“Map of a Nation” by Rachel Hewitt is the story of the Ordnance Survey from its conception following the Jacobite Uprising in Scotland in 1745 to the completion of the First Series maps in 1870. As such it interlinks heavily with previous posts I have made concerning the French meridian survey, Maskelyne’s measurements of the weight of the earth at Schiehallion, Joseph Banks at the Royal Society, William Smith’s geological map of Britain and Gerard Mercator.

“Map of a Nation” by Rachel Hewitt is the story of the Ordnance Survey from its conception following the Jacobite Uprising in Scotland in 1745 to the completion of the First Series maps in 1870. As such it interlinks heavily with previous posts I have made concerning the French meridian survey, Maskelyne’s measurements of the weight of the earth at Schiehallion, Joseph Banks at the Royal Society, William Smith’s geological map of Britain and Gerard Mercator.

The core of the Ordnance Survey’s work was the Triangulation Survey, the construction of a set of triangles across the landscape made by observing the angles between landmarks (or triangulation points) ultimately converted to distances. This process had been invented in the 16th century, however it had been slow to catch on since it was slow and required specialist equipment and knowledge. Chromatic abberration in telescopes was also a factor – if your target is surrounded with multi-colour shadows – which one do you pick to measure? The triangles are large, up to tens of miles along a side, so within these triangles the Interior Survey was made which details the actual features on the ground – tied down by the overarching Triangulation Survey.

A second component of this survey is the baseline measurement – a precise measurement of the length of one side of one triangle made, to put it crudely, by placing rulers end to end over a straight between the terminal triangulation points.

The Triangulation Survey is in contrast to “route” or “transverse” surveys which measure distances along roads by means of a surveyor’s wheel, note significant points along the roadside. There is scope for errors in location to propagate. Some idea of the problem can be gained from this 1734 map showing an overlay of six “pre-triangulation” maps of Scotland, the coastline is all over the place – with discrepancies of 20 miles or so in places.

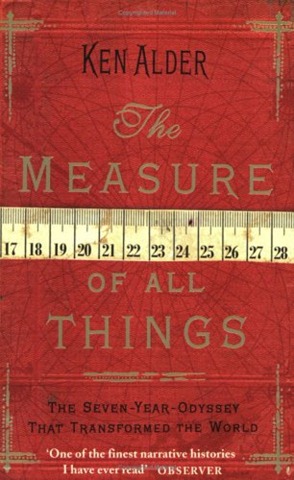

The motivation for the Ordnance Survey mapping is complex. Its origins were with David Watson in the poorly mapped Scotland of the early part of the 18th century, and the Board of Ordnance – a branch of the military concerned with logistics. There was also a degree of competition with the French, who had completed their triangulation survey for the Carte de Cassini and were in the process of conducting the meridian survey to define the metre. The survey of England and Wales was completed after the Irish Triangulation and after the Great Trigonometric Survey of India – both the result of more pressing military and administrative needs. As the survey developed in England more and more uses were found for it. Indeed late in the process the Poor Law Commission were demanding maps of even higher resolution than those the Ordnance Survey initially proved, in order to provide better sanitation in cities.

The Survey captured popular imagination, the measurements of the baseline at Hounslow Heath were a popular attraction. This quantitative surveying was also in the spirit of the Enlightenment. There was significant involvement of the Royal Society via its president, Joseph Banks, and reports on progress were regularly published through the Society. Over the years after the foundation of the Ordnance Survey in 1791 accurate surveying for canals and railways was to become very important. In the period before the founding of the Ordnance Survey surveying was a skill, related to mathematics, which a gentleman was supposed to possess and perhaps apply to establishing the contents of his estate.

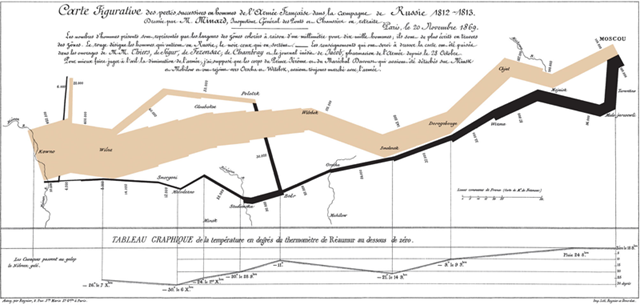

Borda’s repeating circle, used in the French meridian survey to measure angles, found its counterpart in Jesse Ramsden’s “Great Theodolite“, a delicate instrument 3 feet across and weighing 200lbs. The interaction with the French through the surveying of Britain is intriguing. Prior to the French Revolution a joint triangulation survey had been conducted to establish exactly the distance between the Paris and Greenwich meridians, with the two instruments pitted against each other. There was only a 7 foot discrepancy in the 26 miles the two teams measured by triangulation between Dover and Calais. In 1817, less than two years after the Battle of Waterloo a Frenchman, Jean-Baptiste Biot, was in the Shetlands with an English survey team extending the meridian measurements in the United Kingdom.

The accuracy achieved in the survey was impressive, only one baseline measurement is absolutely required to convert the angular distances in the triangulation survey into distances but typically other baselines are measured as a check. The primary baseline for the Triangulation Survey was measured at Hounslow Heath, a second baseline measured at Romney Marsh showed a discrepancy of only 4.5 inches in 28532.92 feet, a further baseline measured at Lough Foyle, in Northern Ireland found a discrepancy of less than 5 inches in 41,640.8873 feet.

The leaders of the Ordnance Survey were somewhat prone to distraction by the terrain they surveyed across, William Roy, for example, wrote on the Roman antiquities of Scotland. Whilst Thomas Colby started on a rather large survey of the life and history of Ireland. Alongside these real distractions were the more practical problems of the naming of places: toponymy, particularly difficult in Wales and Ireland where the surveyors did not share the language of the natives.

Overall a fine book containing a blend of the characters involved in the process, the context of the time, the technical details and an obvious passion for maps.

Footnotes

In writing this blog post I came across some interesting resources:

- Computer generated panoramas, found following comments on the view from Black Combe in the Lake District

- Online reproductions of the First Series (1870), Popular Edition (1919-26) and New Popular Editions (1945-47) of the Ordnance survey Maps. Zoom to the appropriate level and Bing Maps will reveal the Ordnance Survey 1:50,000 map.

- The Charles Close Society, dedicated to the study of Ordnance Survey maps.