual GDP figures rather than quarterly ones.

To model this I took a starting point of a known GDP, debt, deficit and government spend which I then propagated forwards in time: I made the GDP grow by a fixed percentage each year, and assumed that government spending would be flat (I’m using GDP adjusted for inflation so I think this is reasonable). Assuming that the total tax take is a fixed proportion of GDP I can calculate the deficit and hence increasing debt in each year, I add the debt servicing cost to the government spending in each. Since I’m doing everything else in the absence of inflation I’ve used a debt servicing rate of 2% rather than the 5% implied by a £43bn debt interest cost in 2010 – this makes my numbers a bit inconsistent.

I’ve put the calculation in a spreadsheet here.

Given this model my estimate is that the UK would need to sustain GDP growth of 4.8% per year until 2020 in order to reduce the deficit to 0%. This 4.8% GDP growth brings in approximately an additional £30bn in taxes for each year for which the growth is 4.8%. During this time the debt would rise to nearly 80% of GDP and so the cost of servicing the debt will double. These numbers seem plausible and fit with other numbers I’ve heard knocking around.

To get a feel for how GDP has varied in the past, this is the data for inflation adjusted annual GDP growth in the UK since 1950:

The red line shows the “target” 4.8% GDP growth, and the blue bars the actual growth in the economic, adjusted for inflation. The data comes from here. What’s notable is that GDP growth has rarely hit our target and what’s worse, over the last 40 years there have been four recessions (where GDP growth is negative), so the likelihood must be that another recession before or around 2020 is to be expected.

In real-life we are actually using a combination of GDP, government spending cuts and tax increases to bring down the deficit. These calculations indicate 0.5% GDP growth is approximately £7bn per year which is equivalent to a couple of pence on basic rate (see here) or about 1% of government spending (see here).

Doing this calculation is revealing because it highlights why there is an emphasis on cuts in government spending as a means of reducing the deficit. This had been a bit of a mystery to me with the figure of 80:20 cuts to taxes ratio being widely quoted as some sort of optimum, although there is some indication of other countries working with a ratio closer to 50:50. The thing is that when you cut your spending, you are in control. You can set a target for reduction and have a fair degree of confidence you can hit that target and show you have hit that target relatively quickly and easily. On the contrary relying on growth in GDP, or taxes, is a rather more unpredictable exercise: taxes because the amount of tax raised depends on the GDP.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) published uncertainty bounds for it’s future predictions of GDP in their pre-budget report last year (see p10 and Annex A in this report), their central forecast is for growth of 2.5% but by 2014 (i.e. in only 4 years) they estimated only a 30% chance that it lay between 1.5% and 3.5% actually they only claim a 40% chance of being in that range for this year (2011).

At the risk of being nearly topical, GDP is reported to have shrunk by 0.5% in the last quarter of last year, 2010. This is largely irrelevant to this post, although forecasts for GDP were growth of ~0.5% which supports the idea that GDP is not readily predictable. It’s worth noting that the ONS will revise this figure at monthly intervals until they get all the data in – the current estimate is based on 40% of the data being available.

Given this abysmal ability to predict GDP I suspect that there is little governments can do to influence the growth in GDP. It would be interesting to estimate the influence government policy has relative to prevailing global economic conditions, and what timelags there might be between policy changes and growth.

I think these calculations are illustrative rather than definitive, and what I’d really like is for someone to point to some better calculations!

Jan 22 2011

Which country is the UK like economically?

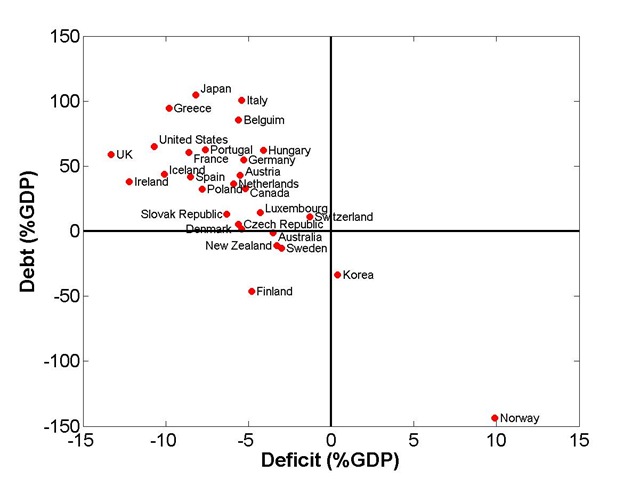

This blog post attempts to answer the economic question: What country is the United Kingdom like economically?

The question arises from discussions of deficit (how much the government’s annual spending exceeds its income) and debt (how much the government is borrowing). To use a digging analogy: debt is a hole, deficit is how fast you are deepening the hole. We can get a feel for how countries compare in this sense by plotting them as a function of their deficits and debts on a graph. I’ve done this for the countries of the OECD (data here). The horizontal axis tells you the deficit, whilst the vertical axis is the debt. These values are plotted as a percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP) so we can compare big countries and small countries, rich countries and poor countries on an equal footing.

As we go to the top left area of this graph we find countries which are in the deepest hole, digging fastest. Out of the extreme left we find the UK – it is digging its hole fastest at the moment, but it is not in the biggest hole – that honour currently goes to Japan. On this graph our nearest neighbours are Ireland, the United States and Iceland, with Greece and Japan having higher debt but lower deficit. France and Spain have similar debts but rather lower deficits.

Norway is actually bringing in more money than it spends and building a surplus, they have large oil revenues and are saving against the day when it runs out. Korea is doing this too but to a far smaller extent.

Economically it is often said that the PIGS or PIIGS countries are in most trouble in Europe, these are Portugal, Ireland, (Italy), Greece and Spain.

But is it true to say we are like Ireland, the US and Iceland? Ireland and Greece have much higher levels of unemployment than us, whilst the US has slightly higher levels and Iceland’s levels are comparable. Iceland has very high inflation (12%) whilst most other countries have moderate inflation including the UK, with a few countries having moderate deflation including the US and Ireland. We have moderate levels of unemployment, with Ireland, Greece, the US having much higher levels. It’s also worth pointing out that the UK has a population of 60,000,000 whilst Ireland only has 4,000,000 and Iceland a mere 300,000.

So whilst in deficit/debt terms we may resemble other countries in other, economically relevant ways, we are quite different.

From a mathematical point of view there are methods for measuring the closeness of things based on large numbers of variables, called clustering algorithms. These algorithms amount to our eyeballing of the debt/deficit data – they are a measure of distance. However, in economic problems things aren’t so simple. The economy is described by many variables and I don’t know their relative importance in determining economic similarity. The problem that the numbers involved may vary tremendously in size is trivially solved. My suspicion is that economists have probably spent a great deal of time arguing about economic similarity and haven’t come to a definitive answer.

So in answer to the question: What country is the United Kingdom like economically? Although the UK may be most like Ireland, the US and Iceland in debt/deficit terms. In terms of many other economic factors such as inflation, unemployment and so forth it is quite different. I suspect the real answer to this question is that the UK is most like France, Germany and Italy economically: these countries are of similar size, have similar unemployment rates, have inflation of the same sign, usually run public sector/ private sector ratios of similar size furthermore given their common membership of the EU their economic behaviour is probably similar. Of this group of countries Italy has the largest debt and we have a largest deficit.

Jan 13 2011

Book Review: The Third Man by Peter Mandelson

A little bit of politics for this book review: “The Third Man: Life at the heart of New Labour” by Peter Mandelson. It’s been a while since I’ve read much politics; I did go through a spell of reading various diaries and biographies (Alan Clark, Tony Benn, John Major, Churchill) a number of years ago but gave up largely because the diarists and autobiographies seemed unwilling to accept they were wrong on anything, and I had a nasty experience with the biography of Gladstone.

A little bit of politics for this book review: “The Third Man: Life at the heart of New Labour” by Peter Mandelson. It’s been a while since I’ve read much politics; I did go through a spell of reading various diaries and biographies (Alan Clark, Tony Benn, John Major, Churchill) a number of years ago but gave up largely because the diarists and autobiographies seemed unwilling to accept they were wrong on anything, and I had a nasty experience with the biography of Gladstone.

I’m sort of fond of Peter Mandelson, I never really bought the Prince of the Dark Arts thing and he seems to be one of the more coalition minded senior Labour figures.

The book covers briefly Mandelson’s early life but the main focus of the book is the personal relationship between Tony Blair, Peter Mandelson and Gordon Brown from the late eighties all the way through to the 2010 election. Peripherally it is also the story of New Labour: firstly, a switch to a more professional presentational style, followed by the scrapping of Clause IV then it seems to go a bit vague in terms of a guiding policy theme. Mandelson states the central vision of New Labour being of fairness and social justice: but these are ideals I’m sure the Liberal Democrats would cleave to and the Tories would claim the same. Ultimately ideology is not helpful in discriminating between parties rather implementation of policy and no-one is really grasping the nettle of going for excellent implementation.

I’d always assumed that poor press for Labour ministers was as a result of biased media and some mysterious influence from the Tories that I hadn’t entirely thought through. Mandelson makes it pretty clear that the worst press for Labour came from Labour ministers and their hangers-on briefing against each other!

The central theme of the book was how awful the relationship between Brown and Blair was, lasting for many years and seriously hampering a New Labour programme for reform. The origin of this poor relationship is in the leadership struggle which took place following the death of John Smith in 1994. Communication between the Prime Minister and the Chancellor was poor, and they often seemed to be working largely to block each other. This makes hard reading, it’s like the story of a couple trapped in a loveless marriage “for the sake of the kids”. In some ways I find this disturbing: New Labour effectively provided it’s own opposition whilst in government in the sense that it limited their ability to make policy and enforce change on public services. What happens when the Prime Minister and the Chancellor are working to the same agenda?

Clearly as a Liberal Democrat I’m interested in what he has to say about us, the truth is: not much. There seems to be a degree to which Mandelson and Blair held key early members such as Roy Jenkins in high regard, seeing them as something of a lost tribe who had left the Labour party in the early eighties believing it to be un-reformable. He also describes the talk toward involving the Liberal Democrats in government following the 1997 election, eventually floundering because ultimately there was no need to give anything to the Liberal Democrats. It does seem that there was some quiet local arrangements where Labour or Liberal Democrats agreed not to fight too hard against each other at general elections. I suspect things have changed in both parties now, Liberal Democrats and Labour members of my generation and younger joined well after the split so for us the “progressive alliance” is something of an old man’s tale.

What also comes through for me is how grateful Labour should be for our electoral system, in the 1983 election when Labour polled 27.6% and the SDP-Alliance polled 25.4% they still gained 209 seats as opposed to the meagre 23 that the SDP-Alliance achieved. Similarly at the 2010 election, the Conservatives lead Labour by 7.1% in votes but only 48 seats whilst in 2005 Labour led Tory by just 2.8% but gained a 157 seat lead over the Conservatives giving them a firm majority.

Mandelson’s description of the Coalition negotiations following the May 2010 General Election are consistent with the Laws and Wilson books which I reviewed previously. Labour had not made any pre-election plans for coalition, which I still find odd since Peter Mandelson clearly saw the possibility of a hung parliament; the Labour party was split on whether they should make the attempt and ultimately there was a recognition that the parliamentary arithmetic did not add up.

It’s clear that the current theme of “no cuts” from Labour is a continuation of the Brown policy pre-election, Alastair Darling appears to have made considerable efforts to reach a budget which made at least some effort to start addressing the deficit in the final days of the previous government, in the teeth of enormous opposition from Gordon Brown whilst other members of the team such as Ed Balls were keen to make further spending commitments. Brown’s great fear seemed to have been being labelled a “tax-and-spend” Chancellor, who seems to have ended up a “spend” Chancellor and in the long term that does not add up.

Is this a good book to read? It is if you want to know about the personal relationship at the core of the book, and if want to know more about Peter Mandelson. I’m tempted to read Andrew Rawnsley’s “The End of the Party” for a more detached view.